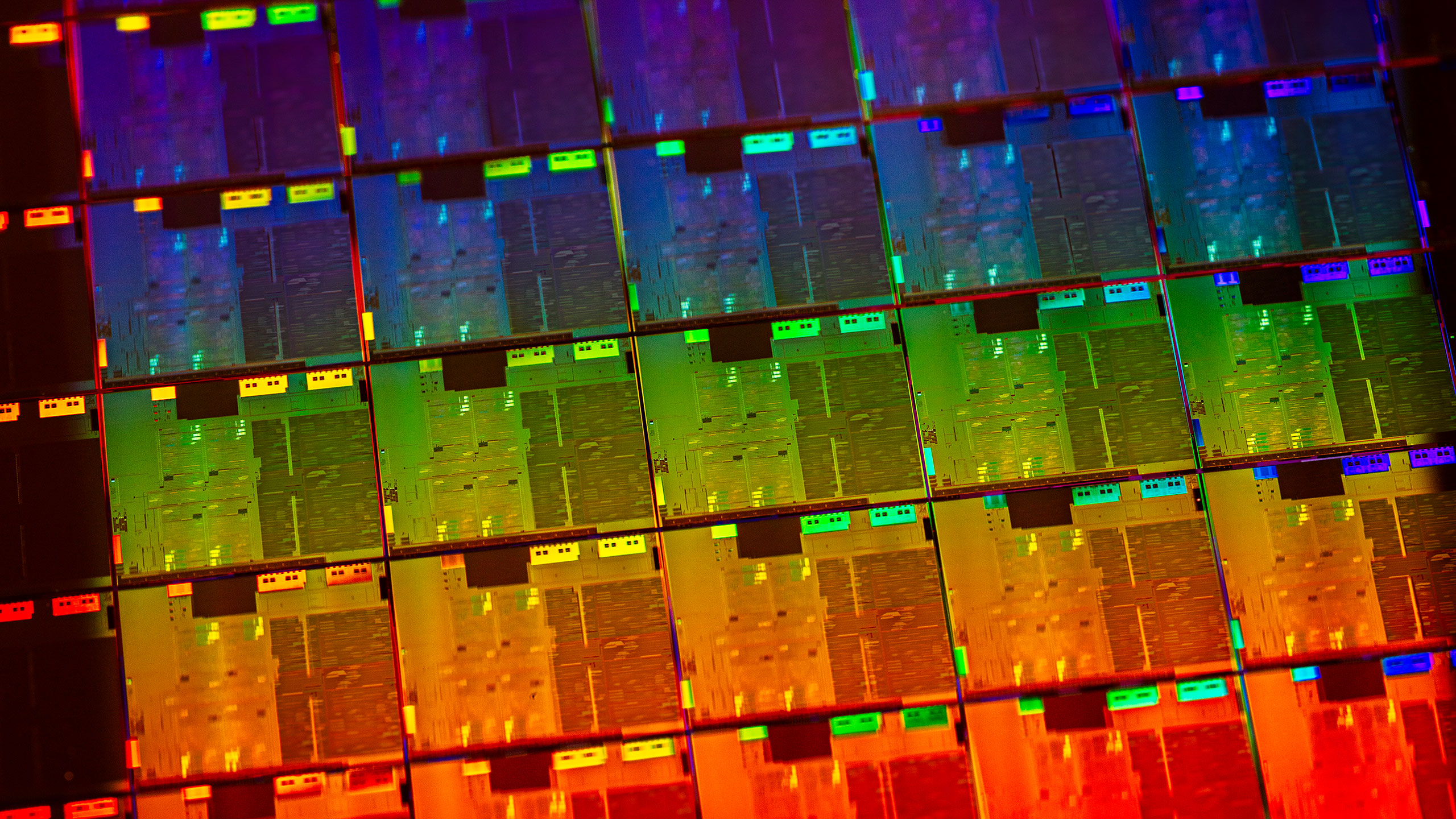

A deeper look at the tightened chipmaking supply chain, and where it may be headed in 2026 — "nobody's scaling up,” says analyst as industry remains conservative on capacity

We sit down with two high-profile analysts to get some answers about where the chipmaking industry might be headed next.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

From memory shortages to rising GPU prices, 2025 seemed like a year of significant scarcity in the supply chain for all things semiconductors. But what does the future hold for this super-tight market in the years to come?

One school of thought suggests that in a couple of years, the story goes, today’s hyperscaler accelerators will spill out into the secondary market in a crypto-style deluge. Cheap ex-A100s and B200s – which could be considered AI factory cast-offs –will suddenly become available for everyone else looking to buy.

Data center hardware is often assumed to have a finite and sometimes short lifecycle, with depreciation schedules and refresh cycles that push older hardware into uselessness after a few years. But another group suggests AI compute doesn’t behave like a consumer GPU market, and the ‘three years and it’s done’ assumption is shakier than many people want to admit. As Stacy Rasgon, managing director and senior analyst at Bernstein, said in an interview with Tom’s Hardware Premium, the idea that “they disintegrate after three years, and they're no good, is bullshit.”

Some believe the present tightness in the market isn’t just a temporary crunch but is more a structural condition of the new post-AI norm in the market, with a closed loop where state-of-the-art hardware circulates between a handful of cloud and AI giants.

So what’s the reality? Ben Bajarin, an analyst at Creative Strategies, describes the current moment as a “gigacycle” rather than another chip boom. In his modelling, global semiconductor revenues climb from roughly $650 billion in 2024 to more than $1 trillion by the end of the decade. “There’s some catch-up necessary, but there’s also the fact that the semiconductor industry remains relatively conservative, because they are typically cyclical,” Bajarin said in an interview with Tom’s Hardware Premium. “So everybody’s very concerned about overcapacity.”

That conservatism matters because chipmaking capacity takes time, effort, and a lot of money to stand up and bring online. It’s for that reason that we’re likely to see tightness in the market remaining for a little while yet: demand is spiking, yes, but companies aren’t that keen to stand up their supply until they can absolutely guarantee a return. “They don’t want to be stuck with foundry capacity or supply capacity that they can’t use seven or eight years from now,” Bajarin said.

Looking at the numbers

According to Bajarin’s analysis, AI chips represented less than 0.2% of wafer starts in 2024, yet already generated roughly 20% of semiconductor revenue – a huge concentration on a single space, which helps explain why the shortages feel different from the pandemic-era GPU crunch. In 2020 and 2021, consumer demand surged, and supply chains seized up, but the underlying products were still relatively mass market in manufacturing terms. But today’s AI accelerators require leading-edge logic, exotic memory stacks, and advanced packaging.

It’s possible to make more of them, but not quickly, and not without knock-on effects. “If you look at the forecasts for wafer capacity or substrate capacity, nobody's scaling up,” cautions Bajarin.

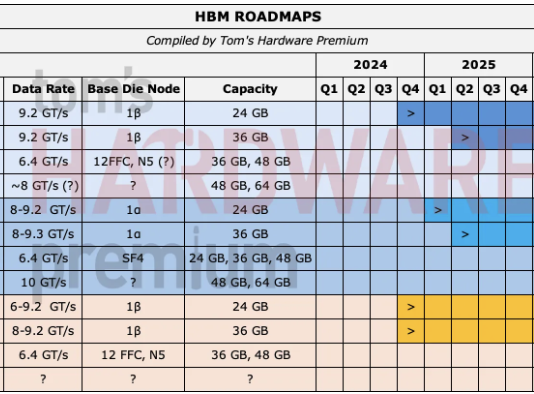

Rasgon told us that while not everything is tight, the “really tight” parts of the system are concentrated in memory. Rasgon pointed to Micron, one of the three global DRAM giants, which has said memory tightness could persist beyond 2026, driven in large part by AI demand and High Bandwidth Memory (HBM). It’s notable that Micron recently closed down its consumer-facing business, Crucial, to focus on the more lucrative products it can sell – and markets it can sell into.

HBM is a different manufacturing and packaging challenge that can hoover up production capacity. HBM production consumes far more wafer resources than standard DRAM, according to Rasgon – so much so that producing a gigabyte of HBM can take “three or four times as many wafers” as producing a gigabyte of DDR5, which means shifting capacity into HBM effectively reduces the total number of DRAM bits the industry can supply.

Memory makers prioritising HBM for accelerators doesn’t just affect hyperscalers. It has a knock-on effect on PCs, servers, and other devices when standard DRAM is tighter and pricier than it would otherwise be, which is why companies have been pushing up prices for consumer hardware in recent weeks and months. Hyperscalers can often swallow higher component costs because they monetise the compute directly, whether through internal workloads or rented-out inference. Everyone else tends to feel the squeeze more immediately: OEMs and system builders face higher bill-of-materials costs and retail pricing changes for the worse if you’re an end customer.

Bajarin believes HBM will be one of the defining constraints of the remainder of the decade, projecting it to grow fourfold to more than $100 billion by 2030, while noting that HBM3E can require about three times the wafer supply per gigabyte compared with DDR5. But he’s not alone in thinking that: Micron has even talked about being unable to meet all demand from key customers, suggesting it can supply only around half to two-thirds of expected demand, even while raising capex and considering new projects.

Where’s the bottleneck?

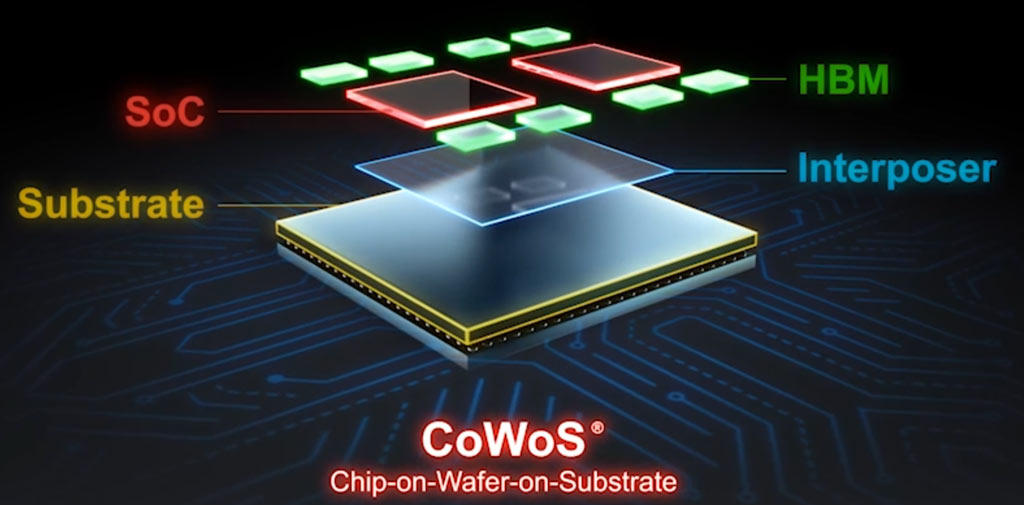

There are a number of reasons for the current tightness, but even if the market had infinite wafers and infinite memory, it could still run into a chokepoint: advanced packaging.

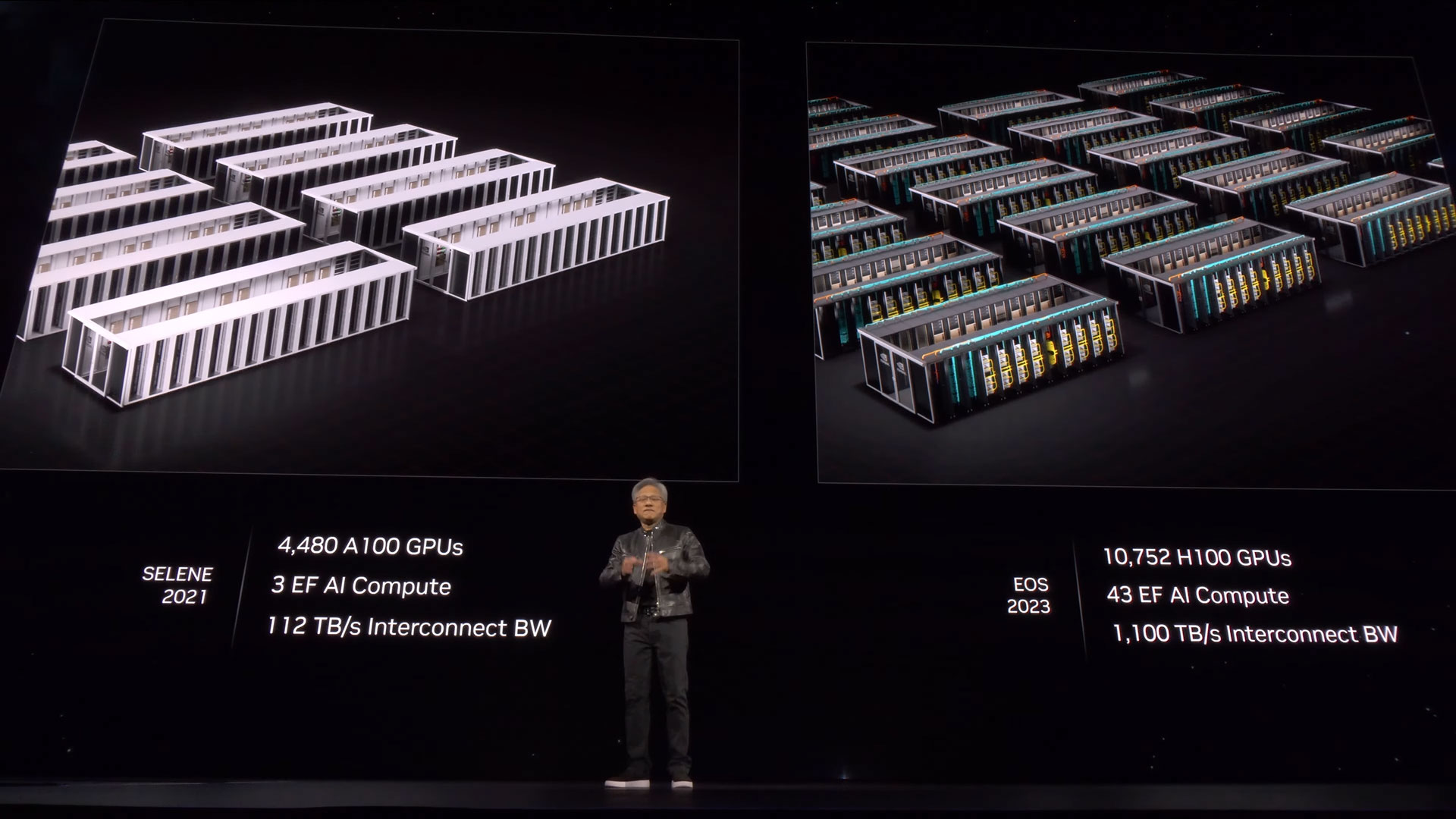

The industry has been ramping up its CoWoS (chip-on-wafer-on-substrate) capacity aggressively, but it has also been unusually open about how hard it is to get ahead of demand. In early 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang said overall advanced packaging capacity had quadrupled in under two years but was still a bottleneck for the firm.

It’s not just Nvidia that is reckoning with the challenge. TrendForce, which tracks the space closely, has projected TSMC’s CoWoS capacity rising to around 75,000 wafers per month in 2025 and reaching roughly 120,000 to 130,000 wafers per month by the end of 2026. Such growth is a big leap – but it’s also unlikely to loosen current capacity constraints.

Bajarin highlighted the reason why in his analysis: CapEx by the top four cloud providers — Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Meta — doubled to roughly $600 billion annually in just two years. Rasgon noted that some companies can wind up supply-constrained for reasons that have nothing to do with leading-edge demand being “off the charts.” In Intel’s case, he argued, it’s partly about where demand is versus where capacity has been cut. “They were actually scrapping tools in that older generation and selling them off for pennies on the dollar,” he said.

‘Forecasts’ versus ‘guesses’

Although it may seem obvious that demand will continue to grow because of the way the big tech companies are splashing the cash, it can be difficult to accurately forecast future demand because of the way the chip market works.

Rasgon said semiconductor companies sit “at the back of the supply chain,” which limits their ability to see end demand clearly, and encourages behaviour that makes the signal noisier. It’s a vicious circle exacerbated when supply is particularly tight and lead times stretch because customers start hoarding the chips they have and double-ordering new options, because they’re trying to secure parts from anywhere they can.

That can make demand look artificially huge until lead times ease and cancellations begin. Suppliers want to avoid being caught by sizing their production for a demand that doesn’t materialize. “Forecasting in semiconductors in general is an unsolved problem,” Rasgon said. “My general belief is that most, or frankly all, semiconductor management’s actual visibility of what is going on with demand is precisely zero.”

Bajarin points out that the industry works “very methodically” because it remembers boom-bust cycles, especially in memory. “We’re just going to have to live in a foreseeable cycle of supply tightness because of these dynamics that are historically true of the semiconductor industry,” he said.

When the market unwinds itself, and supply normalizes is, as is befitting a market that struggles with forecasting, impossible to tell. “As long as we're in this cycle where we're really building out a fundamental new infrastructure around AI, it's going to remain supply-constrained for the foreseeable future, if not through this entire cycle, just because of prior boom-bust cycles within the semiconductor industry,” said Bajarin.

But even if the industry could magically print accelerators, it still needs somewhere to run them. Data centers take time to build, to connect to power, and to cool at scale. “Even if we make all these GPUs, we can’t really house them because we don’t have the gigawatts,” said Bajarin. However, with the planning of small modular reactors and the expansion of electricity grids, there’s hope that the need can be met – eventually.

Chip cycles and recycling

Another potential unblocker of the tight market is the opportunity to reuse older generation GPUs as they enter the traded market, thanks to newer generations of chips constantly being cycled through big tech companies who want the cutting edge for inference and training.

Already, you can find small volumes of older data center GPUs on the market, including listings for Nvidia A100-class hardware through resellers and brokers. But the odd older generation of chips existing is a world away from a crypto-style glut of former AI accelerators appearing on the market. While AI firms want all the cutting-edge chips they can get their hands on, they’re not necessarily disposing of their older stock, either. A top-end accelerator isn’t a consumer graphics card that becomes obsolete in a couple of years. It’s capital equipment. And AI companies are learning to sweat it.

OpenAI CFO Sarah Friar underlined this in November, admitting that OpenAI still uses Nvidia’s Ampere chips – released in 2020 – for inference on its consumer-facing models. Training might use bleeding-edge tech, but inference can profitably run on older generations for a long time. If OpenAI is thinking that way, so too will other companies in the space. “Absolutely, the older stuff is still being used,” says Rasgon. “And in fact, not only is it being used, it's being used very, very profitably.”

For now, the clearest takeaway is that the current tightness isn’t only about making more chips. It’s about whether the industry can build enough of everything around them – including the buildings, cooling, and grid connections to run them – fast enough to match demand that’s still accelerating. “We're going to remain in a relative supply constraint across all of these vectors until either we've built the entire thing out and we have enough compute,” Bajarin said, “or it's a bubble, and it crashes.”

Chris Stokel-Walker is a Tom's Hardware contributor who focuses on the tech sector and its impact on our daily lives—online and offline. He is the author of How AI Ate the World, published in 2024, as well as TikTok Boom, YouTubers, and The History of the Internet in Byte-Sized Chunks.