Update: Nvidia Titan X Pascal 12GB Review

Meet GP102

Editor's Note: We've updated the article to include power, heat, and noise measurements on pages seven and eight, and we've made edits to our conclusion to reflect those measurements (see page 10).

You have a knack for trading the British Pound against the Japanese Yen. You have a killer hot sauce recipe, and it’s in distribution worldwide. You just made partner at your father-in-law’s firm. Whatever the case, you’re in that elite group that doesn’t really worry about money. You have the beach house, the Bentley, and the Bulgari. And now Nvidia has a graphics card for your gaming PC: the Titan X. It’s built on a new GP102 graphics processor featuring 3584 CUDA cores, backed by 12GB of GDDR5X memory on a 384-bit bus, and offered unapologetically at $1200.

Before a single benchmark was ever published, Nvidia received praise for launching a third Pascal-based GPU in as many months and criticism for upping the price of its flagship—an approach that burned Intel when it introduced Core i7-6950X at an unprecedented $1700+. Here’s the thing, though: the folks who buy the best of the best aren’t affected by a creeping luxury tax. And those who actually make money with their PCs merrily pay premiums for hardware able to accelerate their incomes.

All of that makes our time with the Titan X a little less awkward, we think. There’s no morning-after value consideration. You pay 70% more than the cost of a GeForce GTX 1080 for 40% more CUDA cores and a 50% memory bandwidth boost. We knew before even receiving a card that performance wouldn’t scale with cost. Still, we couldn’t wait to run the benchmarks. Does Titan X improve frame rates at 4K enough to satisfy the armchair quarterbacks quick to call 1080 insufficient for max-quality gaming? There’s only one way to find out.

GP102: It’s Like GP104, Except Bigger

With its GeForce GTX 1080, Nvidia introduced us to the GP104 (high-end Pascal) processor. In spirit, that GPU succeeded GM204 (high-end Maxwell), last seen at the heart of GeForce GTX 980. But because the Pascal architecture was timed to coincide with 16nm FinFET manufacturing and faster GDDR5X memory, the resulting GTX 1080 had no trouble putting down 30%+ higher average frame rates than GTX 980 Ti and Titan X, both powered by GM200 (ultra-high-end Maxwell). This made it easy to forget about the next step up, particularly since we knew that the 15.3-billion-transistor GP100 (ultra-high-end Pascal) was compute-oriented and probably not destined for the desktop.

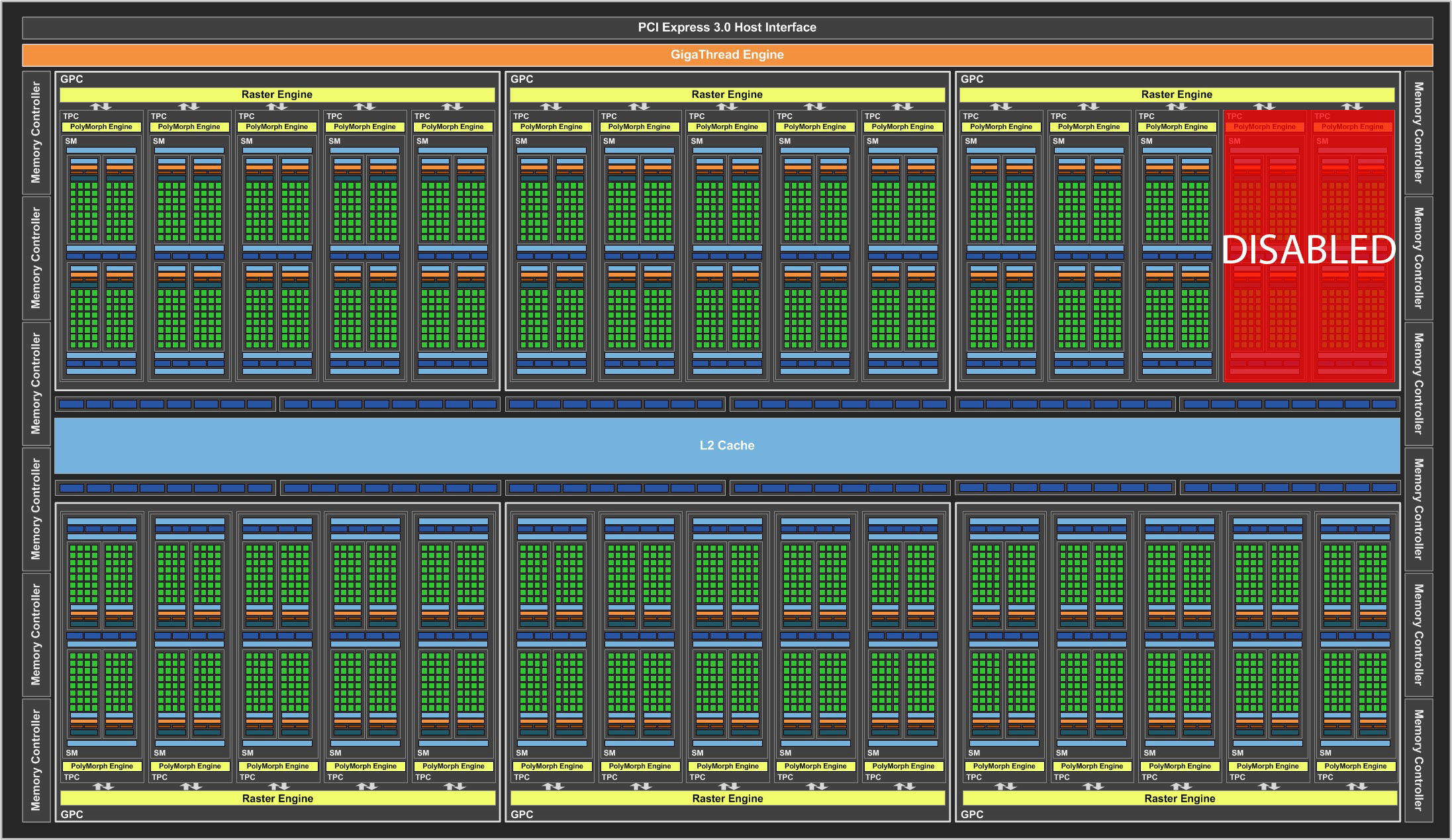

Now, for the first time, we have a ‘tweener GPU of sorts, surrounded by Nvidia’s highest-end processor and GP104. This one is called GP102, and architecturally it’s similar to GP104, only bigger. Four Graphics Processing Clusters become six. In turn, 20 Streaming Multiprocessors become 30. And with 128 FP32 CUDA cores per SM, GP102 wields up to 3840 of the programmable building blocks. GP102 is incredibly complex, though (it’s composed of 12 billion transistors). As a means of improving yields, Nvidia disables two of the processor’s SMs for its Titan X, bringing the board’s CUDA core count down to 3584. And because each SM also hosts eight texture units, turning off two of them leaves 224 texture units enabled.

Titan X’s specification cites a 1417 MHz base clock, with typical GPU Boost frequencies in the 1531 MHz range. That gives the card an FP32 rate of 10.1+ TFLOPS, which is roughly 23% higher than GeForce GTX 1080.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

No doubt, GP104 would have benefited from an even wider memory interface, particularly at 4K. But GP102’s greater shading/texturing potential definitely calls for a rebalancing of sorts. As such, the processor’s back-end grows to include 12 32-bit memory controllers, each bound to eight ROPs and 256KB of L2 (as with GP104), yielding a total of 96 ROPs and 3MB of shared cache. This results in a 384-bit aggregate path, which Nvidia populates with 12GB of the same 10 Gb/s GDDR5X found on GTX 1080.

The card’s theoretical memory bandwidth is 480 GB/s (versus 1080’s 320 GB/s—a 50% increase), though effective throughput should be higher after taking into consideration the Pascal architecture’s delta color compression improvements.

Why the continued use of GDDR5-derived technology when AMD showed us the many benefits of HBM more than a year ago? We can only imagine that during the GP102’s design phase, Nvidia wasn’t sure how the supply of HBM2 would shake out, and played it safe with a GDDR5X-based subsystem instead. GP100 remains the only GPU in its line-up with HBM2.

| GPU | Titan X (GP102) | GeForce GTX 1080 (GP104) | Titan X (GM100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMs | 28 | 20 | 24 |

| CUDA Cores | 3584 | 2560 | 3072 |

| Base Clock | 1417 MHz | 1607 MHz | 1000 MHz |

| GPU Boost Clock | 1531 MHz | 1733 MHz | 1075 MHz |

| GFLOPs (Base Clock) | 10,157 | 8228 | 6144 |

| Texture Units | 224 | 160 | 192 |

| Texel Fill Rate | 342.9 GT/s | 277.3 GT/s | 192 GT/s |

| Memory Data Rate | 10 Gb/s | 10 Gb/s | 7 Gb/s |

| Memory Bandwidth | 480 GB/s | 320 GB/s | 336.5 GB/s |

| ROPs | 96 | 64 | 96 |

| L2 Cache | 3MB | 2MB | 3MB |

| TDP | 250W | 180W | 250W |

| Transistors | 12 billion | 7.2 billion | 8 billion |

| Die Size | 471 mm² | 314 mm² | 601 mm² |

| Process Node | 16nm | 16nm | 28nm |

It’s interesting that Nvidia, apparently at the last minute, chose to distance Titan X from its GeForce family. The Titan X landing page on geforce.com calls this the ultimate graphics card. Not the ultimate gaming graphics card. Rather, “The Ultimate. Period.” Of course, given that we’re dealing with an up-sized GP104, Titan X should be good at gaming.

But the company’s decision to unveil Titan X at a Stanford-hosted AI meet-up goes to show it’s focusing on deep learning this time around. To that end, while FP16 and FP64 rates are dismally slow on GP104 (and by extension, on GP102), both processors support INT8 at 4:1, yielding 40.6 TOPS at Titan X’s base frequency.

MORE: Best Graphics Cards

MORE: Desktop GPU Performance Hierarchy Table

MORE: All Graphics Content

-

adamovera Archived comments are found here: http://www.tomshardware.com/forum/id-3142290/nvidia-titan-pascal-12gb-review.htmlReply -

chuckydb Well, the thermal throttling was to be expected with such a useless cooler, but that should not be an issue. If you are spending this much on a gpu, you should water-cool it!!! Problem solvedReply -

Jeff Fx I might spend $1,200 on a Titan X, because between 4K gaming and VR I'll get a lot of use out of it, but they don't seem to be available at anything close to that price at this time.Reply

Any word when we can get these at $1,200 or less?

I wish I was confident that we'd get good SLI support in VR, so I could just get a pair of 1080s, but I've had so many problems in the past with SLI in 3D, that getting the fastest single-card solution available seems like the best choice to me. -

ingtar33 $1200 for a gpu which temp throttles under load? THG, you guys raked AMD over the coals for this type of nonsense, and that was on a $500 card at the time.Reply -

Sakkura Interesting to see how the Titan X turned into an R9 Nano in your anechoic chamber. :DReply

As for the Titan X, that cooler just isn't good enough. Not sure I agree that memory modules running 90 degrees C is "well below" the manufacturer's limit of 95 degrees C. What if your ambient temperature is 5 or 10 degrees higher? -

hotroderx Basically the cards just one giant cash grab... I am shocked toms isn't denouncing this card! I could just see if Intel rated a CPU at 6ghz for the first 10secs it was running. Then throttled it back to something more manageable! but for those 10 secs you had the worlds fastest retail CPU.Reply -

tamalero Does this means there will be a GP101 with all core enabled later on? as in TI version?Reply -

hannibal TitanX Ti... No, 1080ti is cut down version. Most full ships will go to professinal cards and maybe we will see TitanZ later...Reply

-

blazorthon An extra $200 for a gimped cooler makes for a disappointing addition to the Titan cards.Reply