Goodbye, Windows 10 — how a decade of 'progress' eroded users' command over their own machines

What should an operating system be: a tool, or a service?

Today, on October 14th, 2025, Microsoft is ending mainstream support for Windows 10, the operating system that ten years ago was famously billed as "the last version of Windows." For many, the announcement doesn't feel like progress. It feels like an eviction.

Over the last several months, users have been scrambling to prepare for life after Windows 10. Microsoft offers a stopgap in the form of Extended Security Updates (ESU) — a one-year lifeline that costs either a $30 one-time fee or, tellingly, a Microsoft Account and OneDrive signup. (Users in the EEA just have to sign in with an MS account.) Others have moved to Linux, Mac, or other alternatives. Still, some have chosen a quieter resistance: staying on Windows 10 without updates, reasoning that it will work for at least a few more years before unpatched exploits make that too risky.

What unites all three groups is fatigue. After a decade of "as-a-service" computing, Windows users are tired of fighting the operating system that is supposed to work for them, not the other way around.

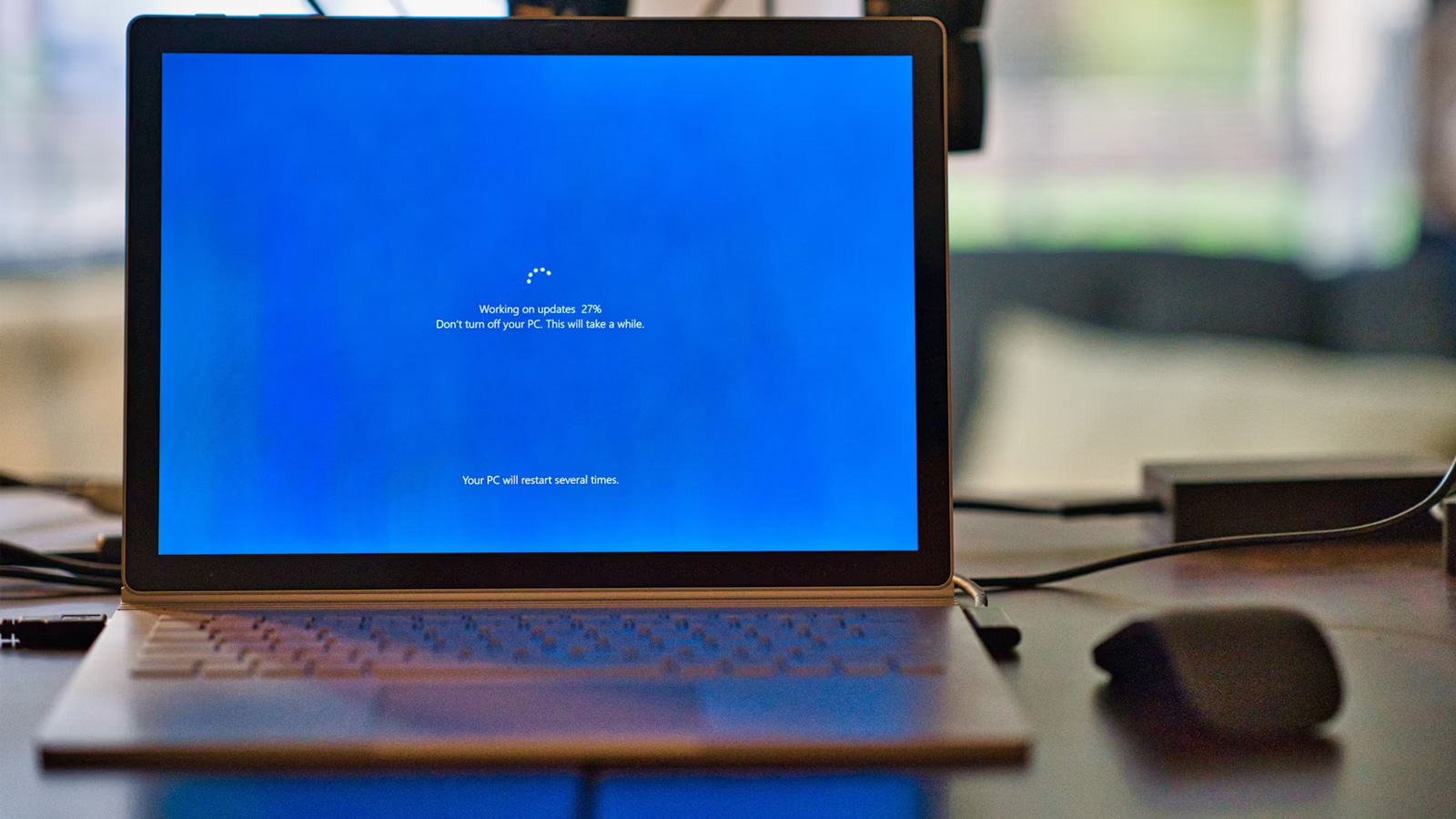

When Windows 10 launched in 2015, Microsoft sold it as the end of version churn. Updates would be continual, seamless, and free, marking the beginning of Windows as a "living platform." In practice, that meant Windows 10 became the prototype for an entirely new relationship between user and machine: one mediated by Microsoft's servers. Telemetry was always on, and updates were always coming. Cortana listened whether you wanted her to or not, and everything you typed in your Start search got sent to Redmond.

Still, for all its faults, Windows 10 found its footing. It booted fast, ran more-or-less reliably, and crucially, it allowed people to ignore the majority of its "cloud integration" if they chose. The operating system still mostly felt like a tool, not a portal. Then came Windows 11, and the line between tool and service finally collapsed.

Users' frustration with Windows 11 isn't born of Luddism, miserliness, or nostalgia. It's that the "new" operating system — "new" as it has actually been out for four years already — represents the culmination of a long cultural drift inside Microsoft that treats the computer less as personal property and more as a rented interface to corporate infrastructure. Microsoft has largely ignored negative feedback since its release, and the frustrations have mounted high.

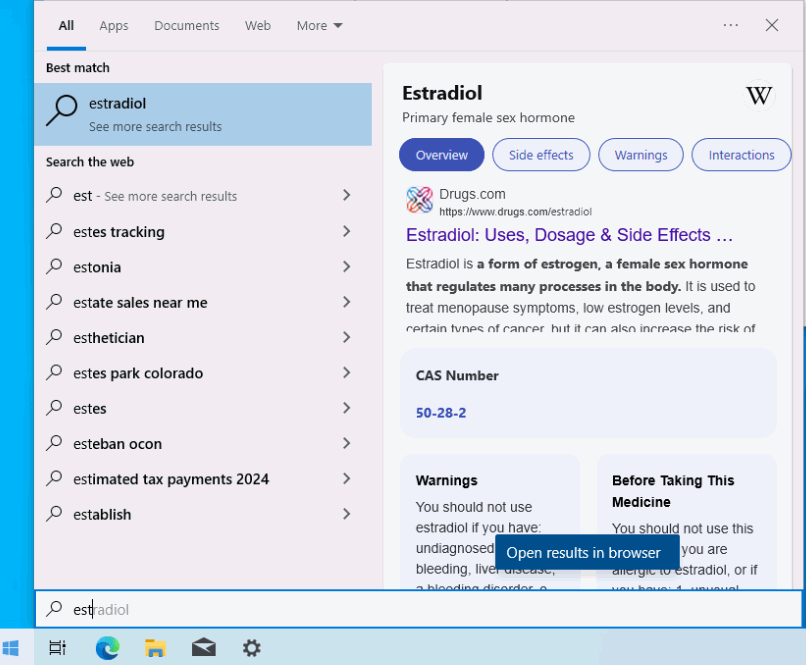

Users' complaints are everywhere: a taskbar that can't be repositioned, a Start menu that favors web results over local ones, nagging users to use Edge, first-party bloatware that reinstalls itself after every update, third-party bloatware that siphons your data, telemetry that cannot be fully disabled unless you're running an Enterprise edition, and even Office defaulting to OneDrive for every saved file. Windows 11's most basic interface, the Start Menu, has been gloriously redesigned in React Native to be slower and heavier than ever before. Every single part of the operating system feels like a triumph of form over function.

There's also the elaborate security theater based on threat models designed for corporate IT departments and then inflicted upon individuals: features like Windows Defender that can't truly be disabled, prompts about Windows Firewall if you turn it off, cumulative updates that cannot be declined in part or in whole, and background services that refuse to stay dead.

This paternalism didn't start yesterday, or even with Windows 10; Microsoft's confidence in its own correctness has been part of the company's DNA for at least thirty years. Windows 95 marked the first real step toward locking users out of their own machines. Windows 95 decided it knew better, that managing the OS internals was too dangerous for mortals, and hid them away behind layers of menus and wizards. Later came the forced integration of Internet Explorer, which was so audaciously anti-choice that the U.S. Department of Justice eventually had to intervene.

In 2001, Windows XP brought product activation — a radical concept considered draconian at the time — and a dumbed-down user interface. Vista followed, over-engineered for a hardware future that hadn't arrived yet and throttled by intrusive User Account Control prompts. Users rebelled by staying on XP for nearly a decade until Windows 7 arrived, not that it was actually materially different from Windows Vista on the most contentious points.

The release of Windows 8 in late 2012 was arguably the purest expression of Microsoft's "father knows best" attitude. It replaced the familiar desktop with a tablet-centric Start Screen, insisting that everyone wanted the same full-screen "Metro" experience, whether they had a touchscreen or not. Businesses and power users revolted, and Microsoft hastily backtracked with 8.1 — arguably the last major release to increase user agency, instead of eroding it.

By the time Windows 10 arrived in 2016, the company had fully embraced Silicon Valley's new favorite paradigm: "software as a service." The operating system became a recurring relationship, not a product you owned; updates and telemetry were no longer optional, tedious security features came pre-installed and locked in place, and the line between local computing and the cloud began to blur (or at least, that was Microsoft's intention).

Many of these changes do stem from legitimate concerns. The modern internet is hostile, and unsecured machines can become easy botnet fodder. The average user doesn't want to manage updates or antivirus software. Microsoft's paternalism is in part a by-product of trying to protect people from their own neglect.

The problem is that every single one of these changes makes assumptions about what the user wants or needs, and in many cases, there's no route back from Microsoft's opinionated defaults. It's true that backups are good and that most people are negligent about doing them. That doesn't mean the OS should throw up "security warnings" because you didn't sign up for OneDrive. It's also true that some people enjoy AI assistants. However, deeply integrating it into every aspect of a PC without the user's consideration is frustrating to witness.

A clear line can be drawn at how the company's solutions serve its own business interests first and foremost. Each layer of automation, every bit of forced integration — OneDrive, Edge, Bing, Copilot, Recall — makes Windows more dependent on Microsoft's ecosystem. You can almost hear the villainous declaration from on high in the corporate boardrooms: "If giving users control makes things messy, then simply remove their control!"

That logic might make sense for casual consumers, but it alienates the enthusiasts and professionals who still define the Windows experience. Casual users have largely moved on to smartphones, tablets, and Chromebooks; Windows 11 is increasingly seen as an unwieldy relic for nerds. For power users, Windows 11 isn't just inconvenient; it's insulting. The OS has become deeply opinionated software aimed at a hypothetical user who is happily served by their smartphone or tablet.

As Windows 10 fades into obsolescence, the argument it leaves behind is more philosophical than technical. What should an operating system be: a tool, or a service? A tool is something you wield, something you control. A service is something you accept, that you acquiesce to. When an update resets your settings, when telemetry can't be disabled, and when your desktop becomes a marketing vector for cloud subscriptions, none of that is a neutral design choice — it's a tacit declaration about who's really in charge.

Indeed, Windows 11 makes it crystal clear: the computer exists to serve Microsoft's vision, not yours. That, more than any missing feature or bloated process, is why users cling to Windows 10 even as support ends. They're not merely resisting change; they're defending a shrinking space of autonomy in a world where every machine wants to manage them, instead of the other way around.

Just as Microsoft said, Windows 10 truly was the last version of Windows — in spirit, at least — because it was the last one that pretended to belong to the user. Today's end-of-support deadline isn't just a technical milestone; it's a symbolic one. A decade after promising to end the version treadmill, Microsoft has built a new kind of treadmill altogether: one that moves beneath you whether you like it or not. What comes next looks less like an operating system and more like a subscription shell; a managed habitat where every click, every login, and every saved document routes through Microsoft's cloud.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our latest news, analysis, & reviews in your feeds.

Zak is a freelance contributor to Tom's Hardware with decades of PC benchmarking experience who has also written for HotHardware and The Tech Report. A modern-day Renaissance man, he may not be an expert on anything, but he knows just a little about nearly everything.