Developer turns floppy disks into secret black-and-white picture canvases — pbm2track "paints" pixel art into the disk's magnetic timing diagram

An intriguing way to repurpose a floppy disk

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The floppy disk might seem next to useless in the modern era of flash memory and solid state drives, but that hasn’t stopped one entrepreneurial hacker from developing a tool that turns the simple floppy into a piece of art. The pbm2track tool takes advantage of a floppy disk’s track timing diagram to “paint” pixel art directly onto the disk itself.

Futuristic as this might sound, it all relies on a slightly more analog approach. Beneath its plastic enclosure, a floppy disk is fundamentally a piece of flexible, circular plastic, coated with a thin layer of magnetic material. Data is stored as microscopic magnetic reversals, or flux transitions, and as the disk is read, the drive’s head detects these reversals as electrical pulses, using the precise timing between them to reconstruct the original bits of data.

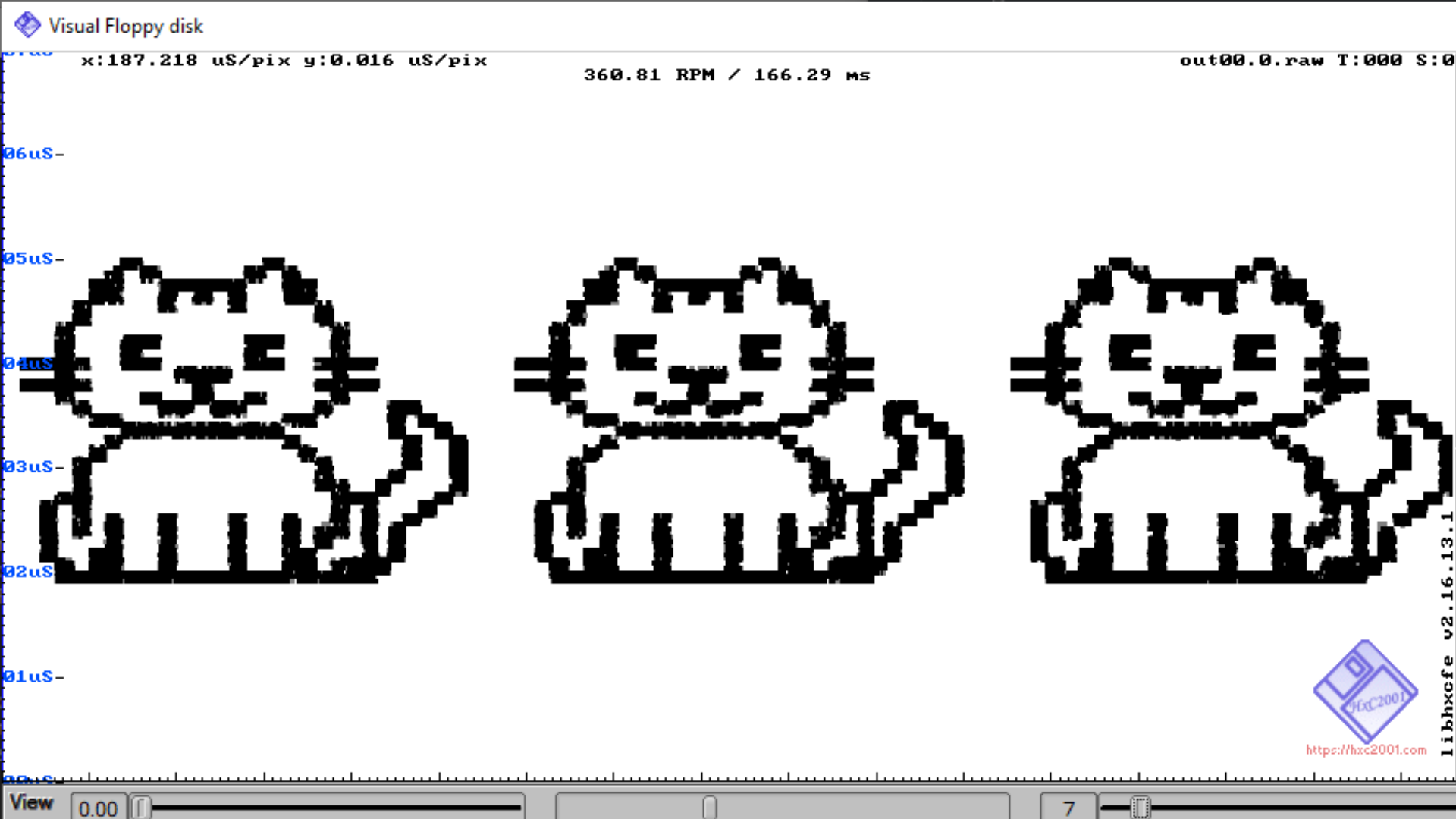

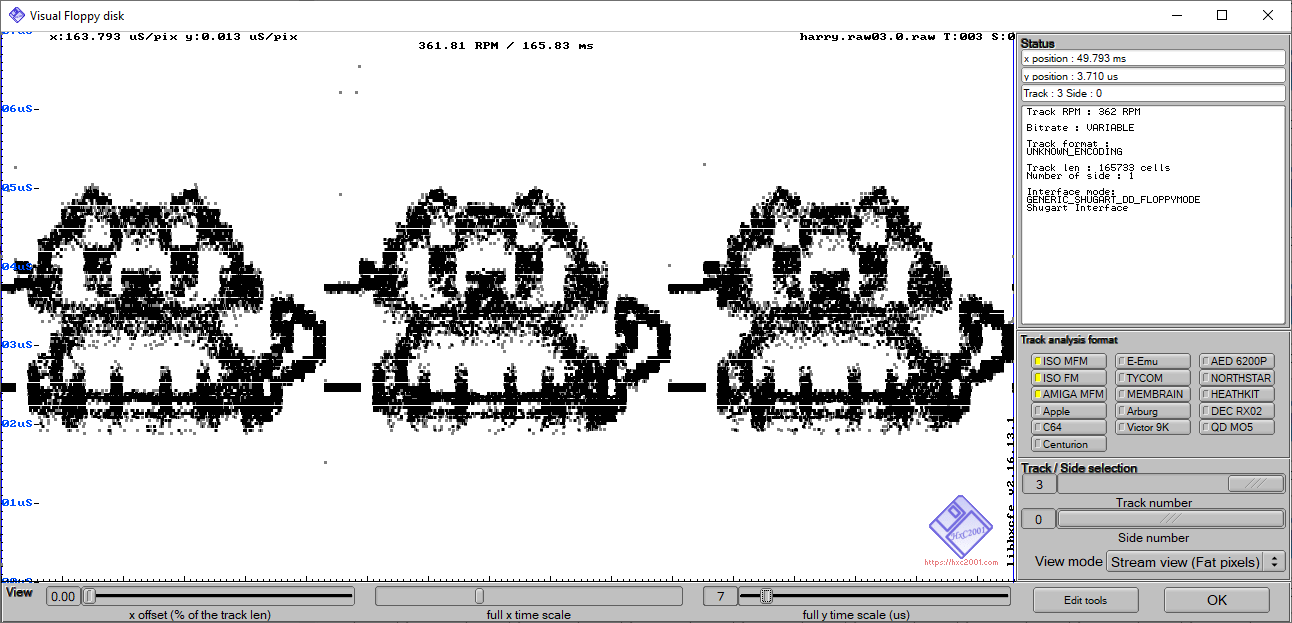

The track timing diagram is essentially a top-down visualization of these pulses, laid out as the disk spins. You’d traditionally use the diagram to check a floppy disk for errors, such as bit shifts or speed fluctuations that could corrupt your data. However, this new tool (h/t Hackaday) is able to “paint” pulses onto the disk so that they line up into a more recognizable image. There’s no real, functional use for doing this – it’s just for fun.

Article continues belowThe process works by treating time as a coordinate for space. A standard diagram will show a vertical axis that represents the time taken between each magnetic pulse. This tool deliberately mis-times these flux transitions to more precisely control how each dot appears on the graph. By stacking these pulses across the disk’s circular tracks, pbm2track scans an existing portable bitmap image (saved in the pbm file format) into the magnetic field itself, turning the magnetic signatures into “fluxcels” that align thousands of pulses to recreate your pixel image, hidden on top of the disk.

pbm2track is able to create a virtual track timing diagram without a disk, but if you have a spare floppy, you can write it directly. However, developer dbalsom doesn’t offer any guarantees that it will work, especially if your hardware “doesn’t like writing raw, unformatted flux nonsense,” and recommends using an open-source floppy controller like a GreazeWeazle for the best results. While the developer has achieved it themselves by printing images of a cat to a disk, it isn’t perfect, with a slight “smear” effect showing that more work might be needed to perfect the process.

This is certainly a novel way to repurpose an old floppy disk, and might prove to be a fun, technical challenge. If you fancy saving pixel images of your pets or loved ones to an old floppy, however, you might find it easier just to save it onto the disk as a traditional file – as long as it’s under 1.44 MB, of course.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our latest news, analysis, & reviews in your feeds.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Ben Stockton is a deals writer at Tom’s Hardware. He's been writing about technology since 2018, with bylines at PCGamesN, How-To Geek, and Tom’s Guide, among others. When he’s not hunting down the best bargains, he’s busy tinkering with his homelab or watching old Star Trek episodes.

-

hwertz As a long time user of floppies on the Atari 8-bit, Laser 128 (Apple II clone, although I didn't use it much since the Atari was better), and both 5 1/4 and 3.5" floppies on PC, I've never heard of a track timing diagram. The description describes it well enough put it certainly wasn't a standard thing on the systems I ran.Reply

This project's still pretty cool though!