The Myths Of Graphics Card Performance: Debunked, Part 1

Did you know that Windows 8 can gobble as much as 25% of your graphics memory? That your graphics card slows down as it gets warmer? That you react quicker to PC sounds than images? That overclocking your card may not really work? Prepare to be surprised!

Performance That Matters: Going Beyond A Graphics Card's Lap Time

If you're an auto enthusiast, you've no doubt debated the performance of two sports cars with a friend at some point. One might have made more horsepower. Maybe it had a higher top speed, superior handling, or lighter weight. Typically, those conversations come down to comparing lap times on the Nürburgring and end when someone spoils the fun by reminding us that we can't afford any of the contenders anyway.

In many ways, high-end graphics cards can be quite similar. You have average frame rate, frame time variance, noise from the cooling solution, and a range of price points, which can incidentally double the cost of a current-gen gaming console. And if you needed any further convincing, some of the latest video cards have aluminum and magnesium alloy frames, just like race cars. Alas, some differences remain. Despite my best attempts at impressing my wife with the latest graphics processor, she remains impervious.

So, what is the lap time equivalent for a video card? What is the one measure that distinguishes winners from losers, cost being equal? It's clearly not just average frames per second, as demonstrated by all of the coverage we've given to frame time variance, tearing, stuttering, and fans that sound like jet engines. Then you get into the more technical specifications: texture fill rate, compute performance, memory bandwidth. What significance do all of those numbers hold? And, like a Formula 1 pit crew member, does your new card require headphones just to be tolerated? How do you account for the overclocking headroom of each card in an evaluation?

Before we dig into the myths that envelop modern graphics cards, let's start by defining what performance is and what it is not.

Performance Is An Envelope, Not One Number

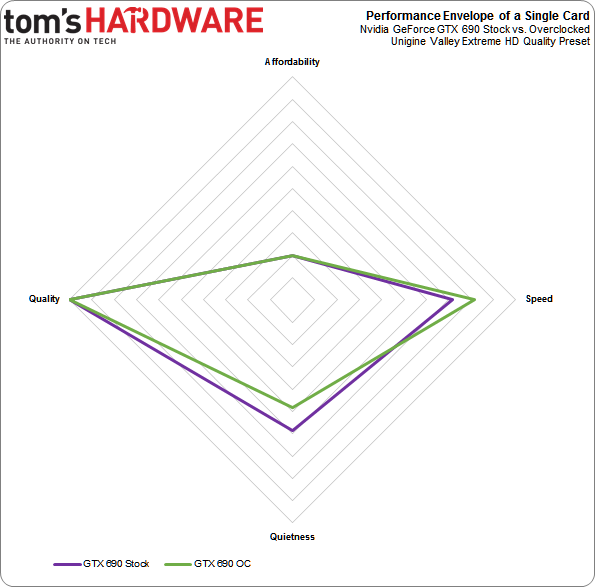

Discussions of GPU performance are often distilled down to generalizations based on FPS, or average frames per second. In reality, a graphics card's performance includes far more than the rate at which it renders frames. It's better to think in terms of an envelope, rather than one data point, though. This envelope has four major dimensions: speed (frame rate, frame latency, and input lag), quality (resolution and image quality), quietness (acoustic performance, driven by power consumption and cooler design), and of course affordability.

Other factors play into a card's value, such as game bundles and vendor-specific technologies. I'll cover them briefly, but won't try to weigh them quantitatively. Truly, the importance of CUDA, Mantle, and ShadowPlay support is very user-dependent.

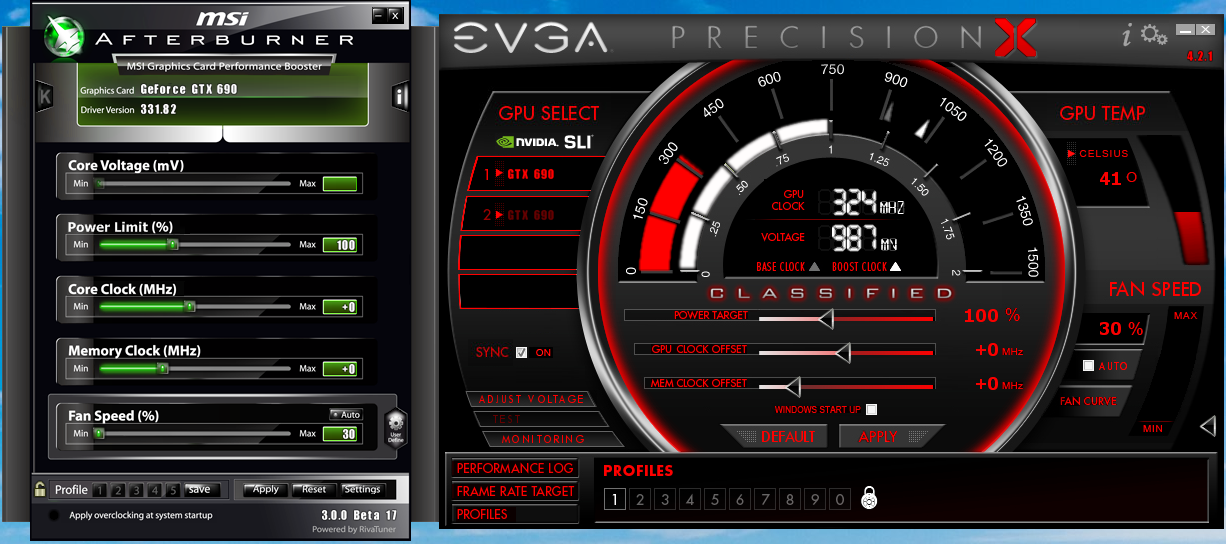

The above graph illustrates the GeForce GTX 690's position in this variable envelope I'm describing. Stock, it achieves 71.5 FPS using a test system I'll detail on the following page in Unigine Valley 1.0 at the ExtremeHD preset. It generates an audible, but not bothersome 42.5 dB(A). If you're willing to live with a borderline-noisy 45.5 dB(A), you can easily overclock the card and get a stable 81.5 FPS using the same preset. Lower the resolution or anti-aliasing level (affecting quality), and you get a big bump up in frame rate, all else being equal. Of course, the (un)affordable $1000 price point doesn't change.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

For the sake of running tests in a more controlled manner than you're used to seeing, let's define a reference for video card performance.

For the purposes of today's story, I'll specify performance as the frames per second a graphics board can output at a given resolution, within a specific application along the described envelope (and under the following conditions):

- Quality settings in a given application set to their highest value (typically the Ultra or Extreme preset)

- Resolution set to a constant level (typically 1920x1080, 2560x1440, 3840x2160, or 5760x1080 in a three-monitor array)

- Driver settings at each manufacturer's defaults (whether global or application-specific)

- Operating in a closed enclosure at a set 40 dB(A) noise level measured three feet away from the enclosure (ideally, tested on a reference platform that gets updated annually)

- Operating with an ambient temperature of 20 °C/68 °F and one atmosphere air pressure (this is important; it directly affects thermal throttling)

- Core and memory operating at temperature equilibrium as far as thermal throttling is concerned (so that core/memory clock speeds under load remain fixed or vary within a tight range, given a constant 40 dB(A) noise level (and corresponding fan speed) target

- Maintaining a 95th percentile frame time variance below 8 ms, which is half a frame at a typical display refresh rate of 60 Hz

- Operating at or near 100% of GPU utilization (this is important to demonstrate a lack of platform bottlenecks; if there are bottlenecks, GPU utilization will be below 100% and the test results will not be very meaningful)

- Averaged FPS and frame time variance data from no fewer than three runs per data point, each run no less than one minute long, with individual samples exhibiting no more than 5% deviation from the mean(ideally we want to sample different cards of the same time, particularly when there is reason to believe a vendor's products exhibit significant variance)

- Measured with either Fraps for a single card or any built-in frame counter; FCAT is required for multiple cards in SLI/CrossFire

As you can imagine, the reference performance level is both application- and resolution-dependent. But it's defined in a way that allows for independent repetition and verification of tests. In this sense, it's a truly scientific approach. As a matter of fact, we encourage the industry and enthusiasts alike to repeat the tests we perform and bring any discrepancies to our attention. Only in this way will the integrity of our work be assured.

This definition of reference performance does not account for overclocking, or the range of behaviors a given GPU might exhibit from one card to another. Fortunately, we'll see that's only an issue in a few cases. Modern thermal throttling mechanisms are designed to eke out maximum frame rates in as many situations as possible, so cards are operating closer than ever to their limits. Ceilings are often hit before overclocking adds any real-world benefit.

Unigine Valley 1.0 is a benchmark we use extensively in this article. It features a number of DirectX 11-based features and produces highly repeatable tests. It also doesn't rely on physics (and thus CPU) as much as 3DMark (at least in its overall and combined tests).

What Are We Setting Out To Do Here?

In the course of this two-part story, I plan to look at each of the dimensions that compose a video card's performance envelope, and then try to answer common questions about them. We'll extend the conversation to input lag, display ghosting, and tearing, all of which relate to your gaming experience, but not specifically to frame rates. I'd also like to compare cards using this criteria. As you can imagine, testing this way is extremely time consuming. However, I think the additional insight is worth the effort. That doesn't mean our graphics card reviews are going to change; we're experimenting, and taking you with us.

With the definition of graphics card performance already covered, the rest of today's piece involves methodology, V-sync, noise and the noise level-adjusted performance of graphics cards, and a look at the amount of video memory you really need. Part two will look at anti-aliasing technologies, the impact of display choice, various PCI Express link configurations, and the idea of value for your money.

Time to move on to the test system setup. More so here than in other reviews, you will want to read that page carefully, since it contains important information about the tests themselves.

Current page: Performance That Matters: Going Beyond A Graphics Card's Lap Time

Next Page Graphics Card Myth Busting: How We Tested-

manwell999 The info on V-Sync causing frame rate halving is out of date by about a decade. With multithreading the game can work on the next frame while the previous frame is waiting for V-Sync. Just look at BF3 with V-Sync on you get a continous range of FPS under 60 not just integer multiples. DirectX doesn't support triple buffering.Reply -

hansrotec with over clocking are you going to cover water cooling? it would seem disingenuous to dismiss overclocking based on a generating of cards designed to run up to maybe a speed if there is headroom and not include watercooling which reduces noise and temperature . my 7970 (pre ghz editon) is a whole different card water cooled vs air cooled. 1150 mhz without having to mess with the voltage on water with temps in 50c without the fans or pumps ever kicking up, where as on air that would be in the upper 70s lower 80s and really loud. on top of that tweeking memory incorrectly can lower frame rateReply -

hansrotec I thought my last comment might have seemed to negative, and i did not mean it in that light. I did enjoy the read, and look forward to more!Reply -

hansrotec I thought my last comment might have seemed to negative, and i did not mean it in that light. I did enjoy the read, and look forward to more!Reply -

noobzilla771 Nice article! I would like to know more about overclocking, specifically core clock and memory clock ratio. Does it matter to keep a certain ratio between the two or can I overclock either as much as I want? Thanks!Reply -

chimera201 I can never win over input latency no matter what hardware i buy because of my shitty ISPReply -

immanuel_aj I'd just like to mention that the dB(A) scale is attempting to correct for perceived human hearing. While it is true that 20 dB is 10 times louder than 10 dB, but because of the way our ears work, it would seem that it is only twice as loud. At least, that's the way the A-weighting is supposed to work. Apparently there are a few kinks...Reply