The Stout Owl: How I Built the Ultimate Noctua G2 PC

This PC eats opulence for breakfast

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For as long as I can remember, I’ve dreamt of building my own PC case. Not to mass produce one and bring it to market, but to prove to myself that, as a former case reviewer, I also have what it takes to design and build a chassis myself. Except, the right opportunity never presented itself. So, when the opportunity arose to build a ‘Showstopper build’ for Tom’s Hardware Premium, I wanted to do something special.

Noctua recently also celebrated its 20th anniversary, so I thought it would be fitting to commemorate the occasion by hand-crafting a PC case made out of wood, kitted out with the best parts Noctua could offer. How hard could it be, right?

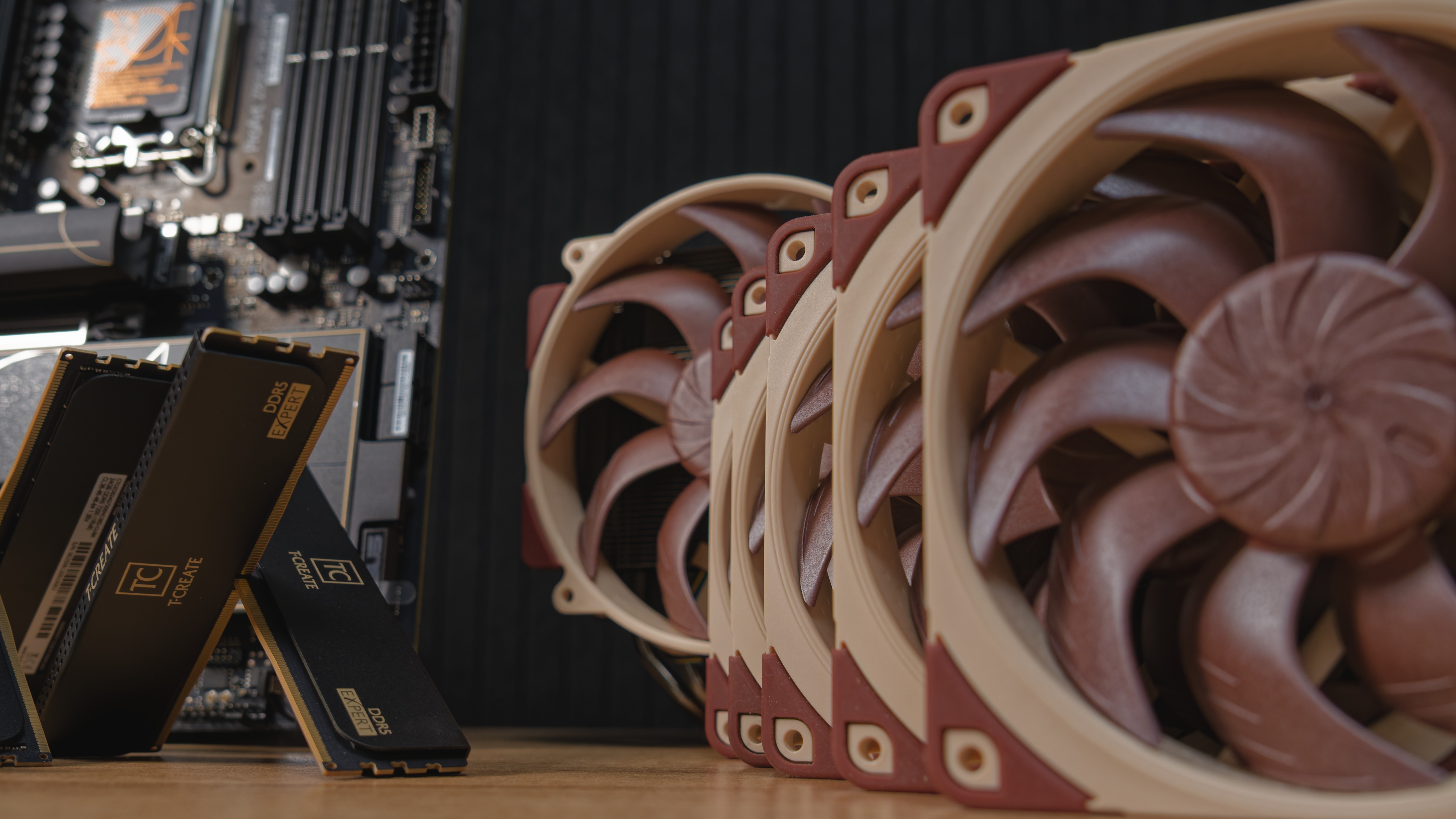

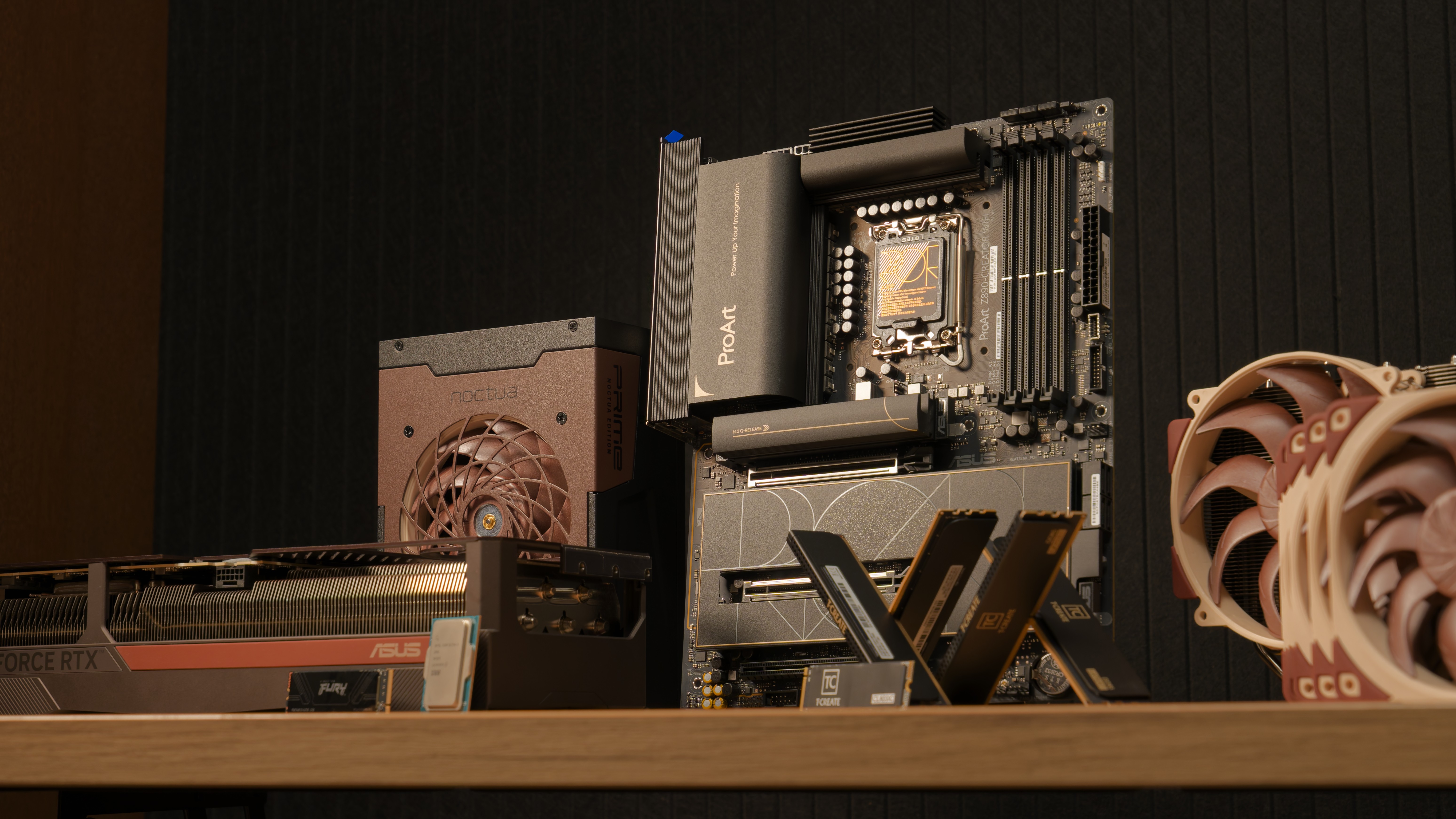

For this build, we feature an Asus Z890-Creator motherboard, Intel Core Ultra 285K processor, 96 GB of Team Group T-Create memory, and two 2 TB SSDs: one from Team Group and another from Kingston. Noctua also supplied an ample laundry list of fans and parts, including its mighty NH-D15 G2 cooler, a power supply, a handful of G2 spinners, and of course, the pièce de résistance: the Asus x Noctua GeForce RTX 5080.

Before we move forward, we've also produced a handy build video, which will cover many elements of this article, as a companion piece to the build. Follow us on our journey, including all of the trials and tribulations of undertaking such a task.

Why build a wooden PC?

Initially, I hadn’t planned on a wooden case for this build. In fact, I aimed to use all off-the-shelf parts, but I’ve been running into a bit of an issue in my quest for a case worthy of these components: It seems like the market for high-end, high-quality ATX cases has dried up a bit – everything has become thin sheet metal and oceans of glass.

Where’s the CNC’d and brushed aluminum? Where are the thought-out layers of acoustic treatment we used to find? Even the best PC cases have mostly become samey-looking boxes that end up looking a bit too anonymous. And while there are efforts to differentiate some in design, none of them spoke to me.

Now, I don’t have the resources at my disposal to build a CNC’d aluminum case (it would also be prohibitively expensive), but it just so happens that Noctua components pair up beautifully with wood, which is down to the iconic brown and beige branding. Now, I’ve been a hobby woodworker for a little while, so why not challenge myself by building a case entirely out of wood? What I found out, after months of hard work, was that it would become the ultimate test of my skills.

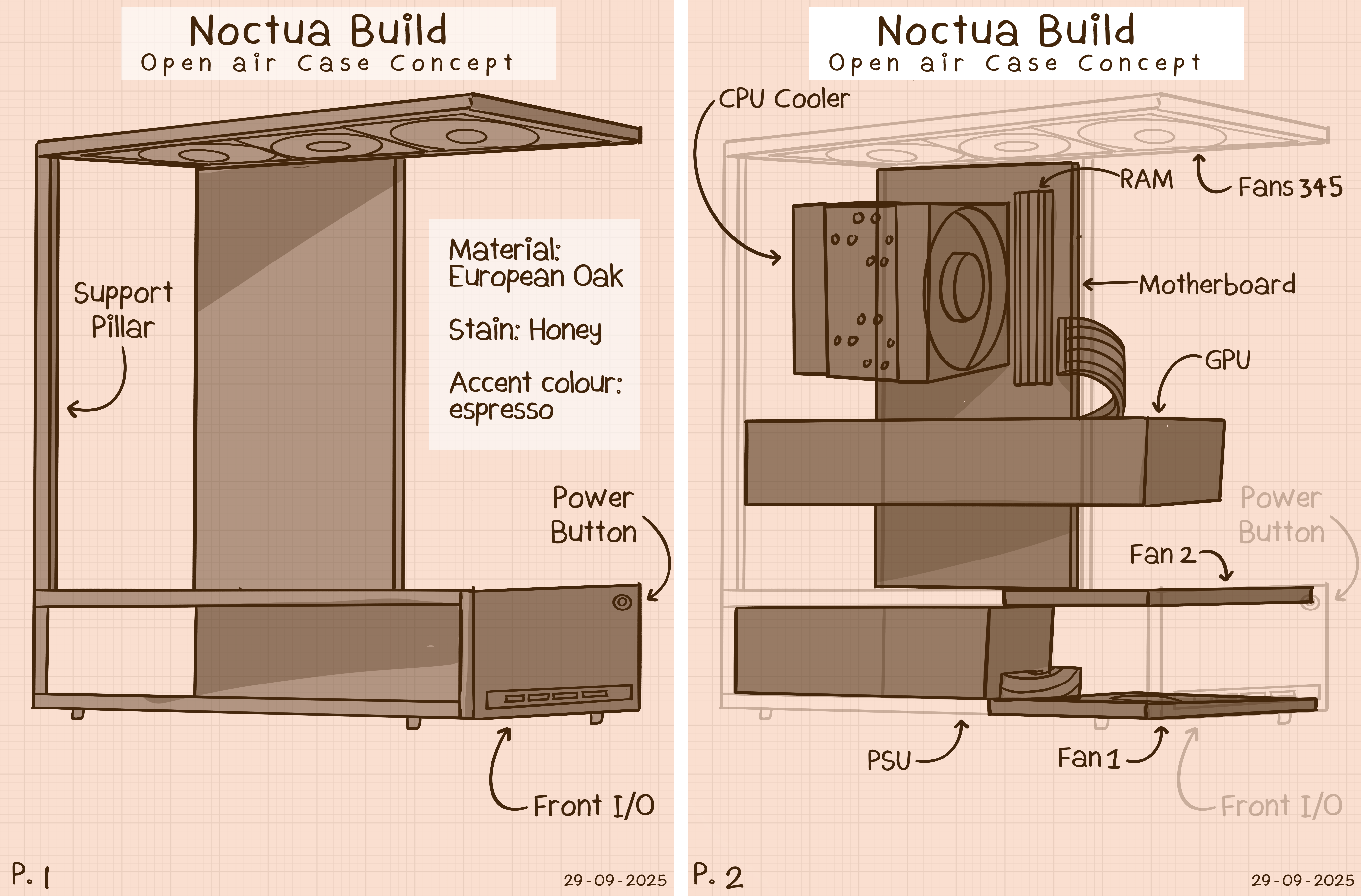

Designing the custom case

Over the last few years, I’ve been rocking an open-air, water-cooled PC – Blue Shift. In this time, I’ve learned that open-air PCs are nothing to be afraid of. It doesn’t seem to gather a ton of dust, it’s easy to clean, and my cats have zero interest in poking around the inside. This may be different for folks with children, but for me, an open-air case came with basically no downsides.

Most recently, I did a build in Phanteks’ Evolv X2, and it has some design elements I quite admired. Most notably, the motherboard tray is only as wide as it needs to be, and consequently, a large GPU stretches past the tray, giving it a floating appearance. The same goes for the top radiator mount of that case.

I sketched up a design, but throughout the build, many parts of it changed. For one, I found a much stronger piece of wood to use as the motherboard tray than I anticipated, so I decided to take the floating aspect a step further – notice how the support bracket on the left of the sketch is missing in the final piece?

From the start, I had a few goals in mind. It was going to follow a standard-ish ATX tower layout. It would be open-air, be 100% air-cooled, and no taller than it needs to be. Because the PSU chamber would be going around the spine holding the motherboard, it would also be somewhat wide. Quiet, short, well-set, and powerful: The Stout Owl.

Component selection

With the calm Noctua theme, I didn’t feel it was fitting to build a system aimed purely at gaming – it had to be quiet and efficient, more of a workstation. With that in mind, the basis for the system became the Intel Core Ultra 9 285K, as this CPU offers fantastic multithreaded performance and extremely low idle power consumption.

This chip was placed into the Asus Z890-Creator WiFi motherboard and paired with two 48 GB kits of Team Group T-Create 7200-MHz CUDIMM memory, for a total memory pool of 96 GB, across four modules. I am aware that for performance optimization, it’s better to stick to using only two DIMMs, but visually, this doesn’t work for me – and this is a build that’s all about the aesthetics.

Disclaimer: These memory kits were acquired before the DRAM crisis. In today’s market, I would not opt for this memory configuration due to the cost.

For storage, I picked a 2 TB Kingston Renegade G5 PCIe 5.0 SSD as the main system drive, with the Team Group T-Create C47 series Classic 2TB PCIe 4.0 drive for additional capacity.

Of course, from Noctua’s lineup, we picked the Asus x Noctua RTX 5080, the mighty NH-D15 G2 as the CPU cooler, the Seasonic x Noctua Prime 1600W Power Supply, and five NF-A12x25 G2 fans, two of which as part of a Sx2-PP set for speed offsets to avoid harmonics in the top panel.

For the USB ports, incorporated a Fractal Design 10 Gbps USB C Model D cable, along with a DeLock USB 3.0 Type-A internal cable to round things out.

Parts List

Processor | Intel Core Ultra 9 285K | $ 519.00 |

Graphics Card | Asus x Noctua RTX 5080 | $ 1799 |

Motherboard | Asus Z890-Creator WiFi | $ 467 |

Memory | (2x) Team Group T-Create Expert DDR5-7200 CL36 | $ 1129.98 |

CPU Cooler | Noctua NH-D15 G2 | $ 179.95 |

Power Supply | Seasonic x Noctua Prime TX-1600 | $ 654 |

SSD 1 | Kingston Renegade G5 2TB | $ 392 |

SSD 2 | Team-Group T-Create C47 2TB | $ 235.99 |

Fans | 3x NF-A12x25 G2 1x NF-A12x25 G2 Sx2-PP | $ 225.49 |

RGB Controller | Phanteks NexLinq V2 | n/a |

RGB Strips | 2x Phanteks Neon M5 1x Phanteks Neon M1 | n/a |

Custom Wooden Case | Row 11 - Cell 1 | I don’t want to know |

Total | Row 12 - Cell 1 | $ 5632.41 |

Materials Selection

For the case, I decided to work with European oak, because American oak has a totally different appearance. I also live in the Netherlands, so I could not get my hands on American Oak, even if I wanted to.

I purchased a pair of 18mm thick oak panels to build many of the case’s pieces with, along with a ‘wall shelf’ that has a tree trunk edge on one side. I loved the appearance of this “live edge,” as it’s often called, and the 40mm thickness. This would give me plenty of strength to function as the spine for the PC, even with cable management channels gutted out of it.

In addition to the oak pieces, I also grabbed a strip of meranti hardwood, which would function as the splines in the joints for added strength. I wanted to avoid materials like plywood and acrylic, as I find them too soft and fragile – they would experience much harder wear and tear over time.

The tools I have at my disposal

Having completed a full DIY home renovation, I have a fair number of tools at my disposal. These include basics such as a circular saw, a jigsaw, a handful of chisels, a drill, a cheap soldering iron, and a palm sander.

I also have a miter saw, as one of my past projects was a herringbone floor, where everything had to be cut at 45-degree angles. This proved to be one of the two most valuable tools in this project.

The other key tool for this project was the router. For this project, I purchased the Makita DRT50Z. I was already invested in the LXT battery ecosystem, and it is one of my best powertool purchases to date – this build would not have been the same without it, as it let me route the cable gutters and cavities at the back of the system, cut the holes for the USB ports, the grooves for the illumination, and trim all the edges to shape. In the end, I must have spent 50+ hours using the router, and although a CNC machine would have saved me a lot of time, it’s far beyond my budget and would take away from the handmade aesthetic.

I also used a basic collapsible workbench so that I could work outside, and decided to finally invest in an orbital sander, along with a heap of little accessories like drill bits, various router bits, sandpaper, extra clamps, tin, and so much more.

While not strictly necessary, my DA polisher also came in handy during the final finishing process.

For dust collection, I used a cheap Philips household vacuum with a custom (homemade) fine particle filter. As an apartment dweller, I do not have the space for a proper shop-vac, and despite the hell I’ve put this household vacuum through over the years, it’s still somehow functional. Masks and safety glasses were used as an extra safety measure, along with hearing protection.

Niels Broekhuijsen is a Contributing Writer for Tom's Hardware US. He reviews cases, water cooling and pc builds.