Second-Generation Ultrabooks: Faster And Cheaper With Ivy Bridge

Ivy Bridge Shows Up At 17 W In Intel's Second-Gen Ultrabook

I don't think there's a doubt in that Apple's MacBook Air set Intel on its tear to help PC manufactures design and build comparably thin, light, and potent notebooks. At least until now, they've seemingly received a lukewarm reception, though, and it's not hard to understand why. The Ultrabooks we've handled haven't really done anything better than Apple's incumbent. And they're still expensive. We all want to get our hands on unobtrusive mobile hardware, but spending a premium for modest performance crammed into a more attractive package is hardly a compelling compromise. We're still waiting for a contender that does everything right.

Thin-and-light notebooks, the precursors to Intel's Ultrabooks, were characterized by 11 to 13" screens, ultra low-voltage processors, and integrated graphics. They made every effort to cut power consumption in the interest of enabling a sexier form factor with good-enough battery life. As a rule, performance took a backseat to simply making thin-and-lights possible.

Apple built its first MacBook Air more than four years ago using a Core 2 Duo processor and, later, add-in graphics from Nvidia. Not surprisingly, then, last year's Sandy Bridge processor architecture made it possible to build similarly ultra-thin machines with notably more performance and improved battery life. What they didn't do, however, was pull down pricing. The first generation of Ultrabooks explicitly called for 17 W Sandy Bridge-based CPUs able to support at least five hours of battery life. And the very cheapest models started around $800.

Intel's Ivy Bridge design is unquestionably more evolutionary than Sandy Bridge if you limit your scope to x86 performance. But the 22 nm manufacturing process it employs helps enable substantially better graphics performance inside of the same 17 W processor ceiling. As a result, the company is convinced that its second-generation Ultrabooks are the ones that'll drive smaller, faster machines into the mainstream space. Already, we've seen Lenovo introduce its IdeaPad U310 based on a Core i3-3217U for $750 after an online coupon.

Mobile Ivy Bridge Today: Dual-Core 35 And 17 W CPUs

Last-gen Sandy Bridge CPUs dipped down into the 17, 25, and 35 W thermal design power range. For a device to be called an Ultrabook, however, it had to employ one of the 17 W Consumer Ultra-Low Voltage (CULV) models. The same holds true for the second-generation Ultrabooks. But because Sandy Bridge was manufactured using 32 nm lithography, while Ivy Bridge is etched at 22 nm, the newer CPUs cram more transistors into the same power budget, mostly dedicated to graphics.

| Mobile Third-Gen Core Family: Dual Core Processors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU SKU | Cores / Threads | Base Freq. | Max. Turbo | L3 Cache | HD Graphics | Graphics Base Freq. | Graphics Max. Freq. | TDP (W) | Price |

| Core i7 | |||||||||

| -3667U | 2/4 | 2.0 GHz | 3.2 GHz | 4 MB | 4000 | 350 MHz | 1.15 GHz | 17 | $346 |

| -3520M | 2/4 | 2.9 GHz | 3.6 GHz | 4 MB | 4000 | 650 MHz | 1.25 GHz | 35 | $346 |

| -3517U | 2/4 | 1.9 GHz | 3.0 GHz | 4 MB | 4000 | 350 MHz | 1.15 GHz | 17 | ? |

| Core i5 | |||||||||

| -3427U | 2/4 | 1.8 GHz | 2.8 GHz | 3 MB | 4000 | 350 MHz | 1.15 GHz | 17 | $225 |

| -3360M | 2/4 | 2.8 GHz | 3.5 GHz | 3 MB | 4000 | 650 MHz | 1.20 GHz | 35 | $266 |

| -3320M | 2/4 | 2.6 GHz | 3.3 GHz | 3 MB | 4000 | 650 MHz | 1.20 GHz | 35 | $225 |

| -3317U | 2/4 | 1.7 GHz | 2.6 GHz | 3 MB | 4000 | 350 MHz | 1.05 GHz | 17 | ? |

| -3210M | 2/4 | 2.5 GHz | 3.1 GHz | 3 MB | 4000 | 650 MHz | 1.10 GHz | 35 | ? |

Consequently Core i5-3667U, -3517U, -3427U, and -3317U are the most interesting to us, since they're the Ivy Bridge-based CPUs aligned with Intel's sub-20 W TDP Ultrabook specification. Compared to the previously-reviewed Core i7-3720QM, which is a better fit in a full-sized notebook, getting getting Ivy Bridge into a 17 W thermal envelope requires halving that larger CPU's number of cores, stripping at least half of its shared L3 cache, dropping clock rates, and cutting into its base graphics frequency.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Fortunately, though, the chip's peak graphics clock rate doesn't change much. While the higher-end 45 W mobile Ivy Bridge processors spin their HD Graphics 4000 engines up to 1.3 GHz, the 17 W parts go as high as 1.15 GHz, matching the potential of a desktop-oriented Core i7-3770K. Further, Hyper-Threading is enabled on these dual-core parts, allowing them to schedule up to four threads at a time.

Mobile Ivy Bridge Nomenclature

Intel attempts to give each character of its model names some sort of meaning. The first digit, in this case a "3," is indicative of the Ivy Bridge architecture, Intel's third-generation Core design. The "M" suffix represents the standard-voltage (35 W) models. Performance-oriented SKUs are flagged by "XM" or "QM" instead, denoting the company's Extreme and quad-core offerings.

Last generation, Sandy Bridge-based models ending with "9" were the low-voltage (LV) parts. Ultra-low-voltage (ULV) chips, the 17 W ones, were identified with a "7." Now, there are no 25 W Ivy Bridge-based CPUs. Rather, there are additional 17 W processors bearing a xxx7U model name. The breakdown is just a little bit simpler.

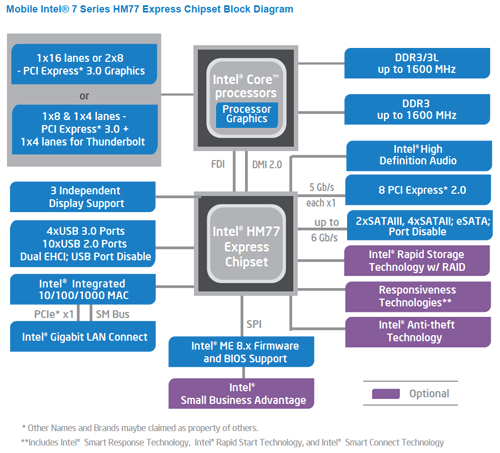

We covered Ivy Bridge as an architecture in Intel Core i7-3770K Review: A Small Step Up For Ivy Bridge, and the details presented there are applicable here as well. However, there is a trio of enhancements that distinguish Intel's 7-series platforms from their predecessors: support for native USB 3.0, provisioning for up to three display outputs, and the option to attach a Thunderbolt controller.

The ability to drive three screens simultaneously is perhaps the most exciting addition, overcoming a limitation of integrated graphics that previously constrained most notebook configurations to one external screen. Ivy Bridge-based CPUs make it possible to use a notebook's panel and up to two attached displays.

Hands-On With Intel's Reference Ivy Bridge-Based Ultrabook

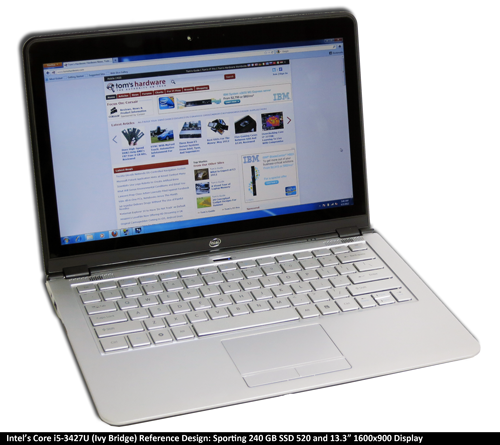

Eager to demonstrate the potential of an Ultrabook in 2012, Intel sent over a reference design, built by its own engineers as a representation of what manufacturers might do with the platform. Although the company was eager to write off any of the system's shortcomings to the fact that it'd never be a retail offering, Intel's concept is thin enough, light enough, and fast enough to be a real, plausible Ultrabook.

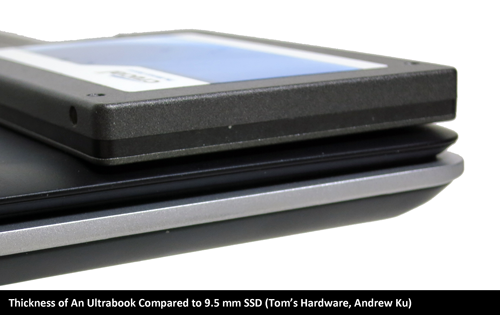

The company armed our little sample with a Core i5-3427U dual-core processor running at 1.6 GHz, 4 GB of memory, and a 240 GB SSD. Its purpose wasn't to expose all of the Ivy Bridge design's features. For example, there is just one HDMI output. But it does also expose two of the chipset's integrated USB 3.0 ports, along with a headphone output and card reader slots. A 1600x900 screen also represents a slight improvement over the 1440x900 display you can currently get in Apple's MacBook Air (though not all Ultrabook vendors will offer that higher resolution).

Putting Intel's Second-Gen Ultrabook To The Test

In an effort to eliminate the variables that can skew our results, we test using an external display rather than our sample's panel. A notebook's LCD can account for more than half of its consumption, and handpicked settings, particularly on a non-retail reference build, throw off power measurements. Driving a separate screen allows us to evaluate the platform's relative power use, allowing us to draw more precise conclusions about the hardware under the hood.

It was no surprise that Intel shipped us its reference second-gen Ultrabook with one of its own SSD 520 drives. However, we chose to standardize on Crucial's 256 GB m4 as the main system drive for our testing, since we had also used it for our higher-end mobile Ivy Bridge coverage and wanted to include those numbers here, too.

Networking benchmarks are run over our Local Area Network to factor out the power differences between wireless solutions.

| Test Hardware: Mobile Systems | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processors | Intel Core i5-2467M (Dual-Core, 1.8 GHz) | Intel Core i5-3427U (Dual-Core, 1.6 GHz) | Intel Core i7-2820QM (Quad-Core, 2.3 GHz) | Intel Core i7-3720QM (Quad-Core, 2.6 GHz) |

| Memory | 4 GB DDR3-1333 | 4 GB DDR3-1600 | 8 GB DDR3-1333 | 8 GB DDR3-1600 |

| Graphics | HD Graphics 3000 | HD Graphics 4000 | HD Graphics 3000 | HD Graphics 4000 GeForce GT 630M |

| Notebook | Acer S3-951-6828 | Intel Reference Design | Unknown Clevo model | Asus N56Vm |

| Hard Drive | Crucial m4 256 GB SATA 6Gb/s | |||

| DirectX | DirectX 11 | |||

| Operating System | Windows 7 Ultimate 64-bit | |||

| Graphics Driver | Intel 8.15.10.2725 | Intel 8.15.10.2725 | Intel 8.15.10.2725 | Intel 8.15.10.2725 Nvidia 301.24 |

Current page: Ivy Bridge Shows Up At 17 W In Intel's Second-Gen Ultrabook

Next Page Benchmark Results: PCMark 7-

sam_fisher It seems that Ivy Bridge's lower TDP and its HD 4000 comes into its own in the notebook/ultrabook market more so than the PC/gaming one.Reply -

sam_fisher crisan_tiberiuthey should use HD 4000 on every intel CPU, i dont get it why they dont ...Reply

The integrated graphics is built into the processor die and the changes between the HD 3000 and 4000 are physical changes, so they can't just change them without changing the whole CPU.

-

mayankleoboy1 crisan_tiberiuthey should use HD 4000 on every intel CPU, i dont get it why they dont ...Reply

Pricing, TDP, segmentation and PROFIT -

crisan_tiberiu sam_fisherThe integrated graphics is built into the processor die and the changes between the HD 3000 and 4000 are physical changes, so they can't just change them without changing the whole CPU. Yes, i know that :)) but when they designed IVY they should have designed every chip with the HD 4000. The HD 4000 is still outperformed by Liano iGPU if you remember...Reply -

tomfreak Cant u put an older/previous generation desktop and benchmark against it? I cant or couldnt get how a fast a 2.0GHz Ivy vs a similar Nehelem Desktop CPU vs desktop core 2 duo CPU. Many of us buy notebook to replace desktop for casual use, we would like to know what it can do vs our old desktop.Reply

Besides get some older AAA games to bench, nobody play BF3 at Ultra books with HD4000. We wanna see what old games we can max out @ full resolution. -

silverblue I think AMD missed a trick with Llano. Instead of throwing four lowly clocked cores at a mobile processor, perhaps two higher clocked cores would've made much more sense. That way, they could possibly sport a higher clock GPU as well within the same TDP.Reply

Trinity's lower powered, higher clocked cores already look to have partly made up for this, but until the 17W variant comes along, there's no real indication of how it'll measure up to IB ULV. However, we do know that AMD pairs the slower GPUs with the slower CPUs and vice versa, so there's little chance of a, say, 2C/2T/1M CPU with the 7660G GPU. -

DjEaZy ... ok... you compare the Llano to Sandy/Ivy bridge in CPU performance, but not in GPU performance? and why not Sandy/Ivy Bridge to Trinity?Reply

... and Adobe Photoshop CS 5? not CS 6?