Radeon HD 6970 And 6950 Review: Is Cayman A Gator Or A Crock?

Last month, Nvidia launched its GeForce GTX 580, but we told you to hold off on buying it. A week ago, Nvidia launched GeForce GTX 570 and we again said "wait." AMD's Cayman was our impetus. Were Radeon HD 6970 and 6950 worth the wait? Read on for more!

AMD Acknowledges That Geometry Matters

When Nvidia first briefed us on the gaming-oriented features of its Fermi architecture almost a year ago, it put the emphasis squarely on geometry. The company argued that modern GPUs have tons of shader performance—and we’d agree. For a flagship graphics card, we have to apply resolutions that most folks can’t even support and multiple monitor arrays just to tax performance. We aren't looking at photorealistic representations of our opponents' lower intestines in Call of Duty yet, but we’re certainly getting there.

Unfortunately, the number of triangles per scene has not kept up. A mountain landscape might be peppered with very real-looking trees and grasses blowing in the wind, but the contours of the environment itself are distinctly geometric—not natural at all. The company purported to solve that issue with its PolyMorph engine—a tessellation unit in each Shader Multiprocessor that’d facilitate scalable performance when software developers started exploiting DirectX 11’s ability to dial up the geometric complexity of a scene.

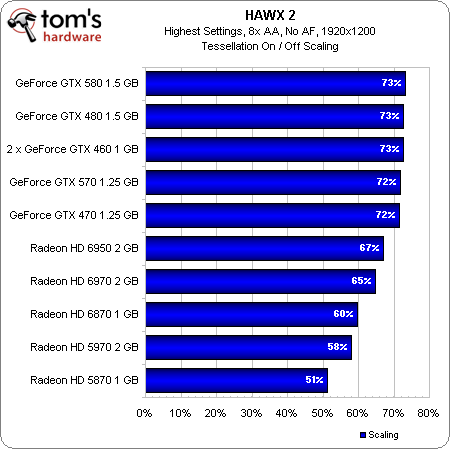

At the time, AMD responded that its own tessellation engine was more than capable of competing with Nvidia’s parallelized implementation. At the time, Unigine’s Heaven benchmark proved that to not be the case. Later, HAWX 2 gave us a real-world example of Nvidia’s architecture scaling better (though not as well as we might have expected, given Nvidia's insistence on the unit's scalability).

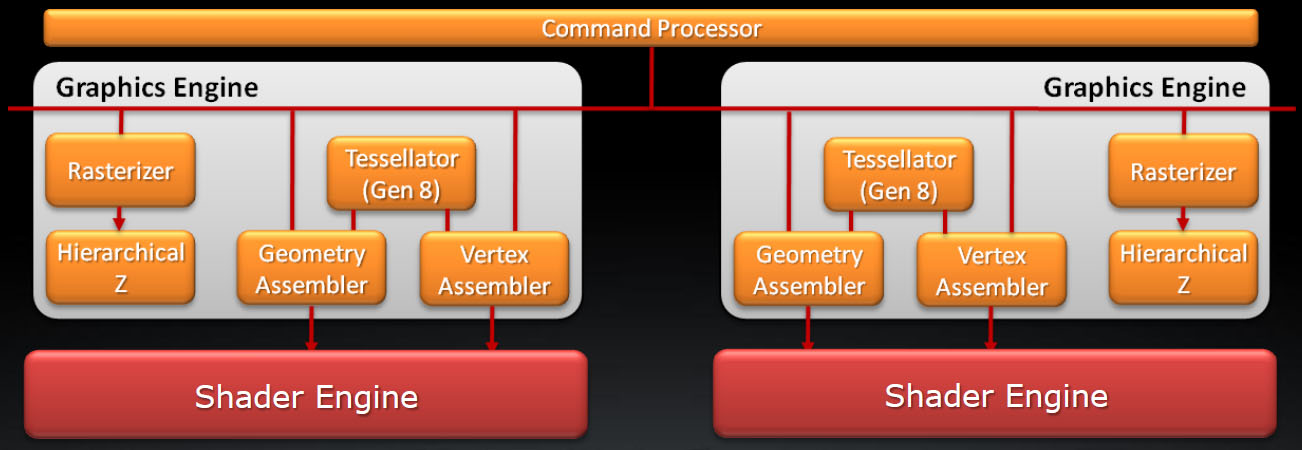

With its Radeon HD 6900-series, AMD attempts to bridge the gap with a more focused stab at geometry. When we first looked at the Radeon HD 5870 more than a year ago, we observed that what AMD called dual rasterizers in its graphics engine was actually a rasterizer with a twice as many scan conversion units, upping the pixel throughput to 32 per clock. Now, with the 6900-series’ Cayman processor, you’re still looking at 32 pixels per clock from the rasterizer hardware. However, AMD essentially duplicated its geometry block in the new architecture (handling transform, setup, backface culling, and tessellation subdivision) adding a bit of load-balancing hardware to help with scaling. At the end of the day, Cayman can handle two triangles per clock, where Cypress (5800 series) and Barts (6800 series) could do one. Additionally, should Cayman’s on-chip caches overflow, as can happen when you’re talking about the extreme number of triangles associated with high tessellation factors, the additional vertices spill over to the frame buffer.

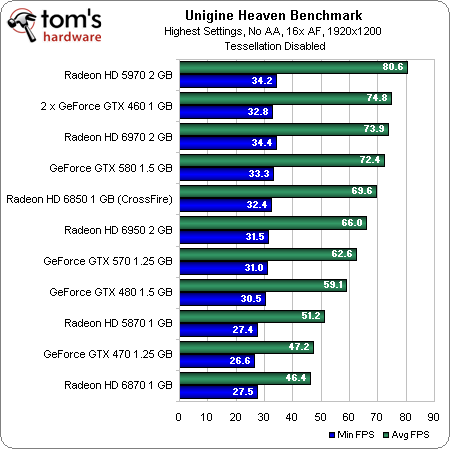

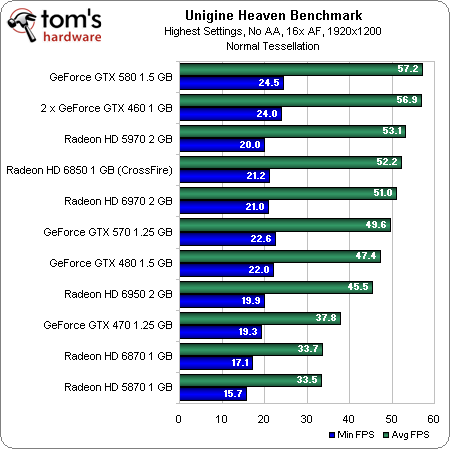

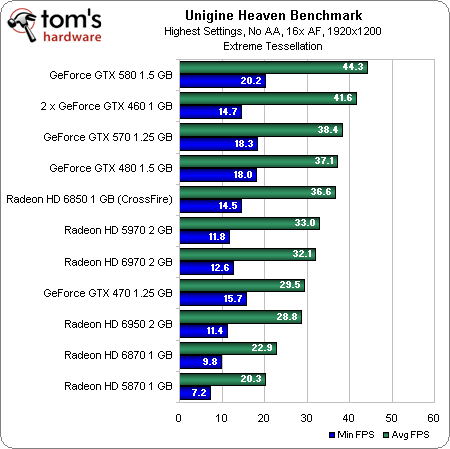

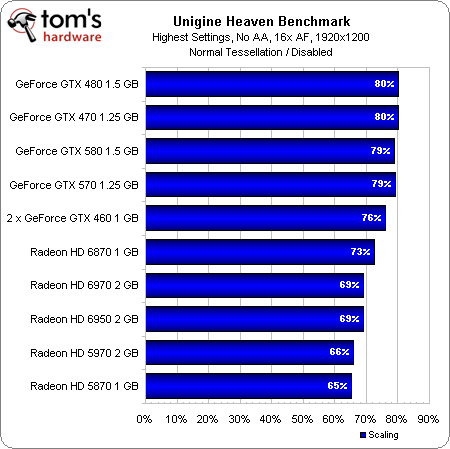

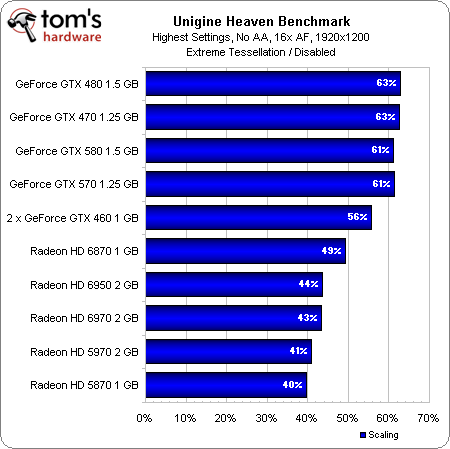

How does this translate into actual performance? Well, let’s start by running these cards through the same synthetic Unigine tests we’ve used in past reviews:

You can see the new cards do well with tessellation turned off—the 6970 even trumps Nvidia’s GeForce GTX 580. Increasing the tessellation factor hits the AMD boards incrementally harder, though, putting us in the eventual position where a GeForce GTX 480 outmaneuvers two 6850s in CrossFire.

Get past the raw frame rates, though, and we can see that, while the Radeon HD 6900-series boards scale better than the 5800-series cards, improvements made to the Radeon HD 6800s seem to make more of a difference, as the Radeon HD 6870 tops the chart for AMD. Unfortunately for Cayman, that means Nvidia’s approach still yields a better scaling story.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

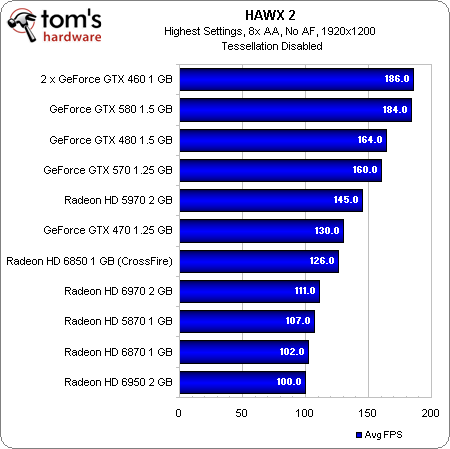

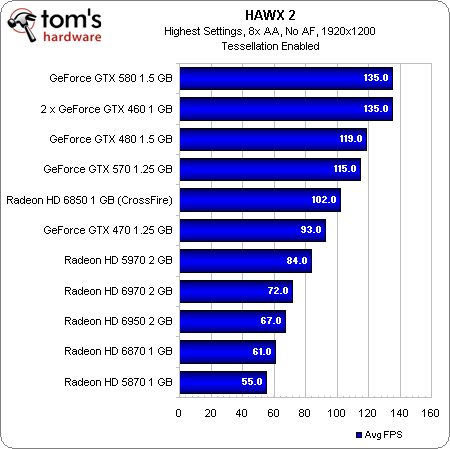

The performance in HAWX 2—really the only shipping game that uses tessellation to improve realism—isn’t much better for the 6900-series cards. The Radeon HD 6970 and 6950 bring up the bottom of the range behind cards like the GeForce GTX 570 and 470.

Check out the scaling chart, though. The Radeon HD 6970, despite losing out to all of Nvidia’s competing cards, comes a lot closer to matching the competition’s scaling profile here, and the Radeon HD 6950 does even better.

It’s interesting that none of Nvidia’s GeForce boards scale based on the number of available PolyMorph engines. They all get stuck around 73% of their performance with tessellation turned on. This is almost assuredly what enables AMD’s cards to “catch up.”

Current page: AMD Acknowledges That Geometry Matters

Prev Page Building Cayman By Improving Cypress Next Page Adding Value Through Anti-Aliasing, Eyefinity, And Video-

Annisman Thanks for the review Angelini, these new naming schemes are hurting my head, sometimes the only way to tell (at a quick glance) which AMD card matches up to what Nvidia card, is by comparing the prices, which I think is bad for the average consumer.Reply -

rohitbaran These cards are to GTX 500 series what 4000 series was to GTX 200. Not the fastest at their time but offer killer performance and feature set for the price. I too expected 6900 to be close to GTX 580, but it didn't turn out that way. Still, it is the card I have waited for to upgrade. Right in my budget.Reply -

notty22 AMD's top card is about a draw with the gtx 570.Reply

Pricing is in line.

Gives AMD only hold outs buying options, Nvidia already offered

Merry Christmas -

IzzyCraft Sorry all i read was thisReply

"This helps catch AMD up to Nvidia. However, Intel has something waiting in the wings that’ll take both graphics companies by surprise. In a couple of weeks, we'll be able to tell you more." and now i'm fixated to weather or not intel's gpu's can actually commit to proper playback. -

andrewcutter but from what i read at hardocp, though it is priced alongside the 570, 6970 was benched against the 580 and they were trading blows... So toms has it at par with 570 but hard has it on par with 580.. now im confused because if it can give 580 perfomance or almost 580 performance at 570 price and power then this one is a winner. Sim a 6950 was trading blows with 570 there. So i am very confusedReply -

sgt bombulous This is hilarious... How long ago was it that there were ATI fanboys blabbering "The 6970 is gonna be 80% faster than the GTX 580!!!". And then reality hit...Reply