Researchers create 3D displays that can be seen and felt using optotactile surfaces — millimeter-scale pixels rise into perceptible bumps when struck by brief pulses of projected light

Study demonstrates high-density tactile 3D graphics powered entirely by projected light.

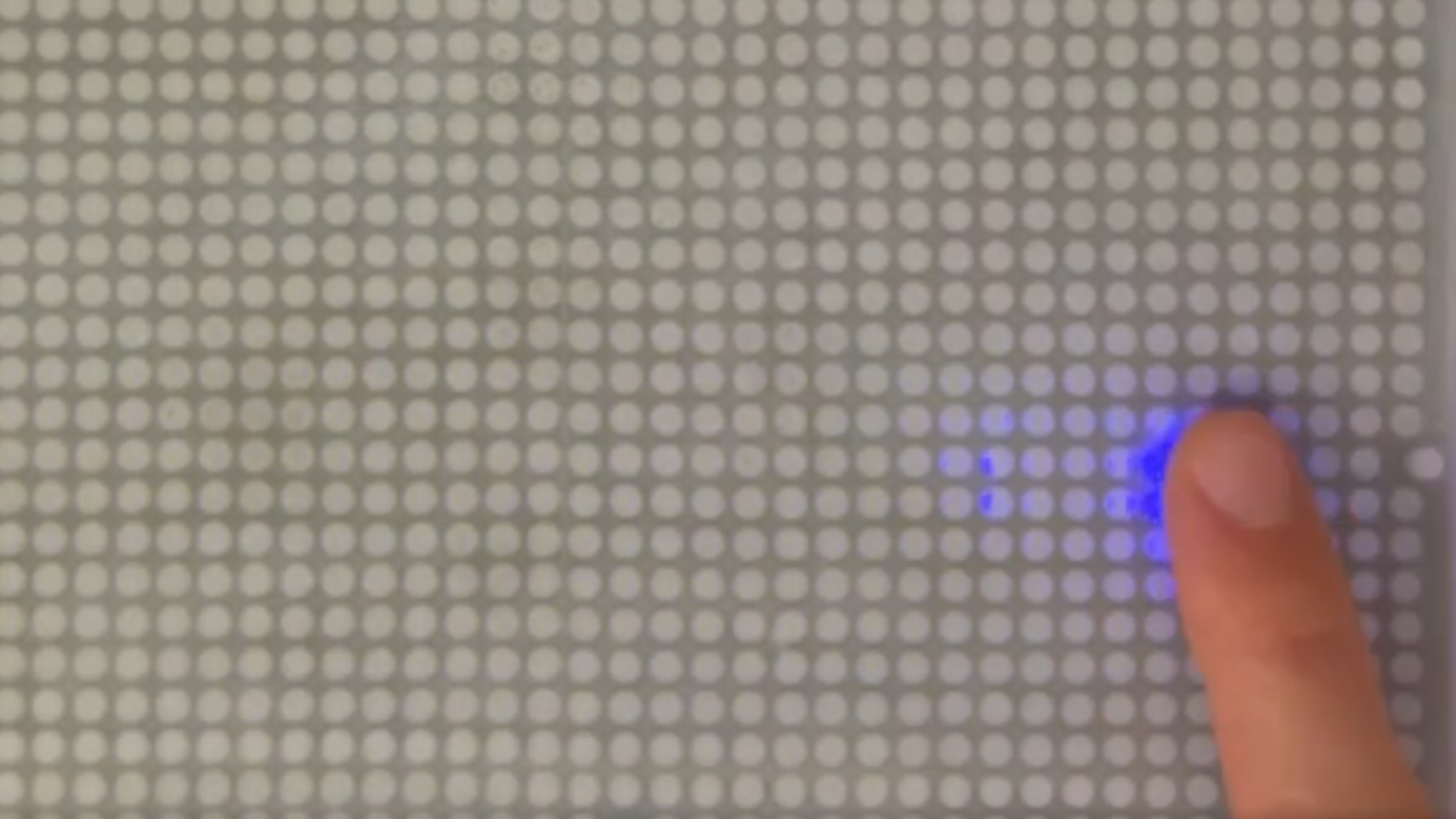

Researchers at UC Santa Barbara have demonstrated a display technology that renders dynamic graphics that can be both seen and physically felt, according to a new study published in Science Robotics. The work introduces thin optotactile surfaces populated with millimeter-scale pixels that rise into perceptible bumps when struck by brief pulses of projected light.

The project began with a simple question UCSB Professor Yon Visell posed in 2021: could the same light that draws an image also generate a mechanical response strong enough to be felt? After a year of modeling and unsuccessful prototypes, UCSB's Max Linnander produced a working proof of concept in late 2022. A single pixel, actuated only by flashes from a small diode laser and containing no embedded electronics, generated a clear tactile pulse when touched.

The full display architecture described in the study was built on that work, with each pixel consisting of a small air cavity beneath a thin surface membrane and a suspended graphite film. When illuminated, the film absorbs and converts light into a rapid temperature rise. The heated air beneath the membrane expands, pushing the surface outward by up to a millimeter.

Fingertip precision

That displacement is large enough for users to locate individual pixels with fingertip precision. Because the same laser beam provides both power and addressing, the panel requires no internal wiring. A scanning system sweeps the beam across the array at high speed, energizing one pixel after another and forming continuous visual and tactile animations.

The team has fabricated arrays with more than 1,500 independently addressable pixels, a significant step up from prior tactile displays that struggled to combine density, speed, and displacement. Response times from two to 100 milliseconds allow the panels to reproduce flowing contours, shapes, and character patterns. In user studies, participants could accurately track moving stimuli, discriminate spatial layouts, and perceive temporal sequences created through sequential pixel activation.

According to the researchers, scalability will follow naturally from the optical addressing scheme. Larger arrays could be driven by the same class of compact scanning lasers used in modern projectors. They also point to potential applications in automotive interfaces that emulate physical controls and electronic texts or diagrams that reshape under a reader’s hand.

Although the work is still a prototype, converting light directly into mechanical deformation at high resolution, the UCSB team has opened a path toward tactile displays that behave much more like visual ones, rendering information as patterns that can be explored by both eye and hand.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our latest news, analysis, & reviews in your feeds.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.