Chip scarcity assaults auto industry amid the worsening Nexperia and DRAM crisis — fragile sector rocked by undersupply, which may end worse than the 2021 shortage

Automakers let their safety stocks dwindle just as chipmakers shifted focus to AI.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to buy a new car in the coming year? Act quickly – or be prepared to pay over the odds, or wait a little longer than you might ordinarily have done so. The auto industry is currently facing a massive supply crunch in vital chips, resulting in car manufacturer Honda entering the new year shutting down its production facilities in Japan and China because it can’t get enough chips to power their vehicles.

The carmaker’s challenges come from the ongoing argument over control of Nexperia, the Chinese-Dutch chip supplier whose ownership is under debate and subject to repeated sanctions. For months, Japan's Automobile Manufacturers Association has warned its members that the chip supplier couldn’t guarantee a steady stream of chips to meet the demand needed for new vehicles.

The pressure isn’t coming from one single missing component. It’s a combination of a geopolitical shock hitting the supply of low-margin, high-volume parts for vehicles, and a market-wide shock in memory chips, driven by the popularity of AI data centers, that is hitting software-heavy, screen-filled cars first. Modern vehicles contain thousands of semiconductors, and assembly lines can’t wait for one low-cost component that is missing.

DRAM and industry qualification

But it’s not the challenges facing Nexperia that have impacted auto manufacturers: the ongoing memory crisis, which is negatively affecting the production of DRAM chips, has vehicle makers scrabbling to secure supply and looks likely to push up prices in the next 12 months.

The memory crunch is its own beast, hitting cars in a specific way. Automotive-grade components are expected to last a decade or more and keep working in all conditions, whether that’s the cold of deep winter or the under-bonnet heat. Industry qualification regimes like AEC-Q100 demand broad temperature grades and strong reliability tests. That pushes up the cost and narrows the pool of usable suppliers, especially in EVs, where thermal management, vibration, and power efficiency are already tight constraints.

“The developing supply issue may remind some of the chip supply shock that the global auto industry went through in 2021,” cautioned Dan Levy, senior equity analyst at Barclays, in a recent research note. The concern about history repeating itself has driven many within the auto industry to try and snap up a reliable chip supply, exacerbating the already tight situation, said Levy.

Data from S&P Global Mobility suggests that the demand for those chips within the auto sector will push up the cost that OEMs and their auto suppliers are willing to pay by between 30 to 100% in 2026 and 2027. Separate research by Bernstein suggests that the automotive semiconductor industry was worth around $77.8 billion in 2024, growing 15% in a compound annual growth rate since 2019. The same analysis highlights a dangerous disconnect in the supply chain: while semiconductor manufacturers are currently sitting on bloated inventories of over 160 days – nearly 50% higher than pre-pandemic levels – automakers have let their own safety stocks dwindle. OEM inventory days have dropped steadily throughout 2024 to just 59 days, leaving them with virtually no buffer to absorb the shock of the specific memory shortages predicted.

Dwindling supply

The price increase results in an end cost not significantly more than other industries are currently paying for the same DRAM chips – the auto sector has long benefitted from lower prices compared to other industries, but still is a significant increase for a sector not used to paying top dollar. “The cliff that we have right now is not a case of us running out of chips, but it's about actually the conversion points,” said Akshay Baliga, director at AlixPartners, in an interview with Tom’s Hardware Premium. “It’s not that we can no longer make semiconductors, or we can’t make enough semiconductors. We’re in a situation where the industry is constrained by qualification and requalification,” he added.

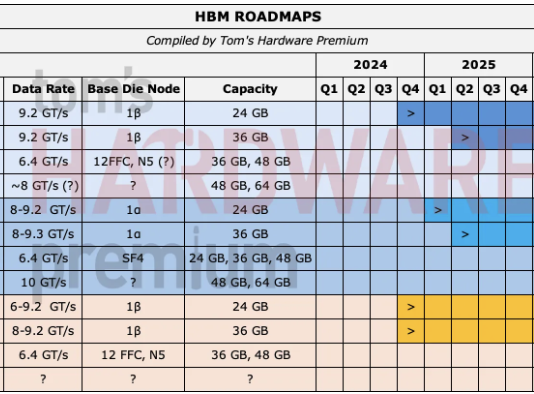

The problem is that chipmakers aren’t exactly enticed to produce more for the auto industry by default: while the likes of Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron supply around 88% of the automotive industry’s need for DRAM, according to Barclays data, they only account for around 5% of the chipmakers’ total revenue. Because the auto industry isn’t a massive market for those chipmakers, and because they’re comparatively poorly compensated for their chips when looking at other industries, notably the AI sector, the manufacturers are starting to put what production capacity they do have into making High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) chips. That “will to some extent constrain the production of auto chips,” Levy said.

But what impact that will have on automakers is less certain. “The impact of structural memory shortages on automakers and Tier 1 suppliers will primarily depend on their respective inventory levels and capacity binding agreements,” said TrendForce analyst Caroline Chen in an interview with Tom’s Hardware Premium. “Despite short-term pressures from price hikes and extended lead times, the correlation between individual components and vehicle price increases remains weak.”

Competition from HBM could last through 2027

Memory makers have spent the last two years pivoting capacity toward high-bandwidth memory (HBM), which feeds Nvidia-class accelerators, because that’s where the margins are. Reuters reports the resulting squeeze is spreading across multiple memory types, with inventories tightening and prices in some segments surging. Analysts warn the shortfall could persist into late 2027. When capacity, packaging lines, and engineering talent are being pulled toward the AI boom, legacy memory products, including those used in vehicles, risk becoming the thing suppliers would rather not make unless they’re paid properly.

Although the entire sector is under pressure, the financial and operational burden isn’t distributed evenly: Tesla and Rivian are considered the most exposed manufacturers due to their advanced zonal architectures and high reliance on complex ADAS systems, which need DRAM in abundance. Tesla's vehicles, for instance, carry roughly five times the DRAM content of lower-content legacy models. And geographically, the risk is most concentrated in China, where vehicles carry approximately 50% more DRAM content than those produced for the North American or European markets due to the high penetration of advanced cockpit features.

BOM costs will inevitably be affected

Analysts reckon the DRAM cost of an average US vehicle could rise from $50 to $100, which represents only around 0.2% of the total bill of materials. “Although EV demand for DRAM/NAND is surging, memory still accounts for a limited percentage of total vehicle costs,” explained Chen. But the harm begins to become obvious for premium electric vehicles where DRAM content already exceeds $200. There, costs could balloon to $400 per vehicle, accounting for up to 1% of the total manufacturing cost for a mid-level EV like the Tesla Model 3 or Y.

To mitigate these rising costs and potential supply gaps, some manufacturers may be forced into what analysts say is “de-contenting” their vehicles by scaling back on high-tech offerings. This could include reducing the capability of ADAS systems, which use 5.5 times more DRAM than standard Level 2 systems, or removing generative AI features, which require double the standard DRAM density. Other options for conserving supply include offering fewer or smaller displays within the cabin.

The loss of those features is where the harm differs from the upcoming 2026 supply shortage and the one that racked the industry during the COVID-19 pandemic six years ago. The 2021 crisis impacted basic chips used in almost every electronic control unit across a car, while this shortage is concentrated in advanced compute functions like the cockpit and central processing. So while the shortage might prevent an automaker from offering a premium infotainment system or advanced self-driving features, it’s far less likely to stop the assembly line for basic vehicle production. But the effect is still significant, and manufacturers seem likely to respond. The auto industry will eventually need to redesign its systems to move away from older DRAM technologies that are set to be phased out after 2027, reckons Barclays’ Levy.

A shifting market

Another alternative to try and tackle the changing market dynamics is to centralise compute in ways that reduce total DRAM demand. “What we've seen increasingly with clients is they're trying to get an understanding of where the choke points are,” said Baliga. But changing vehicle designs can’t be done overnight, and doesn’t remove the underlying challenge.

Automakers can fix their own issues, but they can’t account for the changes made by other industries – and while they might be willing to take the hit on the small margin of the overall vehicle cost, they probably can’t account for the change in cost from import tariffs. “Given the numerous variables affecting final pricing, it is difficult to directly link the cost volatility of a single component to adjustments in market retail prices,” said Chen.

As long as AI infrastructure keeps hoovering up high-margin capacity, and chip supply remains a geopolitical lever, automotive manufacturers will be trying to negotiate with two parties that don’t particularly care about the price sensitivity of the auto market. The safest assumption for the next year or two is simple: the electronics content in cars will get more expensive – and buyers, one way or another, pick up the bill.

Chris Stokel-Walker is a Tom's Hardware contributor who focuses on the tech sector and its impact on our daily lives—online and offline. He is the author of How AI Ate the World, published in 2024, as well as TikTok Boom, YouTubers, and The History of the Internet in Byte-Sized Chunks.