37 years ago this week, the Morris worm infected 10% of the Internet within 24 hours — worm slithered out and sparked a new era in cybersecurity

The Internet contracted worms a year before the World Wide Web was even a thing.

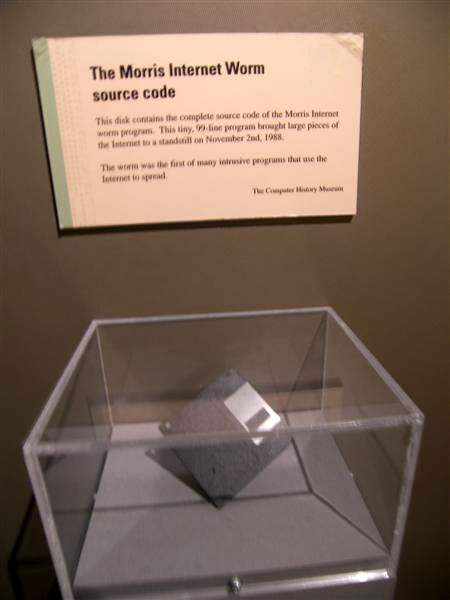

This week in 1988, Cornell graduate student Robert Tappan Morris unleashed his eponymous worm upon the Internet. The wave of infections grew to 10% of the entire Internet within 24 hours, causing astronomically expensive damage for the time. However, the pioneering Morris worm malware wasn’t made with malice, says an FBI retrospective on the “programming error.” It was designed to gauge the size of the Internet, resulting in a classic case of unintended consequences.

Morris worm dissection

Known to be something of a prankster, Morris must have felt some foreboding about releasing his ‘innocent’ program into the wild. Evidence of this comes from his release method. “He released it by hacking into an MIT computer from his Cornell terminal in Ithaca, New York,” according to the FBI.

The Morris worm was written in C and targeted BSD UNIX systems, like VAX and Sun-3 machines. Specifically, the FBI writes, it “exploited a backdoor in the Internet’s electronic mail system and a bug in the ‘finger’ program that identified network users.” In contrast to computer viruses, the worm Morris had devised had no need of a host program, but could self-replicate and spread autonomously.

Thankfully, the Morris worm wasn’t written to cause damage to files. Due to those unintended consequences, though, it precipitated massive slowdowns, and messaging delays and system crashes were common symptoms. It became a computer news sensation in the worst possible way. Just to get rid of the worm in a timely fashion, some institutions ended up wiping complete systems and unplugging networks for as long as a week.

Among the Morris worm's casualties were prestigious institutions such as Berkeley, Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, Johns Hopkins, NASA, and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Whodunit?

Experts worked hard to find a fix, and while they did so, the question of who was behind the worm came to the fore. Understandably, whoever created and unleashed this worm needed to feel some consequences, and thus, the FBI was brought in.

Apparently, Morris sought to anonymously explain and apologize for the worm, but an inadvertent slip of his initials by a friend landed Morris in it.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

FBI interviews and computer file analysis would subsequently confirm Morris was the culprit. He was indicted under the rather freshly inked Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986. After a court appearance for his misdemeanors in 1989, Morris ended up not with jail time, but with a fine, probation, and 400 hours of community service to complete.

Computer worms have been around longer than the World Wide Web

Back in November 1988, the Internet bore little resemblance to what it is today. For example, the World Wide Web (WWW) wasn’t even a thing. Though the WWW would soon form the core experience for the first tide of surfers in the 90s.

At the time, the Internet’s backbone was the NSFNET, the recent successor to ARPANET. Its purpose was mostly to expand the prior backbone’s reach beyond military and defense institutions, and it more broadly embraced academia. While we are here, it is worth mentioning that NSFNET was decommissioned in 1995, and succeeded by the commercial Internet, which emerged in the 1990s off the back of private ISPs and commercial backbones.

So, when we talk about 10% of the Internet being paralyzed by the Morris Worm, contemporary estimates are that about 6,000 of the approximately 60,000 connected systems were infected and impacted. Moreover, when we highlighted the potentially massive costs of this first worm propagating, estimates range from $100,000 to millions of dollars.

Computer worms have remained a scary phenomenon in recent times. For example, we reported on the first-generation AI worm, the Morris II generative AI worm, last year.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our latest news, analysis, & reviews in your feeds.

Mark Tyson is a news editor at Tom's Hardware. He enjoys covering the full breadth of PC tech; from business and semiconductor design to products approaching the edge of reason.

-

sb5k I was working at DEC when the worm slithered its way across the Internet, as part of an engineering team. I also helped manage our Ultrix systems; our IT department knew VMS only.Reply

I don't remember which CPU was in our systems, but the worm was not able to run on our systems, but I did find it dropped in them. -

Gaston404 I completely disagree with the tone of the article. Depicting this as an accident without consequences and limited effect is simply incorrect.Reply

Back then as a part time job I managed some of the traffic routing through Washington DC. Mail relays were shutdown and backed up queues were spooked off to tape. By today’s standards the volume of traffic may seem trivial but when many of these links ran at 56kbps or less. It was a mess. The main way administrators communicated with each other was email. This also affected collaboration between University researchers and access to the NSF super computer centers.

At the time rumors maintained that Morris used exploits that he learned from his father who had a consulting agreement with the NSA. So if this is true there is a certain level of non-originality.

On one hand stronger persecution may have reduced follow on internet crime. On the other hand the fragility demonstrated by this crime, resulted in the creation of procedures to deal with outages. If anything the naive sense of trusted collaboration that pervaded the Internet started to fade. -

derekullo In 9 years, Tiktok has infected over 90% of the internet!Reply

Much slower but also much more insidious! -

DS426 Reply

The next big social media craze is probably just around the corner. I shutter to think how ludicrous it will be.derekullo said:In 9 years, Tiktok has infected over 90% of the internet!

Much slower but also much more insidious! -

Spuwho Yes, I was around for the Morris Worm. Yes it caused a bunch of inconvenience for a lot of sysadmins of the era. But it kicked off a recognition that many of these systems and their connected networks were woefully insecure and easily confronted with actors of any intent.Reply

While the NORAD hacks got the military going on securing their systems, the Morris Worm forced the Universities and Research companies to do the same. Up to then the worse thing NSFNet users were doing was passing bootleg Star Trek movie scripts. -

cuvtixo Reply

You're trying to have it both ways. I think it naive to think "stronger" prosecution would have reduced crime. I could reference crime statistics on how harsher sentences don't result in more than a small bump, but especially in this case, I think it would have discouraged students from learning about computer networks at all, not so much discourage criminals. To strongly prosecute is what authoritarian regimes do, and the stifling of technology and lack of innovation is seen In those. I might even argue the Morris Worm encouraged growth, experimentation, and as you say, resulted in procedures to deal with outages. Punishing Morris more would not have helped with any of that. It would only scratch a sadistic itch. And maybe encourage another Aaron Swartz situation.Gaston404 said:On one hand stronger persecution may have reduced follow on internet crime. On the other hand the fragility demonstrated by this crime, resulted in the creation of procedures to deal with outages.