Jensen Huang discusses the economics of inference, power delivery, and more at CES 2026 press Q&A session — 'You sell a chip one time, but when you build software, you maintain it forever'

Developing chips for AI data centers is a complicated business.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang spoke at Nvidia's CES 2026 keynote, the conversation stretched across Rubin, power delivery, inference economics, open models, and more. Following this, Tom's Hardware had the opportunity to sit down and attend a press Q&A session with Huang himself in Las Vegas, Nevada.

While we can't share the transcript in its entirety, we've drilled down on some of Huang's most important statements from the session itself, with some parts edited for flow and clarity. As a whole, it's recommended that you first familiarize yourself with the topics announced at Nvidia's CES 2026 keynote before diving headfirst into our highlights of the following Q&A session, which will reference parts of what Huang discussed onstage.

Huang’s answers during the Q&A helped to clarify how Nvidia is approaching the next phase of large-scale AI deployment, with a consistent emphasis on keeping systems productive once they are installed. Those of you who remember our previous Jensen Huang Computex Q&A will recall the CEO's grand vision for a 50-year plan for deploying AI infrastructure.

Nvidia is designing for continuous inference workloads, constrained power environments, and platforms that must remain useful as models and deployment patterns change. Other comments also include references to SRAM vs HBM deployment at an additional Q&A for analysts. Those priorities in flexibility explain recent architectural choices around serviceability, power smoothing, unified software stacks, and support for open models, and they help to paint a picture of how Nvidia is thinking about scaling AI infrastructure beyond the initial buildout phase we’re seeing unfold right now.

Designing around uptime and failure

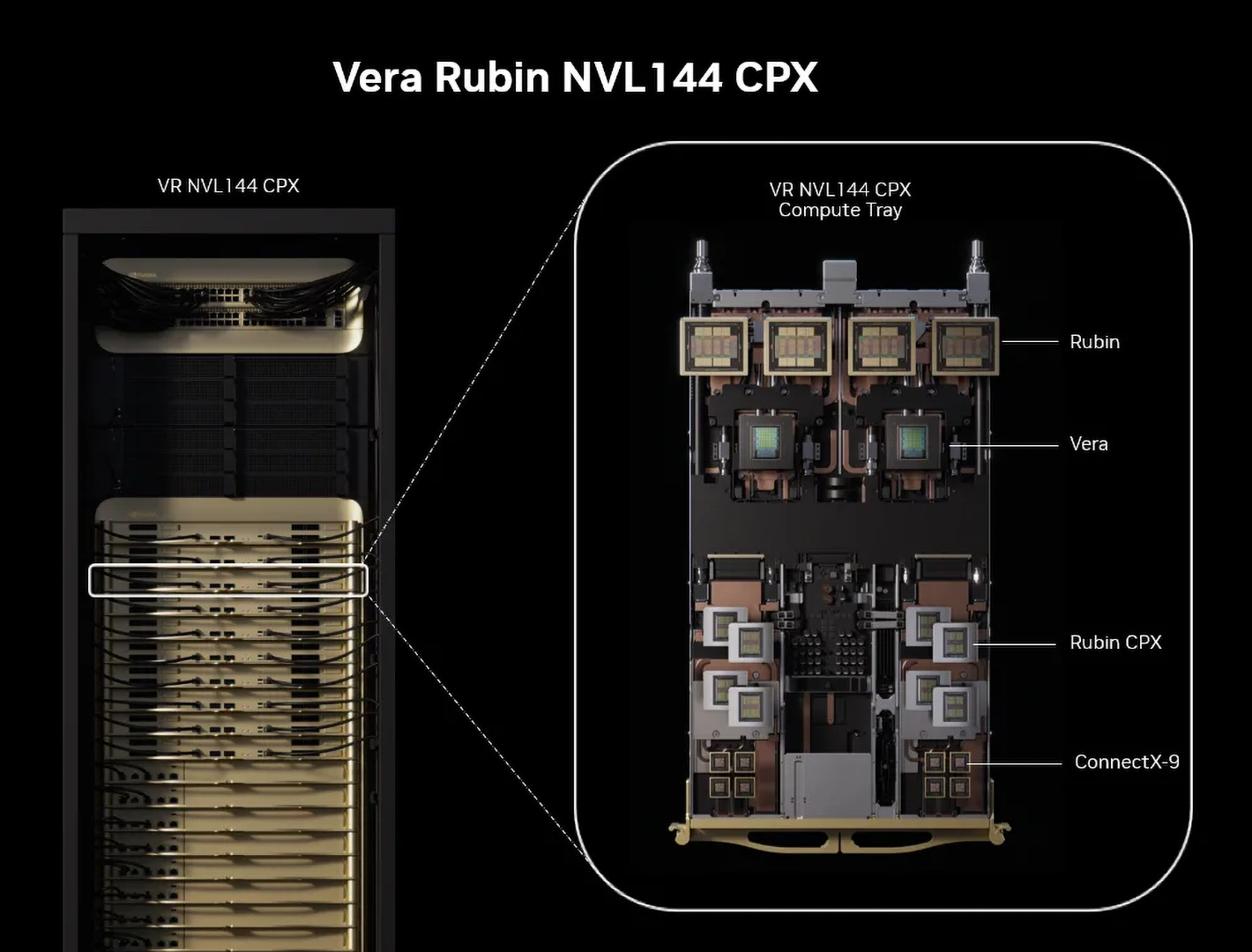

The most consistent theme running through the Q&A was Nvidia’s focus on keeping systems productive under real-world conditions, with Huang spending the lion’s share of the time discussing downtime, serviceability, and maintenance. That’s quite evident in how Nvidia is positioning its upcoming Vera Rubin platform.

“Imagine today we have a Grace Blackwell 200 or 300. It has 18 nodes, 72 GPUs, and an NVLink 72 with nine switch trays. If there’s ever an issue with any of the cables or switches, or if the links aren’t as robust as we want them to be, or even if semiconductor fatigue happens over time, you eventually want to replace something,” Huang said.

Rather than parroting performance metrics, Huang repeatedly described the economic impact of racks going offline and the importance of minimizing disruption when components fail. At the scale Nvidia’s customers now operate, failures are inevitable. GPUs fail, interconnects degrade, and power delivery fluctuates. The question Nvidia is trying to answer is how to prevent those failures from cascading into prolonged outages.

“When we replace something today, we literally take the entire rack down. It goes to zero. That one rack, which costs about $3 million, goes from full utilization to zero and stays down until you replace the NVLink or any of the nodes and bring it back up.”

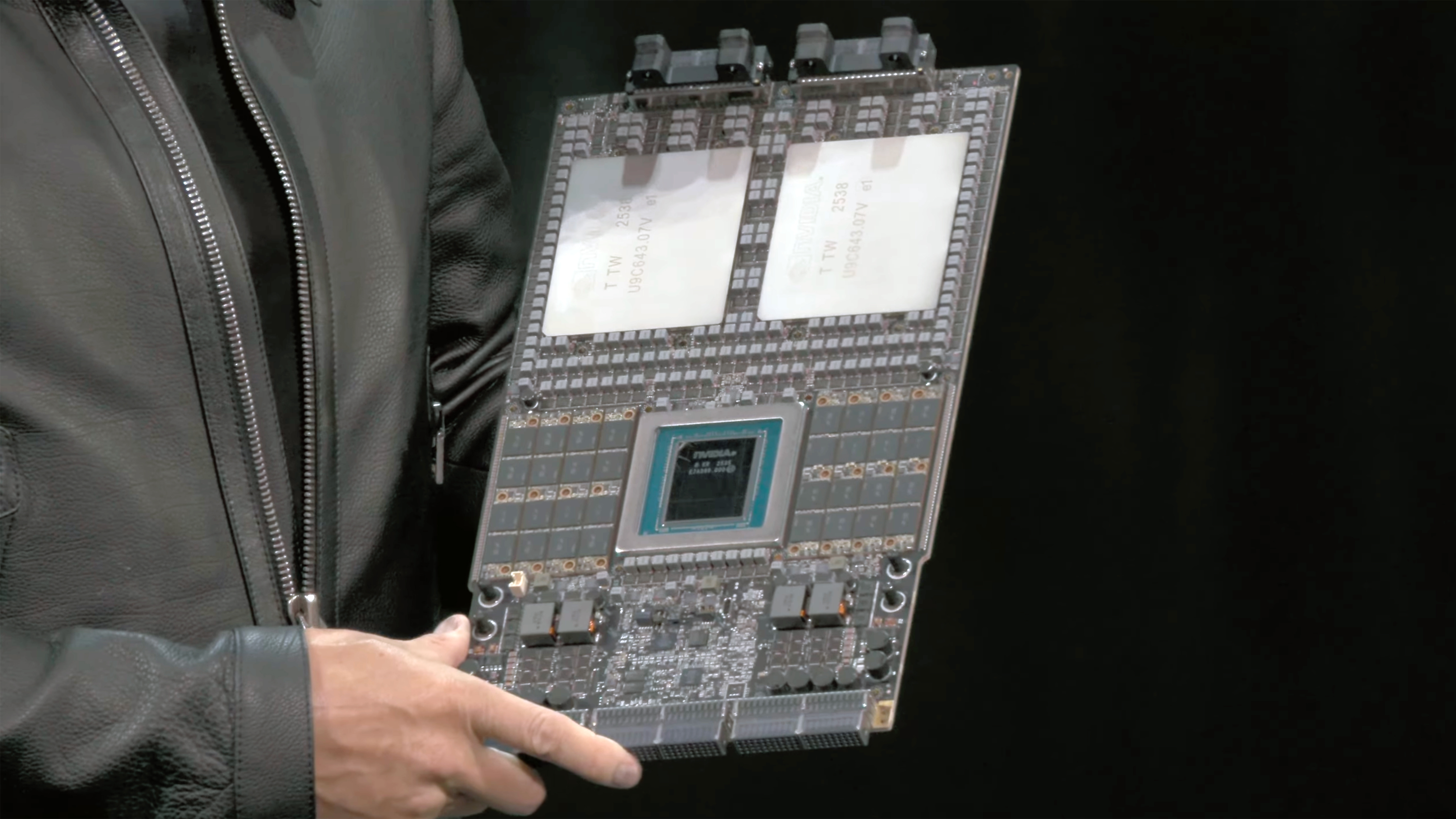

Rubin’s tray-based architecture is designed as the answer to that question. By breaking the rack into modular, serviceable units, Nvidia aims to turn maintenance into a routine operation. The goal is not zero failure — that’s impossible — but fast recovery, with the rest of the system continuing to run while a faulty component is replaced.

“And so today, with Vera Rubin, you literally pull out the NVLink, and you keep on going. If you want to update the software for any link switch, you can update the software while it’s running. That allows us to keep the systems in operation for a longer period of time.”

This emphasis on serviceability also influences how Rubin is assembled and deployed. Faster assembly and standardized trays reduce the amount of time systems spend idle during installation and repair. In a world where racks represent millions of dollars in capital and generate revenue continuously, that idle time is expensive, so Nvidia is understandably treating uptime as a core performance metric on par with throughput.

“Everything comes down to the fact that it used to take two hours to assemble this node. But now, Vera Rubin takes five minutes. Going from two hours to five minutes is completely transformative in our supply chain.”

“The fact that there are no cables, instead of 43 cables, and that it’s 100% liquid-cooled instead of 80% liquid-cooled, makes a huge difference.”

Power delivery is the dominant scaling constraint

Rather than focusing on average power consumption, the discussion kept circling back to instantaneous demand, which is where large-scale AI deployments increasingly run into trouble.

Modern AI systems spike hard, unpredictably, as workloads ramp up and down, particularly during inference bursts. Those short-lived peaks force operators to provision power delivery and cooling for worst-case scenarios, even if those scenarios only occur briefly. This causes stranded capacity across the data center, with infrastructure built to handle peaks that rarely last long enough to justify the expense.

Nvidia’s answer with Rubin is to attack the problem at the system level rather than pushing it upstream to the facility. By managing power behavior inside the rack, Nvidia is attempting to flatten those demand spikes before they hit the broader power distribution system. Considering that each Rubin GPU has a TDP of 1800 Watts, this means coordinating how compute, networking, and memory subsystems draw power so the rack presents a more predictable load profile to the data center. This effectively allows operators to run closer to their sustained power limits instead of designing around transient excursions that otherwise dictate everything from transformer sizing to battery backup.

“When we’re training these models, all the GPUs are working harmoniously, which means at some point they all spike on, or they all spike off. Because of the inductance in the system, that instantaneous current swing is really quite significant. It can be as high as 25%.”

A rack that can deliver slightly lower peak throughput but maintain it consistently is more useful than one that hits higher numbers briefly before power constraints force throttling or downtime. As inference workloads become continuous and revenue-linked, that consistency will be all the more valuable.

The same logic helps explain Nvidia’s continued push toward higher-temperature liquid cooling. Operating at elevated coolant temperatures reduces dependence on chillers, which are among the most power-hungry components in a data center. It also widens the range of environments where these systems can be deployed, particularly in regions where water availability, cooling infrastructure, or grid capacity would otherwise be limiting factors.

“For most data centers, you either overprovision by about 25%, which means you leave 25% of the power stranded, or you put whole banks of batteries in to absorb the shock. Vera Rubin does this with system design and electronics, and that power smoothing lets you run at close to 100% all the time.”

Taken together, the emphasis on power smoothing, load management, and higher-temperature cooling points to a shift in where efficiency gains are coming from; Nvidia is optimizing for predictability, utilization, and infrastructure efficiency. A system that can run near its limits continuously, without forcing the rest of the data center to be overbuilt around it, ultimately delivers more value than one that is faster on paper but constrained by the realities of power delivery.

Inference economics are reshaping Nvidia’s priorities

Huang repeatedly returned to inference as the defining workload for modern AI deployments. Training remains important, but it is episodic, whereas inference runs continuously, generates revenue directly, and exposes every inefficiency in a system. This shift is driving Nvidia away from traditional performance metrics like FLOPS and toward measures tied to output over time. What matters is how many useful tokens a system can generate per watt and per dollar, not how fast it can run a single benchmark.

“Today, [with] tokenomics, you monetize the tokens you generate. If within one data center, with limited power, we can generate more tokens, then your revenues go up. That’s why tokens per watt and tokens per dollar matter in the final analysis.”

While there is growing interest in cheaper memory tiers for inference, Huang also emphasized the long-term cost of fragmenting software ecosystems. Changing memory models may offer short-term savings, but it creates long-term obligations to maintain compatibility as workloads evolve. “Building a chip is expensive,” says Huang, “but the most expensive part of the IT industry is the software layer on top. You sell a chip one time, but when you build software, you maintain it forever.”

Nvidia’s strategy, as articulated by Huang, is to preserve flexibility even at the cost of some theoretical efficiency. AI workloads are changing too quickly for narrowly optimized systems to remain relevant for long. By keeping a unified software and memory model, Nvidia believes it can absorb changes in things like model architecture, context length, and deployment patterns without stranding capacity.

“Instead of optimizing seventeen different stacks, you optimize one stack, and that one stack runs across your entire fleet. When we update the software, the entire tail of AI factories increases in performance,” explained Huang.

The obvious implication of this is that Nvidia is prioritizing durability over specialization. Systems are being designed to handle a wide range of inference workloads over their lifetime rather than excel at a single snapshot in time — “The size of the models is increasing by a factor of ten every year. The tokens being generated are increasing five times a year,” Huang explained, later adding, “If you stay static for two years or three years, that’s just too long considering how fast the technology is moving.”

Open models are inflating demand

Huang also addressed the rise of open models and discussed how he sees them as a growing contributor to inference demand. “One of the big surprises last year was the success of open models. They really took off to the point where one out of every four tokens generated today are open models,” Huang said.

Open-weight models reduce friction across the entire deployment stack and make experimentation cheaper. They also shorten iteration cycles and allow organizations outside the hyperscalers to deploy inference at a meaningful scale. That does not just diversify who is running AI models but also materially changes how often inference runs and where it runs.

From Nvidia’s perspective, it matters not whether a model is proprietary or open, but how much inference activity it creates. Open models tend to proliferate across a much wider range of environments, from enterprise clusters to regional cloud providers and on-premises deployments.

Each deployment may be smaller, but the aggregate effect is an expansion in total token volume. More endpoints generating tokens more often drives sustained demand for compute, networking, and memory, even if average margins per deployment are lower. “That has driven the demand for Nvidia and the public cloud tremendously, which explains why right now Hopper pricing is actually going up in the cloud.”

Open models often run outside the largest hyperscale environments, but they still require efficient, reliable hardware. By focusing on system-level efficiency and uptime, Nvidia is positioning itself to serve a broader range of inference scenarios without the need for separate product lines.

Ultimately, Huang’s comments suggest that Nvidia views open models as complementary to its business. They expand the market rather than cannibalize it, provided the underlying infrastructure can support them efficiently. “All told, the demand that’s being generated all over the world is really quite significant.”

Across discussions of Rubin, power delivery, inference economics, open models, and geopolitics, Huang’s comments painted a consistent picture: Nvidia is optimizing for systems that stay productive, tolerate failure, and operate efficiently under real-world constraints. Peak performance still matters — it always will — but it no longer appears to be the sole driving factor.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.

- Jeffrey KampmanSenior Analyst, Graphics

- Paul AlcornEditor-in-Chief