Intel Xeon 5600-Series: Can Your PC Use 24 Processors?

The professional space is peppered with products derived from the desktop. Today we're looking at Intel's Xeon X5680 CPUs, which look a lot like Core i7-980X, only they're optimized for dual-socket platforms. We're also introducing new Adobe CS5 tests.

Introducing Intel's Xeon X5680

Back in 2005, Intel changed the trajectory of desktop computing by introducing its first dual-core Pentium processors. Having realized that it was fighting an uphill battle to try pushing frequencies beyond 10 GHz, the company shifted strategies and put parallelism in it crosshairs.

The thing was that servers and workstations were already employing multi-socket configurations to get work done faster. At the time, Irwindale-based Xeons were getting their behinds handed to them by AMD’s Opteron. Although these dropped into dual-processor boards, they were still single-core chips, aided slightly by the same Hyper-Threading technology we know today.

So, while the adoption of threaded software has seemed slow on the desktop (we enjoy cursing apps like iTunes and WinZip, still stuck in the single-threaded dark ages), business-class workstation machines have enjoyed more elegant utilization of multi-core CPUs for a long, long time. As we debate about the value of a six-core CPU versus quad-core models in a gaming box, the workstation guys are trying to get as much horsepower as possible.

Just imagine the cost savings of going from a single-core, dual-socket system to a dual-core, single-socket box. Or how about the performance gain shifting from a single-core, dual-socket platform to a dual-core, dual-socket configuration? That’s two times the processing resources in the same class of hardware. Buying motherboards and CPUs only gets more expensive as you start looking at four- and eight-way boxes.

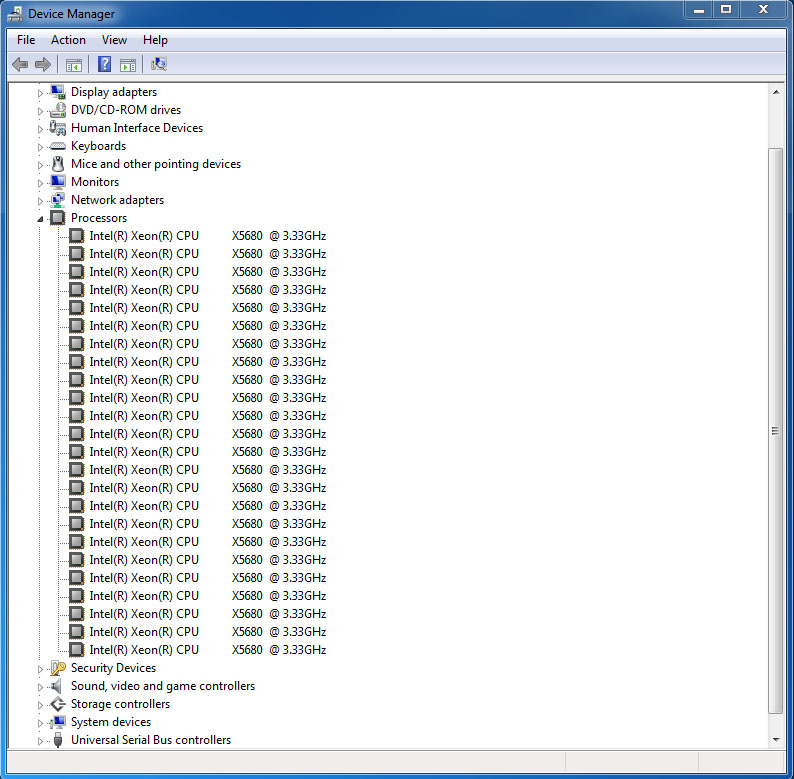

And to think, today we have six-core Hyper-Threaded chips making 12 logical processors available to operating systems like Windows 7—all from a single socket.

Intel’s Return To Competition

As the hardware gets more powerful, software adapts to take advantage, necessitating even more capable hardware. Gotta love the viscous circle, right?

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Last year, Intel launched its Xeon 5500-series CPUs for dual-socket servers and workstations. Then-vice-president Pat Gelsinger characterized the introduction as the most important in more than a decade. And while I’m not one to parrot marketing messages, this one was absolutely true for the company.

The architectural advantage AMD carved out for itself using HyperTransport was especially pronounced in multi-socket machines, while Intel relied on shared front side bus bandwidth for processor communication. With the Xeon 5500-series, Intel addressed its weaknesses through the QuickPath Interconnect, adding Hyper-Threading and Turbo Boost to further improve performance in parallelized and single-threaded applications alike.

Of course, the wheels of progress continue to spin. This year’s shift to 32 nm manufacturing gave Intel the opportunity to add complexity to its SMB-oriented processor lineup without altering its thermal properties. Enter the Xeon 5600 family, sporting up to six physical cores and 12 MB of shared L3 cache per processor—all within the same 130 W envelope established by the Xeon 5500-series.

Take note: you aren’t going to see any AMD CPUs in this piece. When we approached the company early on about participating in a workstation-based comparison to the latest Xeon CPUs, the company conceded that it really isn’t a player in the workstation market right now. Part of being competitive there means pairing competent processors with at least somewhat-modern core logic. And while Intel’s Xeon 5500- and 5600-series chips have the 5520 and 5500 chipset to lean on, AMD’s options for workstation-class chipsets are a little sparser. The company does have its SR56x0 lineup and SP5100 south bridge (and Tyan even sells dual-socket motherboards based on that platform). For one reason or another, though, we didn’t get much interest from AMD. It’s a shame, too. Back when the Athlon 64 launched, its exclusive 64-bit architecture was considered a big win for the digital audio workstation folks.

At any rate, we have plenty of hardware to compare here, including a pair of Xeon 5600s, two Xeon 5500s, and a Core i7-980X that’ll demonstrate where and when a second processor will actually buy extra performance in a workstation-oriented load.

Current page: Introducing Intel's Xeon X5680

Next Page Meet The Xeon 5600 Family-

enzo matrix one-shotOr 24 Logical CPUs, not really Processors.Misleading title. I was excited because I assumed intel had finally come out with 12-core server CPUs.Reply -

Tamz_msc I was expecting an even better performance from these CPUs.The performance is still limited by the software you use.Reply -

shin0bi272 Enzo MatrixMisleading title. I was excited because I assumed intel had finally come out with 12-core server CPUs.they could have gone 4x 6 core cpus without HT too.Reply -

cangelini Enzo MatrixMisleading title. I was excited because I assumed intel had finally come out with 12-core server CPUs.Reply

The Xeon 5600-series tops out with 6 cores and 12 threads, yielding 24 logical processors between two sockets. =) -

wh3resmycar ReplySo many cpu's in task manager...do all but 1 go unused running a single threaded app? shame intel had to go this route with more cores instead of making single core with hyper-threading work faster. you should really only need 2 logical cpu's and hyper threading accomplishes it with 1.

i have a feeling you dont understand what the word "workstation" means. -

Hyper threading was kind of cool back in the P4 days, but now I don't see the point. Virtually nothing that >people actually use< has any benefit to see from it.. It just makes for cool screenshots imo..Reply

I guess what this review says is that, if you want performance for stuff you do at home you should pretty much just get a Nehalem i7 6c with some fast ram. The xeons seems to be behind on everything multimedia, much as expected. -

Otus cangeliniThe Xeon 5600-series tops out with 6 cores and 12 threads, yielding 24 logical processors between two sockets. =)You should have written "logical processors" or "logical cores" and no one would have argued.Reply

mheagerNot true. Hyper threading makes it so if one app gets stuck in an endless loop it doesn't suck up all the cpu and freeze the computer.The OS can do that even on a single core with no HT. Not to mention the case with many physical cores which non-HT CPUs have nowadays. -

kokin mheagerNot true. Hyper threading makes it so if one app gets stuck in an endless loop it doesn't suck up all the cpu and freeze the computer.But why should it get stuck in an endless loop with all that computing power?Reply