Five Z97 Express Motherboards, $160 To $220, Reviewed

Intel’s “mainstream” socket continues to spawn enthusiast parts with the company’s fastest-ever gaming-oriented CPU. You’ll probably want a feature-packed motherboard for that, and five companies stepped up to show off the best of the sub-$220 segment.

Results: Overclocking

| BIOS Frequency and Voltage settings (for overclocking) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | ASRock Z97 Extreme6 | Asus Z97-Pro(Wi-Fi ac) | Gigabyte Z97X-UD5H | MSI Z97 MPower | Supermicro C7Z97-OCE |

| Base Clock | 90-300 MHz (0.1 MHz) | 80-300 MHz (0.1 MHz) | 80-333 MHz (0.01 MHz) | 90-300 MHz (0.05 MHz) | 0-655.34 MHz (0.01 MHz) |

| CPU Multiplier | 8x-120x (1x) | 8x-80x (1x) | 8-80x (1x) | 8-80x (1x) | 1-65534x (1x) |

| DRAM Data Rates | 800-4000 (200/266.6 MHz) | 800-3400 (200/266.6 MHz) | 800-2933 (200/266.6 MHz) | 800-3200 (200/266.6 MHz) | 800-4000 (200/266.6 MHz) |

| CPU Vcore | 0.80-2.00V (1 mV) | 0.01-1.92V (1 mV) | 0.50-1.80V (1mV) | 0.80-2.10V (1 mV) | 0-2.00V (1 mV) |

| VCCIN | 1.20-2.30V (10 mV) | 0.80-2.70V (10 mV) | 1.00-2.40V (10 mV) | 1.20-3.04V (1 mV) | 1.85-2.40V (5 mV) |

| PCH Voltage | 0.98-1.32V (5 mV) | 0.70-1.40V (12.5 mV) | 0.65-1.30V (5 mV) | 0.70-2.32V (10 mV) | 0.96-1.36V (5 mV) |

| DRAM Voltage | 1.17-1.80V (5 mV) | 1.20-1.92V (10 mV) | 1.15-2.10V (20 mV) | 0.24-2.77V (10 mV) | 1.35-1.95V (5 mV) |

| CAS Latency | 4-15 Cycles | 1-31Cycles | 5-15 Cycles | 4-15 Cycles | 3-15 Cycles |

| tRCD | 3-20 Cycles | 1-31Cycles | 4-31 Cycles | 4-31 Cycles | 3-15 Cycles |

| tRP | 4-15 Cycles | 1-31Cycles | 4-31 Cycles | 4-31 Cycles | 3-15 Cycles |

| tRAS | 9-63 Cycles | 1-63 Cycles | 5-63 Cycles | 9-63 Cycles | 9-63 Cycles |

Our original Core i7-4770K was nearly perfect; we could push 4.7 GHz at something less than 1.30 V when we topped it with similarly strong cooling. After extensive tests, we eventually settled on 4.6 GHz at 1.25 V with a mid-sized thermal solution.

Intel’s Haswell cores haven’t changed much in spite of the new models, with a purportedly more advanced thermal material between the heat spreader and die serving as the most notable “Devil’s Canyon” advancement. Our new Core i7-4790K gets that improved TIM, but isn't one of the lucky few CPUs able to reach previously-unseen clock rates. Rather, it needs 1.28 V to hit 4.6 GHz. The only improvement, then, is that we don’t need perfect cooling to run at 1.28 volts.

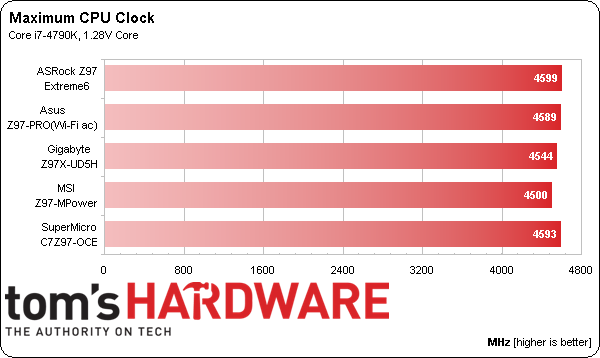

ASRock and Supermicro sent in the highest-overclocking boards this time, with Supermicro achieving the same 46 x 100 MHz setting at noticeably lower temperatures. We’d like to credit its voltage regulator, but haven’t figured out a great way to test that part separately.

Asus didn’t reach 46 x 100 MHz without eventually crashing, but did push 4.59 GHz at 45 x 102 MHz.

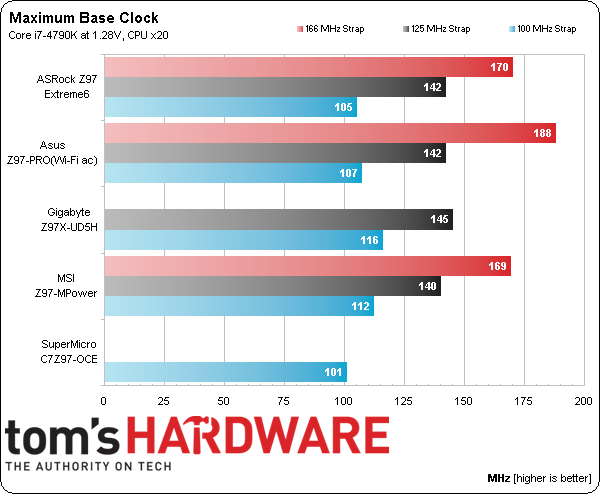

Asus turned in the highest base clock at the top strap setting. Gigabyte’s Z97X-UD5H wouldn’t boot with the 1.66x strap enabled, though a few advanced settings might have helped. Our primary focus on BCLK rests with the 1.00x strap, since that’s where non-K CPUs are stuck, and the Z97S-UD5H leads there, followed by MSI’s second-place Z97 MPower.

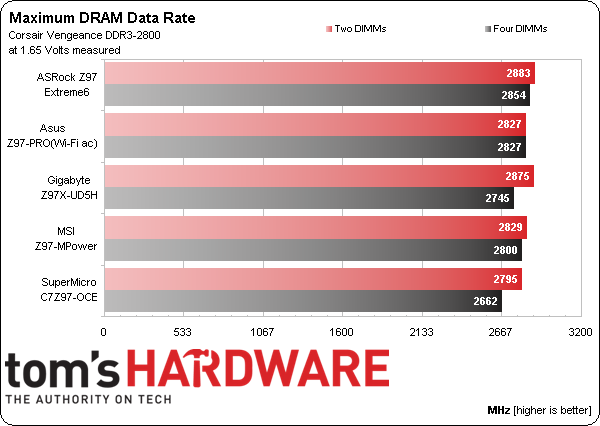

ASRock’s Z97 Extreme6 leads the memory overclocking race, followed by Asus’s Z97-Pro(Wi-Fi ac).

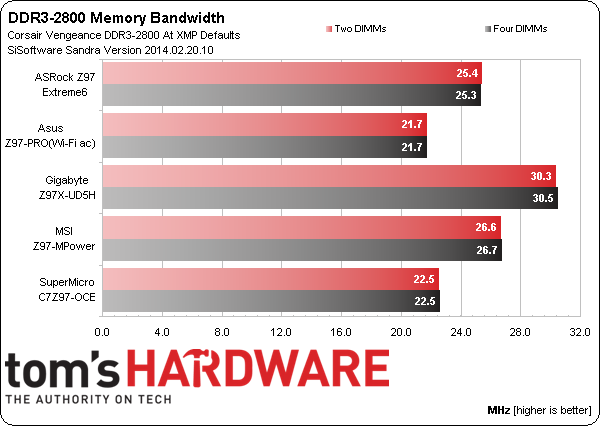

In one of our memory reviews, we noticed that some of Asus’ top-overclocking boards suffer worse memory bandwidth at DDR3-2800 than at DDR3-2400 and decided that a DDR3-2800 memory bandwidth comparison might be a good idea. After all, what good is a top overclock if it ruins your performance?

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Gigabyte has been kicked around in the past for not producing a top memory overclock (and for not having top bandwidth at ordinary data rates). But it would probably be more accurate to say that Asus starts out with optimized settings and applies heavier stability compensation as clocks are increased. Gigabyte’s Z97X-UD5H is the clear leader when DDR3-2800 performance is your priority.

Current page: Results: Overclocking

Prev Page Results: Power, Heat and Efficiency Next Page Which Z97 Motherboard Is Best?-

Memnarchon At this price Asus could send a ROG product (Maximus VII Hero). I wonder why they choose to send the Z97-Pro instead...Reply -

bigshootr8 ReplyAt this price Asus could send a ROG product (Maximus VII Hero). I wonder why they choose to send the Z97-Pro instead...

My thoughts you can find the hero board within that price range quite easy. http://pcpartpicker.com/part/asus-motherboard-maximusviihero -

Drejeck I'd like some ITX Z97 and H97 with M.2 reviewed.Reply

I'm buying the Asus Z97i-plus because it just mount a 2x M.2 2280 and 2260, and all other connectivity goodness, uninterested in overclocking unless the broadwell i5 K consume less than 90W :D -

mapesdhs I recently bought a Z97I-Plus. Being so used to EATX boards as of late, I was a tadReply

stunned at how tiny even the packing box is. :D Just pairing it up with a G3258

initially to see how it behaves. Pondering a GTX 750 Ti, but kinda hoping NVIDIA

will release a newer version in Sept.

Ian.

-

Crashman Reply

They probably wanted to win based on features for the money? We know that the Wi-Fi ac has A $50 WI-FI CONTROLLER, what does the Hero add that's worth $50?13953852 said:At this price Asus could send a ROG product (Maximus VII Hero). I wonder why they choose to send the Z97-Pro instead...

-

lp231 The Asus ROG boards have a red line that lights up showing the audio path through it's build in LEDs, but the mainstream Z97 don't. I had a chance to take a look at one of the Asus Z97 board and took my phone's flash to shine in on it. The color was somewhat yellowish green and it looks really nice.Reply -

g-unit1111 I have a Z97 Extreme 6, it's a very nice board and it's definitely worthy of the approval award.Reply -

TechyInAZ Nice boards!! I love the gigabyte model but I like asus more because yellow heatsinks just don't fit in my opinion.Reply -

Memnarchon Reply

Hello. I think there are more reasons to buy a ROG product, instead of a Wi-Fi controller...13956156 said:

They probably wanted to win based on features for the money? We know that the Wi-Fi ac has A $50 WI-FI CONTROLLER, what does the Hero add that's worth $50?13953852 said:At this price Asus could send a ROG product (Maximus VII Hero). I wonder why they choose to send the Z97-Pro instead...

Better audio quality.

Better MOF-SETs.

Better inductors.

ROG BIOS.

Generally ROG boards have better quality parts.

But in the end we need the reviewers (like you) to review as many products as they can, so we can see the performance difference between them.