Research team shows off potential flash memory successor

San Francisco (CA) - A joint team of scientists from IBM, Macronix, and Qimonda today announced details about a new phase-change memory chip, which they claim marks the next step in finding a successor to the universal flash memory format. The non-volatile memory is estimated to be about 500 times faster than Flash, while using less than one-half the power to write data into a cell.

Phase-change memory offers several advantages over Flash, including the ability to write and read data much more quickly (according to Samsung, about 30 times faster), as well as an infinite lifespan. Current flash memory technologies allow about 100,000 (NOR) and 1 million (NAND) read/write cycles before becoming unreadable, which can cause problems in environments with a huge demand for continuous writing and rewriting, like network or storage systems.

Phase-change random access memory (PRAM) is different than static RAM (SRAM) or dynamic RAM (DRAM), in that the latter formats are volatile, meaning that stored data will be lost when power supply is interrupted. Flash memory is able to maintain stored data even without power supplied to a chip, but in doing so it suffers much slower write/read speeds and continuous degradation of the cells after each read/write cycle.

PRAM, according to the research team, takes the best of both worlds, offering quick data transfer cycles without the volatility of other RAM technologies. Specifically, the research team says that phase-change material can switch more than 500 times faster than flash, while only consuming half the energy. Additionally, phase-change technology will enable chips at a much smaller size than flash memory has been able to. While flash memory chips are expected to become difficult to scale below 32 nm, there's already visibility of 20 nm PRAM chips.

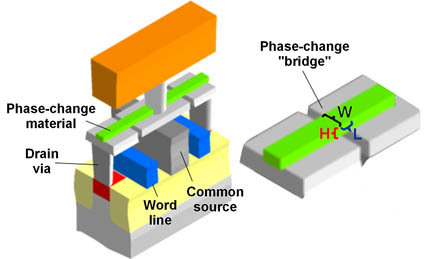

The announced PRAM devices use a new material, which was created at IBM's Almaden Research Center in San Jose. According to a press release, it is a "complex" semiconductor alloy that, say the researchers, can be changed rapidly between an ordered, crystalline phase (which means lower electrical resistance) to a disordered, amorphous phase (with much higher electrical resistance).

Talking about flash successors is hardly a new idea. Two years ago, we took an in-depth look at the formats competing to be the new Flash, and concluded that there was no rush in replacing it. However, earlier this year, another competing memory format, magnetic RAM (MRAM) went into mass production for the first time. MRAM can write data at nearly one million times the rate of Flash, but has yet to reach the storage capacity offered by Flash.

It is unclear whether MRAM will ever be able to scale quickly enough to be have a shot at replacing Flash memory. However, there appers to be no doubt that it may become a match for SRAM in the not too distant future.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Following the MRAM announcement, Samsung stepped up and introduced its plans to replace NOR Flash with PRAM devices, saying it could bring down the size of the structure to just 20 nm, nearly 5000 times thinner than a single strand of hair. According to Samsung, the switchover could happen in less than a decade.

Replacing such a technological institution as Flash is not going to be easy, but with all the money spent on developing new technologies, the companies behind it feel confident about the future of the new technology. Senior VP of Qimonda Wilhelm Beinvogl sums it up by saying, "We have demonstrated the potential of the phase-change memory technology on very small dimensions laying out a scalability path. Thus phase-change memories have the clear potential to play an important role in future memory systems."

Mark Raby is a freelance writer for Tom's Hardware, covering a wide range of topics, from video game reviews to detailed analyses of computer processors.