Video Transcoding Examined: AMD, Intel, And Nvidia In-Depth

Intel, AMD, And Nvidia: Decode And Encode Support

Decode Support: A History Of Formats

There is a caveat with video decoded in hardware. Not every solution exposes the same degree of processing.

For Intel, motion compensation was the only hardware-accelerated stage of the video pipeline for several generations of graphics products (GMA 900, 850, 3000, and 3100). That meant that you used a software decoder to uncompress the video bitstream before Intel's logic circuits performed motion compensation. It wasn't until a later revision of 3100 that we actually saw full hardware-based decoding of MPEG-2. Support for VC-1 and H.264 didn't come until the 4500MHD. Remember that GMA 500 doesn't count since Imagination Technologies developed it for Intel.

Meanwhile, AMD recently released UVD 3 with its Radeon HD 6000-series. Originally, UVD 1 supported full VC-1 and H.264 decoding. UVD 2 added frequency transformation and motion compensation to MPEG-2. UVD 3 adds full decoding support for MVC, MPEG-2, and MPEG-4/DivX/Xvid. Note that UVD on AMD's 5000-series cards underwent a firmware-level revision. There was enough of a hardware change that AMD added dual-stream decoding support. The Radeon HD 4000-series already had picture-in-picture and dual-stream decoding support, but this was limited to SD resolutions.

Nvidia started out with MPEG-1/MPEG-2 hardware-based decoding on its GeForce FX. The first generation of PureVideo emerged when Nvidia took that hardware, improved deinterlacing and overlay resizing, and built it onto the GeForce 6000-series. For the most part, decoding acceleration was limited, as it excluded frequency transformation, initial run and variable length decoding. H.264 hardware decoding didn't crop up until GeForce 6600. Today, we are up to the fourth generation of PureVideo, which adds MPEG-4 (Advanced) Simple Profile bitstream decoding, along with MVC for 3D Blu-ray content.

Encode Support

Up until Quick Sync, there was no such thing as a fixed-function encoder (for desktop PCs). Nearly all encoding was achieved on the software side using pure CPU horsepower. If you had a fast computer, you could encode faster. It was as simple as that. And, if you remember far enough back, there was a time when software-based encoding was only done on a single thread, severely limiting performance. Times have changed, and the process can largely be parallelized.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

For the most part, we are still dealing with software-based encoders. The only difference is that now we have encoders that can do all of the work in the GPU by way of GPGPU programming libraries. And while we’ve all been trained to think that general-purpose GPU computing is the future, at least relative to the more limited parallelism offered by a CPU, the tasks we’re talking about here simply cannot run as quickly or as efficiently (power-wise) in general-purpose logic circuit. So, now we end up comparing GPGPU-based encoders that operate using hardware that lives on a graphics card to Intel's mixed fixed-function/general purpose implementation.

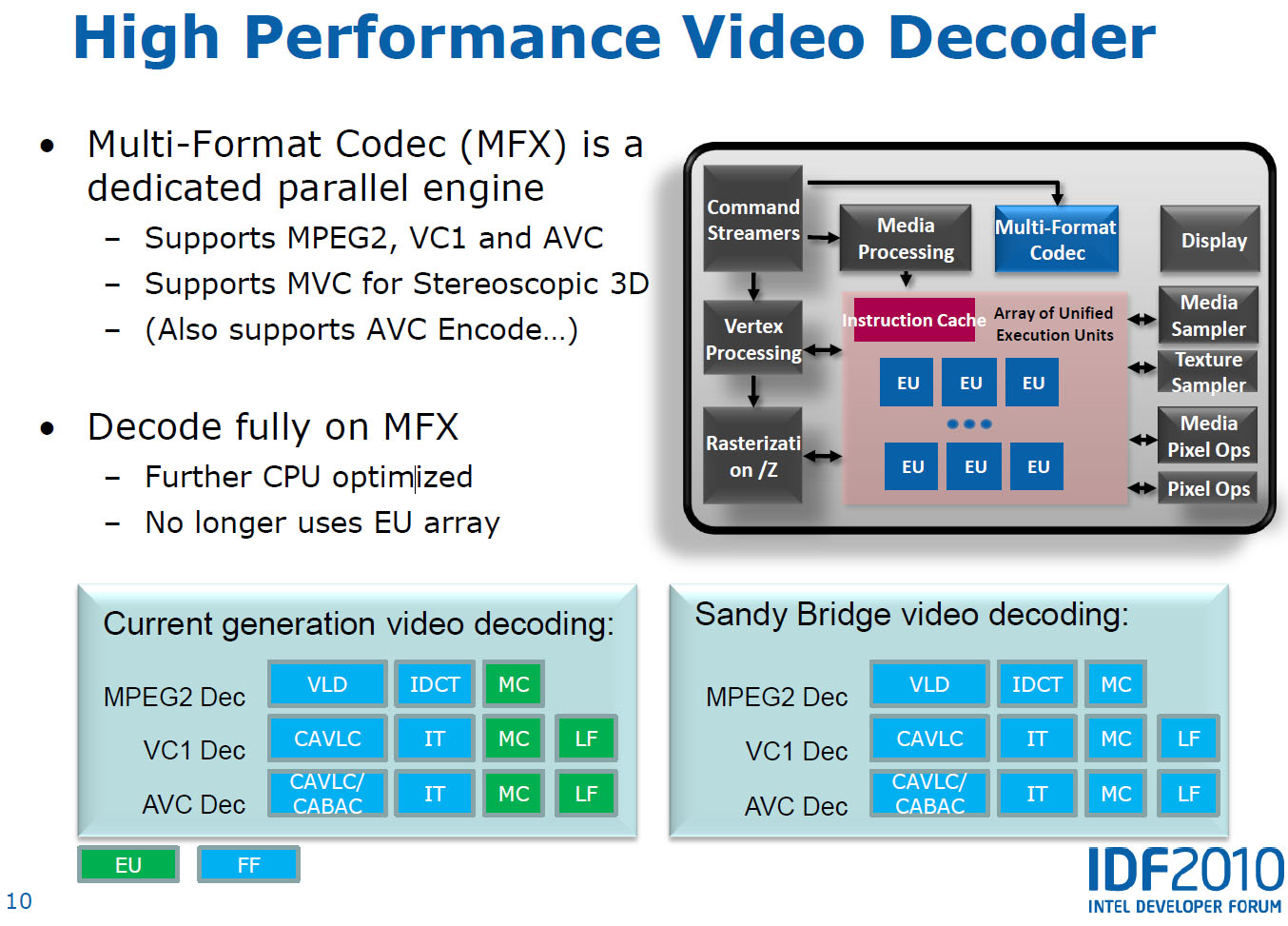

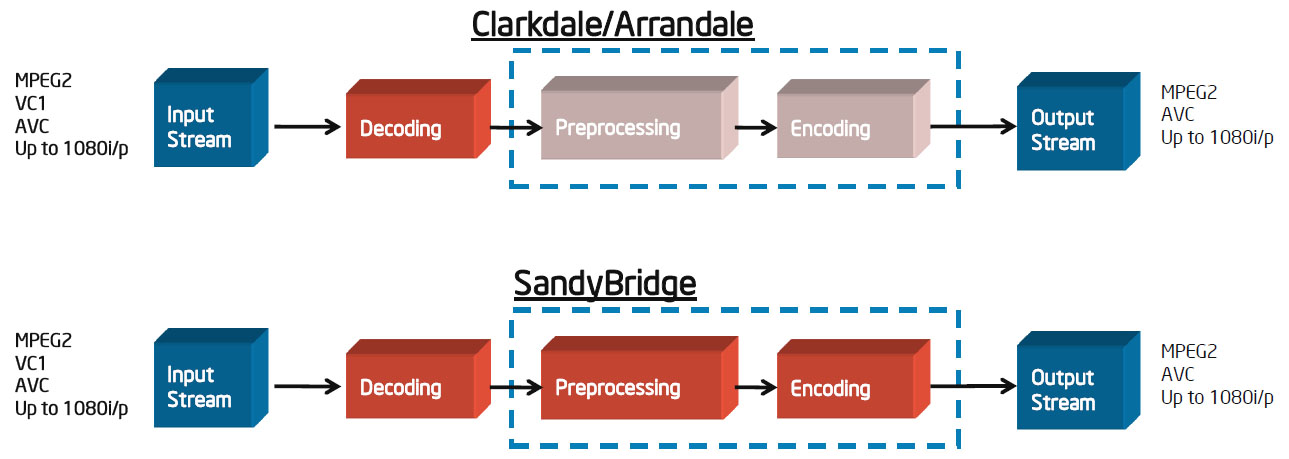

On the encode side, you have fixed-function logic working in concert with the programmable execution units. There’s a media sampler block attached to the EUs (Intel calls this a co-processor) that handles motion estimation, augmenting the programmable logic. Of course, the decoding tasks that happen during a transcode travel down the same fixed-function pipeline already discussed, so there’s additional performance gained there. Feed in MPEG-2, VC-1, or AVC, and you get MPEG-2 or AVC output from the other side.

Depending on the application in question, the way each company employs Quick Sync is naturally going to be different. Take CyberLink, for example. PowerDVD 10 capitalizes on the pipeline’s decode acceleration. A MediaEspresso project is going to be significantly more involved—it’ll read the file in, decode, encode, and turn back the output stream. Then, in PowerDirector, a video editing app, you have to factor in post-processing—the effects and compositing that happens before everything gets fed into the encode stage.

Optimizing for Transcoding

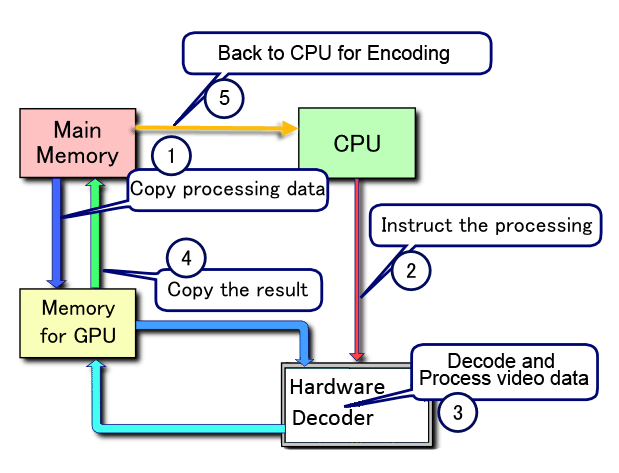

The transcode pipeline involves reading a file in, decoding it, encoding it, and outputting it. Before the development of GPGPU-based encoding, transcoding software used the CPU to copy data from video memory (where it resided after hardware-accelerated decoding) and sent it back to system memory, where the CPU was able to perform the encode stage.

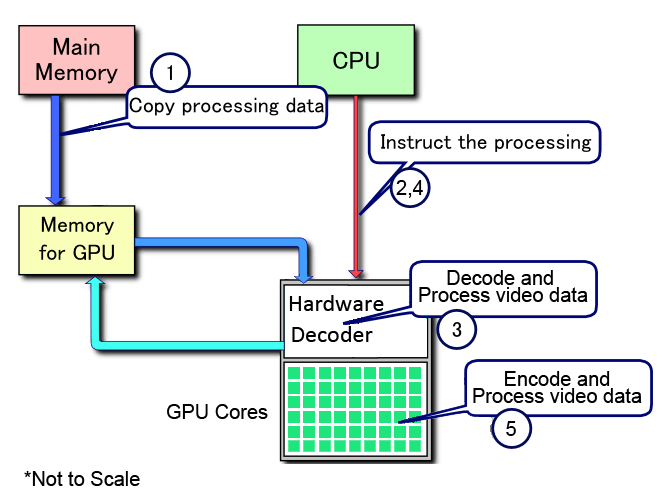

Because the fixed-function decoder is on the same piece of silicon as a GPU, the software can skip copying the data back to system memory (step four in the first diagram). General-purpose GPU-based transcoding allows almost the entire process to happen on one piece of silicon. These are performance-oriented considerations, though, and our focus today is on quality. Let's move on.

Current page: Intel, AMD, And Nvidia: Decode And Encode Support

Prev Page Image Quality: Examined Next Page Transcoding Quality Revisited: CUDA Problems?-

spoiled1 Tom,Reply

You have been around for over a decade, and you still haven't figured out the basics of web interfaces.

When I want to open an image in a new tab using Ctrl+Click, that's what I want to do, I do not want to move away from my current page.

Please fix your links.

Thanks -

spammit omgf, ^^^this^^^.Reply

I signed up just to agree with this. I've been reading this site for over 5 years and I have hoped and hoped that this site would change to accommodate the user, but, clearly, that's not going to happen. Not to mention all the spelling and grammar mistakes in the recent year. (Don't know about this article, didn't read it all).

I didn't even finish reading the article and looking at the comparisons because of the problem sploiled1 mentioned. I don't want to click on a single image 4 times to see it fullsize, and I certainly don't want to do it 4 times (mind you, you'd have to open the article 4 separate times) in order to compare the images side by side (alt-tab, etc).

Just abysmal. -

cpy THW have worst image presentation ever, you can't even load multiple images so you can compare them in different tabs, could you do direct links to images instead of this bad design?Reply -

ProDigit10 I would say not long from here we'll see encoders doing video parallel encoding by loading pieces between keyframes. keyframes are tiny jpegs inserted in a movie preferably when a scenery change happens that is greater than what a motion codec would be able to morph the existing screen into.Reply

The data between keyframes can easily be encoded in a parallel pipeline or thread of a cpu or gpu.

Even on mobile platforms integrated graphics have more than 4 shader units, so I suspect even on mobile graphics cards you could run as much as 8 or more threads on encoding (depending on the gpu, between 400 and 800 Mhz), that would be equal to encoding a single thread video at the speed of a cpu encoding with speed of 1,6-6,4GHz, not to mention the laptop or mobile device still has at least one extra thread on the CPU to run the program, and operating system, as well as arrange the threads and be responsible for the reading and writing of data, while the other thread(s) of a CPU could help out the gpu in encoding video.

The only issue here would be B-frames, but for fast encoding video you could give up 5-15MB video on a 700MB file due to no B-frame support, if it could save you time by processing threads in parallel. -

intelx first thanks for the article i been looking for this, but your gallery really sucks, i mean it takes me good 5 mins just to get 3 pics next to each other to compare , the gallery should be updated to something else for fast viewing.Reply -

_Pez_ Ups ! for tom's hardware's web page :P, Fix your links. :) !. And I agree with them; spoiled1 and spammit.Reply -

AppleBlowsDonkeyBalls I agree. Tom's needs to figure out how to properly make images accessible to the readers.Reply -

kikireeki spoiled1Tom, You have been around for over a decade, and you still haven't figured out the basics of web interfaces.When I want to open an image in a new tab using Ctrl+Click, that's what I want to do, I do not want to move away from my current page.Please fix your links.ThanksReply

and to make things even worse, the new page will show you the picture with the same thumbnail size and you have to click on it again to see the full image size, brilliant! -

acku Apologies to all. There are things I can control in the presentation of an article and things that I cannot, but everyone here has given fair criticism. I agree that right click and opening to a new window is an important feature for articles on image quality. I'll make sure Chris continues to push the subject with the right people.Reply

Web dev is a separate department, so we have no ability to influence the speed at which a feature is implemented. In the meantime, I've uploaded all the pictures to ZumoDrive. It's packed as a single download. http://www.zumodrive.com/share/anjfN2YwMW

Remember to view pictures in the native resolution to avoid scalers.

Cheers

Andrew Ku

TomsHardware.com -

Reynod An excellent read though Andrew.Reply

Please give us an update in a few months to see if there has been any noticeable improvements ... keep your base files for reference.

I would imagine Quicksynch is now a major plus for those interested in rendering ... and AMD and NVidia have some work to do.

I appreciate the time and effort you put into the research and the depth of the article.

Thanks,

:)