The Stout Owl: How I Built the Ultimate Noctua G2 PC

This PC eats opulence for breakfast

To test the performance of this PC, I started by changing a few system parameters. For Showstopper builds like this one, the aim is maximum performance within thermal or power limits, whichever comes first.

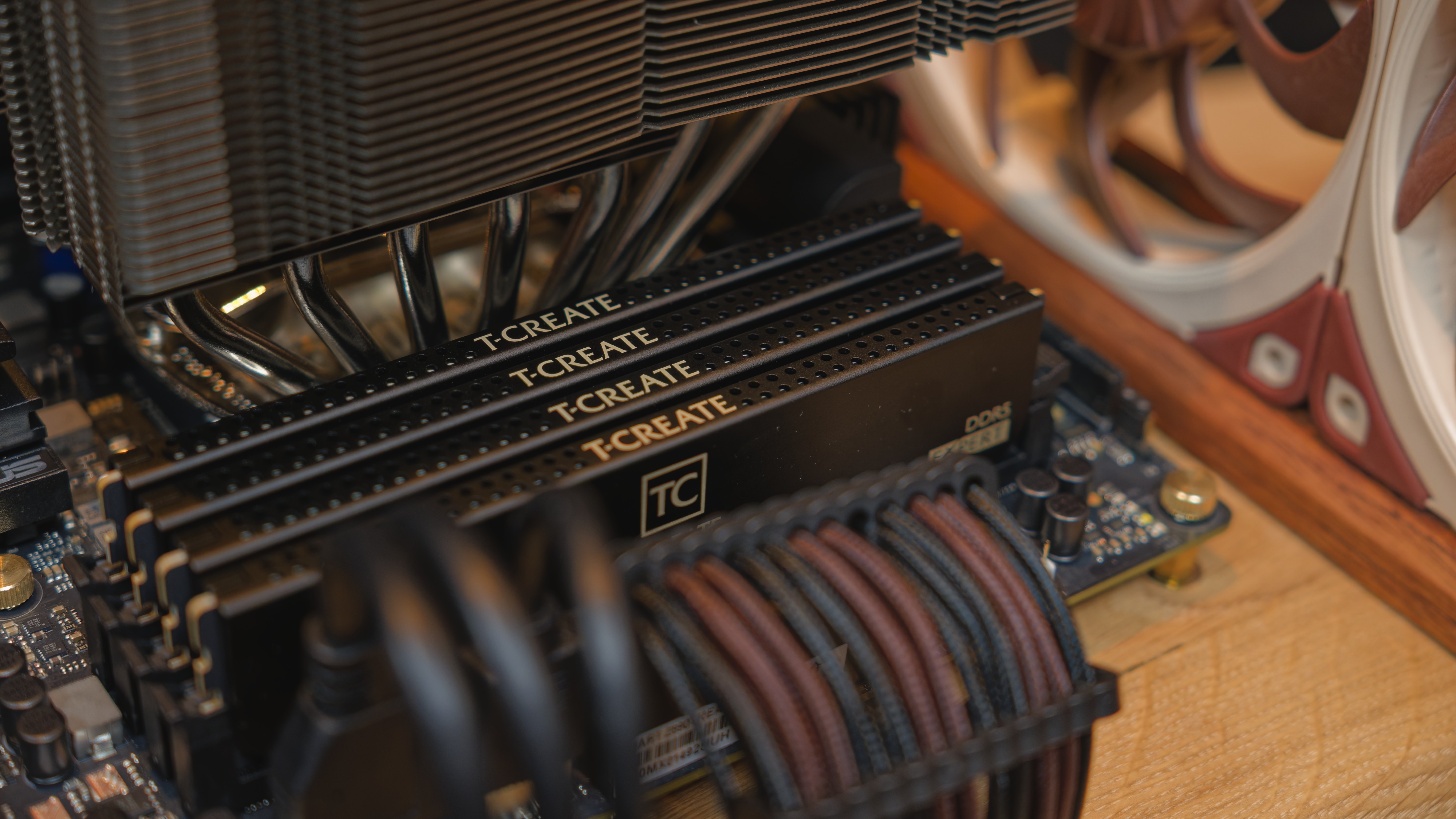

For starters, the memory was set to the XMP-II profile, where it takes on the voltage, frequency, and timings Team Group intends the kits to run at. It’s worth noting that despite using four modules from two identical kits, I had no problem running the XMP-II profile at 7200 MHz with CL36 timings.

This is a testament to both CUDIMM technology and Team Group’s binning for these modules. However, I must note that there was a luck factor: Running four modules at their intended frequency and timings, especially if they only come in a kit of two, even with CUDIMMs is not a guarantee, and depending on your CPUs IMC, you may not get such luck. Obtaining the memory with the intention to run it this way was a gamble, but it paid off handsomely.

From there, I set up a fan curve that suits the system. Personally, I find idle temperatures for both the GPU and CPU under 50 degrees C acceptable. Under load, I’m willing to let a CPU cook up to 5 degrees C below its thermal limit during an extended Prime95 run – real life scenarios never offer such loads anyway, but 5 degrees under the thermal cutoff under synthetic stress is a good figure to strive for given that in practice, it would never come close to that anyway.

As such, for this build specifically, I set the CPU fan up to run at 10% duty up to 50 degrees C, ramp up to 60% approaching 70 degrees, then stay at 60% until 90 degrees C is reached. From 90 to 100 degrees C, the curve ramps up to 100%. The reason for this plateau at 60% is to avoid unstable fanspeeds during extended real-world loads. And unless you’re running a synthetic test, the CPU fan should practically never exceed 60% duty.

I allowed 10-15 minutes for things to saturate, and then measured temperatures over the course of one minute. It ended up at 98 degrees C with this fan curve, hitting that sweet spot, and I did not need to lower the power limit, nor did I have to undervolt the 285K. I could have, but was happy with the result, given that real-life workloads only lead to temperatures around the mid-70s.

For the GPU, temperatures are generally much lower, as there is no integrated heatspreader at play – the cooler makes direct contact with the GPU die. The Asus x Noctua RTX 5080 has a standard power limit at 360 W, but I was able to max out the power limit to 450 W and raise the GPU clocks to a zippy 3,172 MHz under boost. Despite leaving the graphics card’s BIOS switch in quiet mode, it still kept the GPU at no more than 63 degrees C, and everything was running perfectly stable, so I was happy and left it at that.

The PSU was not run in passive mode, as the fan opening is facing downwards, which limits convection, making passive mode less than ideal.

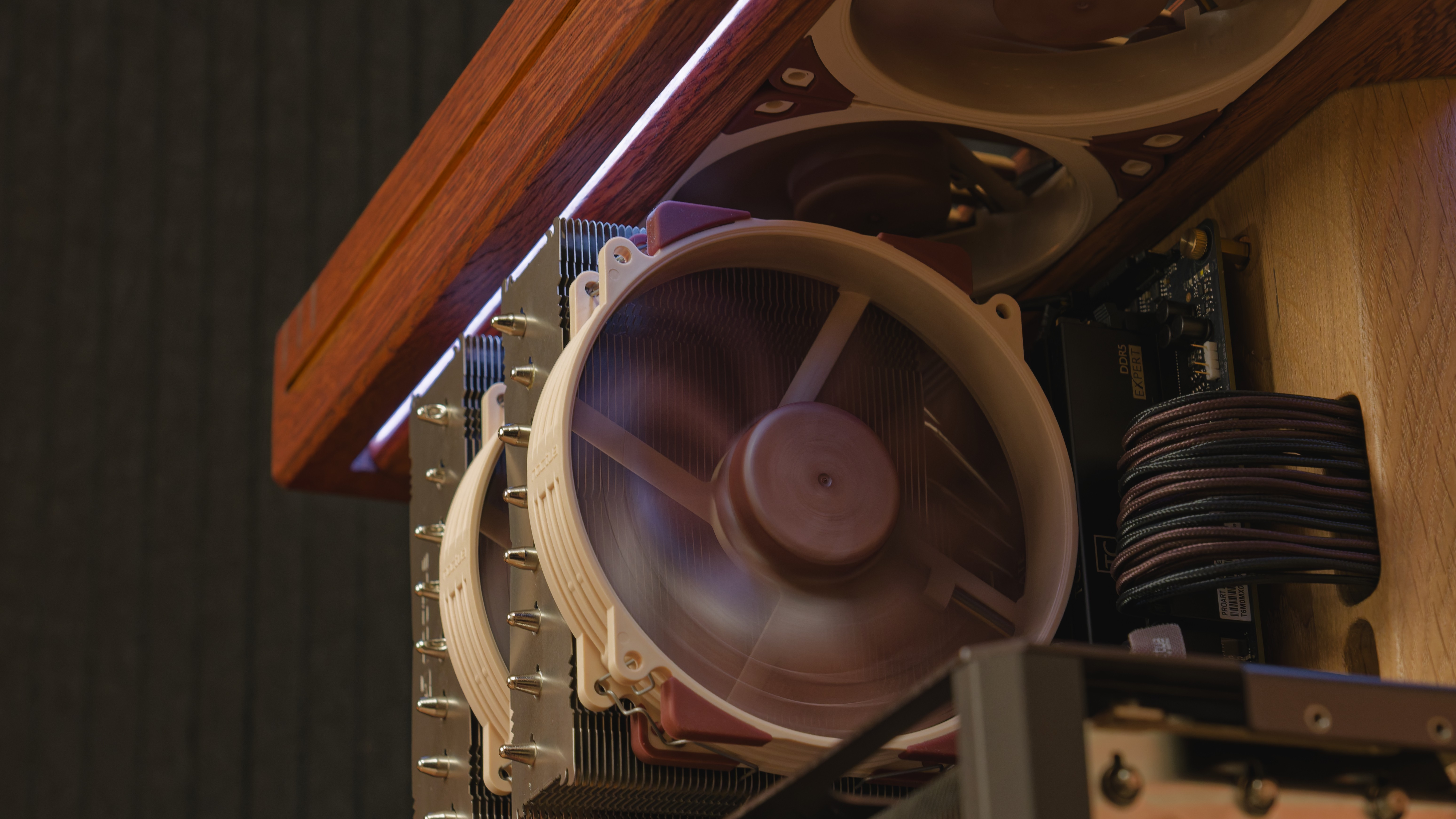

So, why the case fans?

So, the case fans. I’ve asked myself the question why I’m using them at all numerous times. I chose not to run them passively, as I don’t want any heat accumulating in any of the cavities of the wooden chassis. The case fans were, however, all limited to a maximum 50% duty because let’s be real: It’s an open-air PC – it could probably do without the case fans altogether and just let convection handle the rest, but the aesthetics of a Noctua build would never be complete without the iconic fans.

Luckily, the fans are nearly inaudible while the system is powered on, even at 50% duty, and let’s face it: We’re pushing 800 watts through this system, and the case is made from the same stuff we throw in our fireplaces.

Besides, without the fans, I wouldn’t have had an excuse to make the gorgeous vents throughout the case. By that logic, I could also have done without the top panel altogether. And the PSU chamber too – just strap everything to a single panel with some feet to hold it upright. Right?

That would be no fun! We get case fans in an open-air case. Deal with it.

Performance testing

The tests below are run until thermals stabilize, the temperatures and power levels are recorded for 1 minute, from which their average is calculated.

Test | Duration/Score | CPU Temp | GPU Temp | dBA | System Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sleep | Row 0 - Cell 1 | Row 0 - Cell 2 | Row 0 - Cell 3 | 33.2 | 4 W |

Light Browsing | Row 1 - Cell 1 | 46 | 38.4 | 33.2 | 102 W |

DXO-Export | 15:57 | 73 | 40.6 | 33.7 | 313 W |

3DMark Speedway | 9387 | 65 | 57.8 | 34.2 | 472 W |

Cyberpunk | 103 FPS | 72 | 57.3 | 33.8 | 483 W |

Prime95+Furmark | Row 5 - Cell 1 | 98 | 63 | 42.5 | 798 W |

All Fans Full | Row 6 - Cell 1 | 96 | 58.8 | 49.3 | 797 W |

In due time, as I collect data on more builds, I will make charts to compare systems to one another. But for now, we can draw some clear conclusions from the data we have about this build specifically.

It uses just 4 W in sleep mode. When browsing with a few programs, MS Word, and a few tabs open, system power hovers around 100 W, and noise levels are indistinguishable from the ambient levels in the room. Truly, the fans may look like they’re spinning, and sticking your finger in would confirm that, but your ears wouldn’t pick up a thing – or at least mine don’t.

During a 1000-shot DXO PhotoLab export, where each image has a handful of effects applied, including DeepPrime 3 AI Denoising, the system consumed an average 313 watts, and barely broke the ambient noise floor by just 0.5 dBA. DXO Photolab loads up the 285K nicely and also uses the RTX 5080. In fact, as each shot passes through the export, you can hear when it gets handed over to the GPU for the final DeepPrime3 denoising step, because of the very brief light coil whine.

3DMark Speedway put down a tidy score, and so did Cyberpunk 2077. In fact, gaming, despite drawing near 500 watts, at most raises the noise level by 1.0 dBA above the ambient noise floor – a truly astonishing feat, and without a doubt, it’s quieter than custom water cooling. The only perceivable sound is a tiny bit of wind noise and coil whine, the latter of which you can only hear because well… it’s an open-air PC.

Of course, if you load the system up with Prime95 and Furmark at the same time, things get hot, hungry, and noisy. In fact, despite all G2 fans from Noctua, this PC can make quite a ruckus – but it’s totally unnecessary, and I honestly don’t know why anyone would choose to do this other than for kicks.

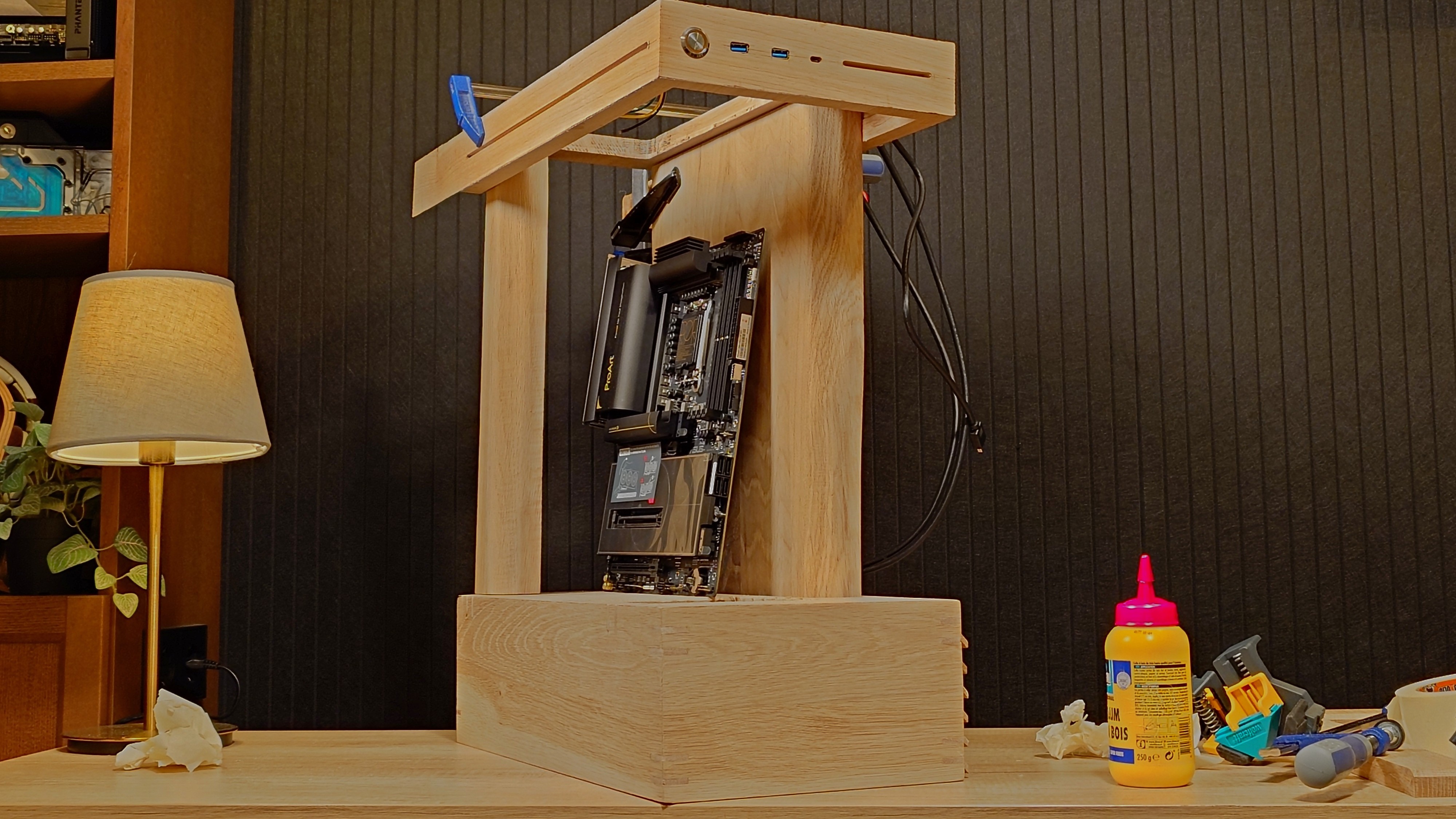

This took a very, very long time

Getting the basic shape of the case built was a breeze. However, after building the PSU chamber and bolting the spine to it, I needed the motherboard on hand to route out the cable management on the back of the case’s spine. Then, the motherboard got stuck in customs, and there wasn’t much I could do in the meantime.

However, it turns out, once I got the motherboard, the adventure had only just started. Building the basic frame of the case only took about a week – half the time I had allotted to building the entire case.

It’s the details that got me. The vents took me about a week and a half, spread out across the project. The spine probably took just as long. The top panel, though not very big, contains three LED strips, a power button that’s internally very challenging to find the space for, three USB ports, an RGB controller, 21 flaps for the vents and three 120mm fans. That top panel took the better part of two weeks to figure out.

I’ve told the story in this article in a somewhat orderly fashion, but the reality is that all these pieces are interconnected somehow, and there was a ton of back-and-forth to get everything to fit together.

Even building the two GPU support brackets, though they may look like a simple L and a nub, took 10 hours to build, because I also needed to figure out how to attach them to the spine, route those holes out, bevel them, water-pop and sand them, and apply the finish to not only the two support brackets, but also the adjustments on the spine where I had cut through the finish applied earlier.

When all was said and done, I spent about a week sanding and finishing the entire project, and only then could I install the system into it.

Thankfully, the system is air-cooled, so the installation was a breeze in comparison to the rest of the project.

Reflecting on the saga

Building The Stout Owl has been an adventure. It was easy imagining how I’d build a wooden case in a week, maybe two, but in practice, this is a project that by the time I finished, I had poured somewhere between 5 and 600 hours into if you include all the planning that came in the months before the case building even started.

Of course, I could have saved myself a lot of headache by fully designing the system beforehand and handing the CAD drawings over to a company to CNC the pieces for me. It may even have been cheaper despite outsourcing, but I don’t regret not doing so. The Stout Owl is entirely handmade with nothing but a few powertools, not a single one of which cost more than $250 – this is something achievable in a small apartment, and it doesn’t require multiple-thousands of dollars worth of equipment, provided you have the time and patience.

Moreover, because I started out with only a simple sketch, the final design is something that evolved throughout the build process. Initially, I hadn’t planned on many of the complexities the final piece has – but the more time I sank into it, the more determined I became to perfect every last piece. For every skill I learned along the way, I went back to earlier parts of the project to improve on them.

Examples of these kinds of evolution are the vents, which despite their rough start turned out far more beautiful than I could have imagined – and even though almost nobody will ever see it, I love the unique touch of the letters and numbers being stamped into them to accommodate for the fact that I did an imperfect job flattening the slab I made their holders from.

In that same line of thought, the levitating GPU mount is something I would never have come up with had I not spent as much time with my hands on the workpiece and evolving the design as I went about building The Stout Owl.

Now that it’s over, I’m going to be taking a long weekend, and then I’ll get back to the “regular” builds for the inspiring creativity series.

Special Thanks

This build was made possible thanks to Noctua, Team Group, Kingston, Phanteks, Asus, and Intel, Tom’s Hardware Premium subscribers, and my partner.

Others, whose names I don’t know, also played key roles – folks I met at the hardware store, a parquet shop for the finish – people who helped me with advice along the way.

Parts List

Processor | $ 519.00 | |

Graphics Card | $ 1799 | |

Motherboard | $ 467 | |

Memory | $ 1129.98 | |

CPU Cooler | $ 179.95 | |

Power Supply | $ 654 | |

SSD 1 | $ 392 | |

SSD 2 | $ 235.99 | |

Fans | $ 225.49 | |

RGB Controller | Phanteks NexLinq V2 | n/a |

RGB Strips | 2x Phanteks Neon M5 1x Phanteks Neon M1 | n/a |

Custom Wooden Case | Row 11 - Cell 1 | I don’t want to know |

Total | Row 12 - Cell 1 | $ 5632.41 |

Current page: System Setup, Fan Curves, Power Limits and Testing

Prev Page Fitting the PC to the CaseNiels Broekhuijsen is a Contributing Writer for Tom's Hardware US. He reviews cases, water cooling and pc builds.