How ARM is working its way into PCs and data centers — inside the products and trends behind the hype

Can Arm stick the landing to make good on its lofty goals?

Arm is a company that has existed on the periphery of wholesale dominance for decades. ARM intellectual property has been a part of over 90% of all mobile phones shipped since 2005, currently holding a market share of over 99%, boasting over 250 billion Arm chips shipped since the company's inception. The world’s fastest supercomputer from 2020 to 2022, Fugaku, also ran on ARM CPU cores. The world’s top companies, including Amazon, Google, and Nvidia, have close partnerships with the company and its tech.

And if Arm has anything to say about it, its dominance will only increase over the next decade. The company’s CEO recently claimed that Arm will capture 50% of the Windows PC market by 2029, as well as wishing to penetrate 50% of the data center market by the end of 2025.

The company has made it clear that its scope extends beyond the cellphone, now seeking to become a foundational player in all facets of the computing market. Let’s take a look at the details of this plan, and how Arm is expecting to mount a takeover to surpass Intel, AMD, Nvidia, and the open-standard of RISC-V.

An ARM for Arm — forging an empire without building chips

A crucial note before continuing to write about Arm: Arm is the name of the company and its products, while ARM is the name for its architecture family.

Arm began as Advanced RISC Machines, Ltd., a startup spun off from computer firm Acorn, and funded by Apple. Arm was first known for its invention of the ARM1 Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) and processor, a reduced instruction set computer (RISC) for PCs made in the late 80s. The chip first debuted in the Acorn Archimedes, the first RISC-based PC.

Original developer Sophie Wilson settled on a RISC architecture purely out of budget constraints, with ARM or other RISC ISAs having less power consumption and headroom than ISAs like x86 (the standard for Intel and AMD silicon today). ARM chips were popularized in mobile devices due to their high efficiency and relatively low power draw. The Apple Newton PDA, released in 1993, also ran on an ARM6-based CPU.

Arm’s growth in the market can be attributed to two factors: the highly adaptable nature of the ARM architecture and its unique licensing model. Rather than designing and producing silicon, Arm would license its instruction set and CPU core designs to companies in exchange for an upfront fee and proceeds on eventual silicon sales.

These other companies then receive assistance in turning Arm cores into full CPUs, making Arm a necessary partner with all of its clients. This business model is the same that Arm employs today, allowing it to be the top name in cellphone CPUs without ever producing chips itself.

Arm-designed CPU cores have proliferated widely across the tech landscape. Arm claims it has created the “most pervasive compute footprint in history”, hitting a lifetime 250 billion cores shipped in April of this year.

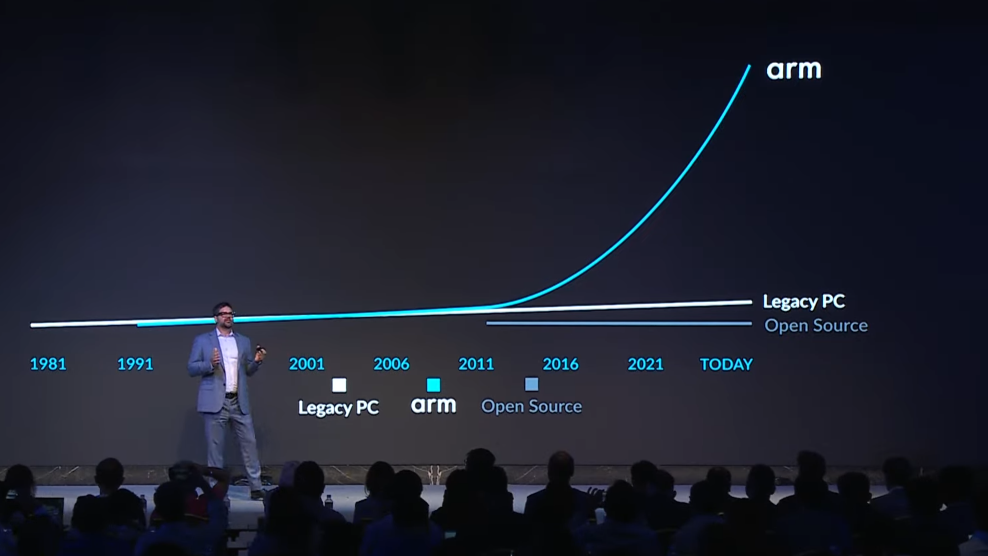

The company could be content with a win in the relatively young ARMv9 architecture, the newest architecture from the company that generates much higher royalties than the previous-gen ARMv8. But a key window into Arm’s mindset as a company comes from this year’s Arm executive summit at Computex, where SVP and GM Chris Bergey highlighted a graph that differentiates Arm from the “legacy PC” world.

Arm’s current goal, is to overthrow the “legacy PC” giants of Intel, Apple, and AMD in the PC and data center space. But, how are its efforts faring so far?

Arm and Windows — an uphill battle

As entrenched as ARM cores are in the mobile world, Windows and macOS are in the PC operating system status quo. Aside from Linux—which, while commonly thought to be a superior OS, is unlikely to reach mainstream appeal anytime soon—all commercially sold PCs are necessarily forced into Windows or Mac for their operating system. ARM-based chips have been part of Apple’s macOS computers in the Apple M-series silicon chips since 2020, but Windows remains a tough nut to crack.

Windows has primarily run on x86-based processors for decades, with x86 being the complex ISA used in Intel and AMD CPUs for just as long. As a result, most of the programs on Windows are programmed to be run on an x86 architecture, and are, in some way, incompatible with ARM-based architecture.

The key to unlocking market penetration among PC users for ARM chips is a bespoke operating system. This effort failed once before with Windows RT, which some may remember as an OS that looked like Windows 8, with a shockingly small selection of compatible programs. Today, Windows on Arm is thankfully a mostly faithful recreation of the x86-based version of Windows 11. This is achieved through extensive emulation, but it still requires ARM-based computers to run it.

Arm’s partnership with Qualcomm birthed the Snapdragon X-series of desktop processors, a wave of ARM-based CPUs in Windows laptops. Launched under the “Copilot+” badge, the laptops were heavily marketed by Microsoft, Arm, and Qualcomm as the future of Windows and of laptops altogether.

The focus on power efficiency with ARM, plus tons of AI-based features and widgets, was touted as the next biggest development in the PC world. CEOs began making absurdly bullish claims, including that Arm would make up 50% of the Windows PC landscape in five years, or that some OEMs expect Snapdragon chips to make up 60% of their sales within three years. In Q3 2024, penetration of the Snapdragon X Elite processors only reached around 0.8% of the market.

However, this hasn’t stopped corporate interests from cherry-picking favorable statistics to maintain hype—Qualcomm recently celebrated the fact that its ARM devices made up 10% of the consumer Windows PC market for devices priced $800 and above.

Part of the reason for disappointing sales may be that ARM’s lead over x86-based chips was not as great as hoped, particularly after Intel and AMD responded with more efficient chips of their own. While our in-house battery tests of Qualcomm's Snapdragon X Elite Copilot+ laptops showed an impressive 15 hours of battery life, the competition from Intel wasn’t far behind at over 13 hours.

This certainly wasn’t the bulletproof efficiency for Snapdragon X that Arm and Qualcomm were hoping for. However, Qualcomm isn't the only company eyeing up ARM CPUs to ship in 2025, as Nvidia has expectations of its own.

Nvidia & Arm: DGX Spark & N1 / N1X chips loom

Nvidia’s DGX Spark and DGX Station AI workstations, originally known as Project Digits, will be powered by the Nvidia Grace CPU, a design based on Arm’s Cortex-X and Cortex-A CPU cores. The AI-focused workstation stirred up an impressive bit of hype on its announcement at CES 2025 and technical showcase at Computex 2025.

In a press Q&A at Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang expressed how useful the DGX Spark might be for developers, who currently rely on the cloud for AI-based computing.

"Every single developer can go out and just get one, and just put it next to their desk. You can develop on here, and you want to now scale it out, or test it out on large data sets, it's just like one pull-down menu, point it at a cloud. Exactly the same thing runs there. And so, this is really an ideal AI developer environment," Huang said.

These systems have the potential to serve AI developers and researchers as systems that can handle larger local AI workloads, thanks to large memory pools. Nvidia has heaps of third parties on board, including Asus, Dell, MSI, and more, to ship the DGX Spark, but the chips have yet to arrive on the market. Additionally, the DGX Station has no solid release date, though targeted for a 2025 release.

Nvidia has high expectations for the DGX systems, especially as the company is enjoying a lofty market cap increase, thanks to its efforts in data center AI. But the DGX systems are not the only chip that Nvidia is looking to ship, with additional ARM-based efforts on the horizon.

Nvidia was expected to be more of a ray of hope for Windows on Arm this year, with one of the most anticipated Computex announcements being the MediaTek/Nvidia collaboration “N1” and "N1X" CPUs. This Windows on Arm CPU was considered a lock for a Computex announcement, but an alleged internal delay to 2026 means that the chips have yet to break cover, at least officially. This delay was reportedly due to efforts to align with Microsoft OS updates, as well as to refining chip-level issues. As of the time of writing, the N1X is alleged to begin mass production in October 2026.

However, the N1X was purportedly spotted in the FurMark benchmark database and scored 4,286 points on the 720p stress test, averaging around 71 FPS. This kind of performance lands the chip at around the same level as an RTX 2060. But this might just be a result of an early engineering sample, for now.

Where are second-gen Snapdragon X products?

So, with Nvidia's consumer efforts sidelined until next year, Qualcomm is currently the only provider of Windows on Arm chips in 2025. But, there have not been any iterative chip releases since last year. Snapdragon X’s second generation was not announced at Computex 2025, meaning the 2nd-gen will likely not launch until 2026 at the soonest.

However, it's expected that the Snapdragon X2 Elite will feature up to 50% more CPU cores when compared to the previous generation, sporting the Oryon V3 CPU architecture. These CPUs are also rumored to be pointing toward the desktop or server market, which stems from Qualcomm testing the SC8480XP chip alongside a 120mm AiO, marking a significant generational change. Qualcomm CEO Cristiano Amon has also teased that the company plans to bring the chips to new form factors.

Snapdragon Summit is set to take place in September, and we may see the next generation of Snapdragon X chips debut there, alongside potential products. But until then, we're still waiting to hear more.

Arm's data center efficiency goals

Arm’s current strongest segment beyond consumer electronics is in the enterprise space. ARM-based chip designs are projected to make up 50% of all compute shipped in 2025 to the top hyperscalers, including Amazon AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, and Alibaba. Each of these firms has its own bespoke ARM-based CPU family, including Amazon’s Graviton, Google’s Axiom, and Alibaba’s Yitian.

Amazon has been a particularly large customer of ARM-based chips for some years now. 50% of AWS’s new CPU stock has been ARM-based Graviton chips since 2021, with more than 90% of the top 1,000 largest AWS EC2 customers currently running Graviton chips. Arm expects its other major clients/partners to follow suit shortly, and for very good reason.

Arm’s Computex 2025 summary claimed that the ARM-powered chips used by the above hyperscalers are up to 40 percent more energy-efficient than other platforms, taking shots at Intel’s Xeon and AMD’s Epyc enterprise lines. The modern data center is a place where energy efficiency is crucial, as power consumption drives skyrocketing operating costs and leads to negative public opinion against AI data centers.

Elon Musk’s Colossus supercomputer, for example, has been accused of illegally polluting the local community with its 30+ portable diesel and methane generators, used to make up the 100+ MW shortfall between what the site needs and what the power grid can give to it.

A 40% increase in energy efficiency, therefore, seems like a critical win for Arm; certainly a more convincing delta than the 11% in power efficiency that Snapdragon X sees over Intel laptops. Arm works with companies to put their names on their bespoke ARM-based chips, resulting in branding wins for hyperscalers and monetary wins for Arm. However, change may be coming on the horizon for Arm that may carry some exceedingly high risk.

In-house chipmaking ambitions

In February, it became widely reported that Arm had seemingly begun recruiting executives and engineers from its licensee customers, looking to build in-house chips. Multiple industry sources allege that Arm recruiters are sending out letters to potential workers, stating Arm’s intent to begin “selling its own silicon, with a focus on driving AI enablement in the data center." Arm had also reportedly already made a deal with Meta to supply the company with its soon-to-come in-house silicon for Meta’s hyperscaling and web hosting endeavor, and a matching deal with TSMC to fabricate the chips.

Arm has so far declined to comment on this claim, which makes a lot of sense. It directly contradicts the testimony of Arm CEO Rene Haas in court against Qualcomm, stating “we don’t build chips” when asked about Arm’s chipmaking ambitions. More than that, it risks alienating Arm from its customers, who would quickly become competitors. Qualcomm and Nvidia both sell ARM-based enterprise CPUs to clients, but if Arm began selling its own silicon, it would suddenly be at odds with its licensees. What’s more, Arm chips would compete against the ARM-based Graviton, Axiom, and Yitian chips licensed by hyperscalers, potentially scaring these clients off of continuing to license from Arm in these custom chips.

Entering the ring as a silicon maker risks losing a large number of top enterprise clients to Intel or AMD, or perhaps even RISC-V. RISC-V is the open-standard counterpart to the privately owned Arm, itself a RISC ISA family that is on the path the becoming mature enough to entertain business from high-end hyperscalers.

RISC-V has emerged as a key part of China’s computing boom, with the Chinese government urging computing companies blacklisted by the U.S. to develop their own chips on the open standard. RISC-V would be attractive as an alternative to ARM-based chips if Arm scares its clients away by turning into a chipmaker.

The risk of Arm losing customers is not as great as it may seem, however. ARM’s key edge over RISC-V is that ARM is not just an architecture; the company also designs CPU cores for license by customers. If a client were to drop Arm, it would then have to design its own CPU cores from the ground up on the RISC-V architecture. This represents a significant R&D cost, as it involves more than just licensing from and collaborating with Arm at a much later stage in development. A company like Amazon, which already uses Graviton CPUs in around 50% of its servers, would not likely start from scratch on RISC-V.

The future of Arm

Arm, like seemingly every other technology company in the modern day, is betting big on AI and its impact on the tech market. Arm GM Chris Bergey described the current iteration of AI as “the single greatest advancement in the history of computing” at Computex this year. With data center expenditures skyrocketing and enterprise hardware quickly progressing, it’s not surprising that a hardware company would make claims like this to sell more products.

Right now, AI is not making a major material difference in the lives of the average adult. As of April 2025, 66% of American adults claim to have never used an LLM chatbot, and of the 33% who have, 61% of them report the experience to have been only somewhat, or not useful. Nevertheless, 83% of businesses claim that AI is a “top priority” for their business plans.

In such a rapidly evolving segment, everyone is looking to make their share of wealth, and Arm is no different. Through data center products, as well as more consumer-facing ones, like Qualcomm's Snapdragon and Nvidia's DGX Spark and DGX Station.

So, we know that Arm is focusing its efforts on shipping AI-ready PCs, whether that be satellite systems for developers or Copilot Plus laptops. With next-generation Snapdragon chips seemingly just around the corner, in addition to another boon from Nvidia's ARM-based CPU efforts, it paints a new picture for the business after a relatively quiet 2025.

If Arm truly wants to be the thing that turns Intel and AMD into “legacy” technology, it needs to stick the landing on its upcoming, theorized big moves into mainstream consumer processors and in-house chipmaking. If it does, Arm could be powering laptops through its Qualcomm and Nvidia collaboration, breaking into the desktop market, and shipping custom chips in the data center.

Should this all come to fruition as the company hopes, it would likely become one of the greatest silicon empires of the modern day.

Sunny Grimm is a contributing writer for Tom's Hardware. He has been building and breaking computers since 2017, serving as the resident youngster at Tom's. From APUs to RGB, Sunny has a handle on all the latest tech news.