Nvidia is turning GPUs into capital, but questions exist around sustainability — AI companies are financing hardware like debt, as bank warns of 'sharp market correction'

From xAI’s $20 billion debt package to OpenAI’s prepaid clusters, the GPU shortage has created a new kind of financial asset.

Compute used to be something you rented. You spun up a few cloud instances and paid your AWS bill. If you needed more, you just scaled up your usage. That model still exists, but with the generative AI boom, it’s breaking down.

Supply shortages and hardware hoarding, alongside capital excess, have given rise to a strange model where AI companies are financing GPUs in the same way airlines finance planes — via multi-billion dollar debt, leaseback schemes, and vendor equity.

The latest in a growing list of examples is xAI, Elon Musk’s not-so-quiet rival to OpenAI, which is reportedly raising $20 billion to fund GPU purchases. According to reporting by Bloomberg, citing unnamed insiders, around $12 billion of that will be debt routed through a special-purpose vehicle, which buys chips from Nvidia and leases them back to xAI. Nvidia itself is fronting $2 billion in equity, a sign that Nvidia believes that xAI’s scale will pay off. The chips are destined for the Colossus 2 buildout, xAI’s South Memphis megasite, which Musk wants to expand to 200,000 GPUs.

This isn’t a one-off for Nvidia. The company also struck a much larger deal with OpenAI last month, investing as much as $100 billion across multiple years in a structure that effectively pre-funds a 10 GW GPU roadmap. That deal isn’t based on debt or cloud credit, though; it’s prepaid infrastructure in exchange for non-voting equity, tied to future product delivery. That money flows from Nvidia to OpenAI, then back to Nvidia through hardware purchases.

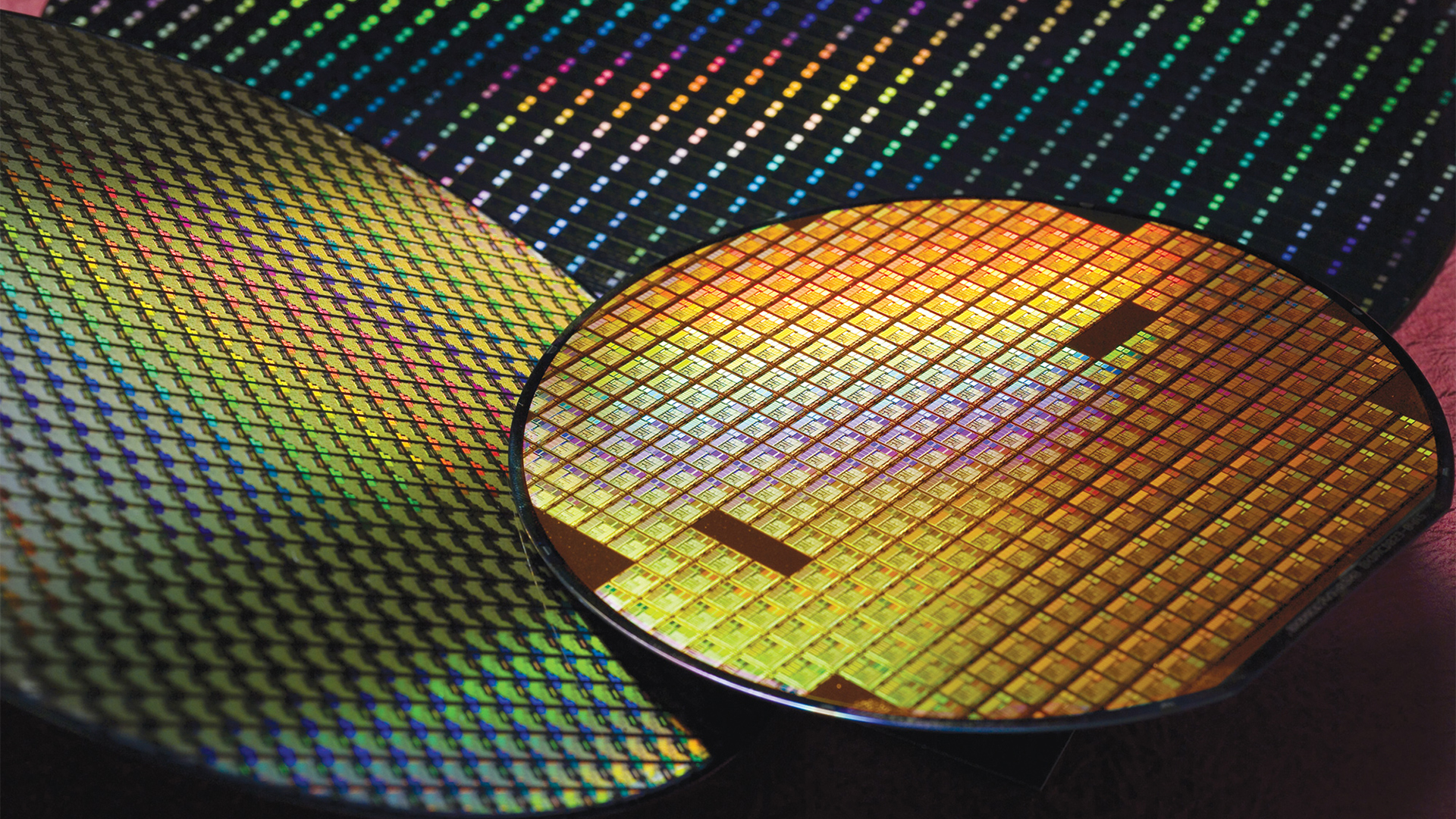

Silicon-backed debt

CoreWeave raised $2.3 billion in debt last year, backed by Nvidia H100s, treating its inventory like collateral. Lambda followed with a $1.5 billion leaseback deal, renting its own servers to Nvidia, which became its largest customer. These are early examples of what’s becoming a new norm of start-ups financing GPUs first and building business models second. After all, you don’t have to prove revenue when your assets appreciate with every generation.

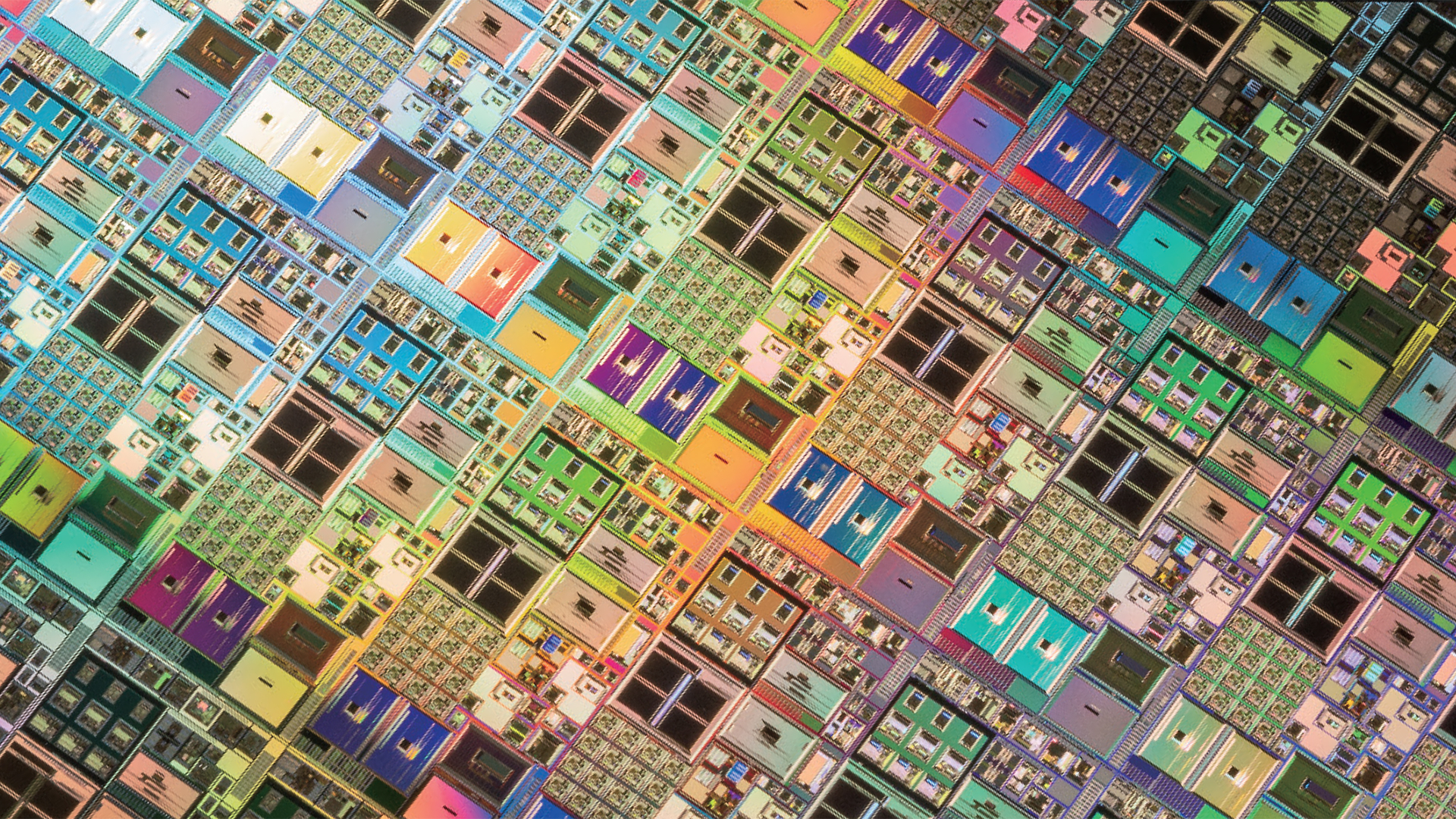

This all points to the changing role of the GPU itself as a balance-sheet asset that’s tradable, leasable, and sometimes, more valuable than the company holding it. That transformation is driven in part by persistent shortages. With Nvidia’s chips in limited supply and overwhelming demand from every corner of the AI market, simply having physical access to GPUs creates a whole lot of leverage. But, arguably, the more influential factor is Nvidia’s lock on the AI training market. When demand exceeds supply, ownership becomes leverage, and Nvidia is structuring deals to keep it that way.

AMD’s OpenAI deal looks cautious by comparison

AMD recently announced its own blockbuster deal with OpenAI, comprising six gigawatts of Instinct MI450 capacity, tied to performance milestones and a public stock price target. It’s structured as a warrant: If OpenAI buys the full amount and AMD’s stock hits $600, it can acquire up to 160 million shares at one cent each — almost 10% of the company.

Unlike Nvidia’s cash-for-hardware deals, AMD’s doesn’t fund GPU purchases but rather, rewards them. There’s no equity transfer until the first gigawatt is deployed, and the full stake only vests if OpenAI executes at scale. That makes it more of a performance incentive than a financing mechanism whereby OpenAI gets upside while AMD gets validation. But the chips still need to be built and delivered.

That alone makes the deal more conservative in comparison to those made by Nvidia, and potentially more sustainable. Nvidia’s arrangements offer immediate compute but raise questions about circular financing: Are customers buying chips because they need them, or because the vendor is helping them foot the bill? AMD doesn’t have that luxury and has to sell on merit alone.

A circular capital bubble?

Regardless, OpenAI’s deal shouldn’t be dismissed as a hedge against Nvidia. Sources familiar with the company’s roadmap say AMD’s current-gen MI300X has already been qualified for inference workloads. It has a bigger memory pool than the H100 and performs well under LLM loads. The MI450 series, expected next year, will ramp alongside Nvidia’s Blackwell-based GB200 systems. But while Nvidia remains allocation-bound, AMD has capacity.

It’s also the first time that OpenAI has made a long-term commitment to non-Nvidia silicon (aside from rumors about it building its own chips with Broadcom), giving AMD a major foothold that comes with a chance to scale software and win mindshare in an ecosystem still dominated by CUDA. It also provides OpenAI with compute flexibility; if the market tightens further, having two suppliers could mean everything. But AMD is still playing catch-up because it doesn’t have the volume, customer base, or vendor leverage that Nvidia enjoys. Its ROCm software stack might be improving, but CUDA is well ahead, and the financing gap — who pays upfront, who delivers when — still favors Nvidia.

Ultimately, there’s a growing sense that the AI hardware market and, indeed, the AI space in general, is running hot. Enthusiasts, analysts, and regulators alike are all asking whether demand is real or, rather, reflective of a feedback loop where GPU orders inflate valuations, which fund more orders, which inflate valuations again. The Bank of England has warned of a dot-com-era risk of a “sharp market correction” in AI-linked equities, reports Financial Times.

OpenAI’s recent valuation puts it near $500 billion, most of which is based on theoretical and future compute. It’s wrong to say that all this is Nvidia’s doing, but the company is undoubtedly at the center of it. When the supplier becomes the investor, the lender, and the customer, the boundaries between growth and leverage begin to break. Right now, everyone’s a winner, but if AI workloads don’t scale fast enough to absorb all that compute, the consequences could be dire.

AMD’s slower, more disciplined approach might pale in comparison to what Nvidia is doing, but it also carries fewer risks. Its OpenAI deal doesn’t put equity on the table until performance is proven. And if demand cools or customers retrench, AMD won’t be left holding the bag. Nvidia’s strategy might have made it the most valuable chipmaker in history, but it’s also made it a quasi-financial institution, allocating capital as much as silicon. That might work brilliantly right now, but will it continue to work when the bills come due?

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our up-to-date news, analysis, and reviews in your feeds. Make sure to click the Follow button.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.