Photonics and high-speed data movement is the next big AI bottleneck — following copper, power, DRAM, and NAND

Voracious demand from the generative AI revolution has already chewed up power grids, copper supplies, and data centers

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

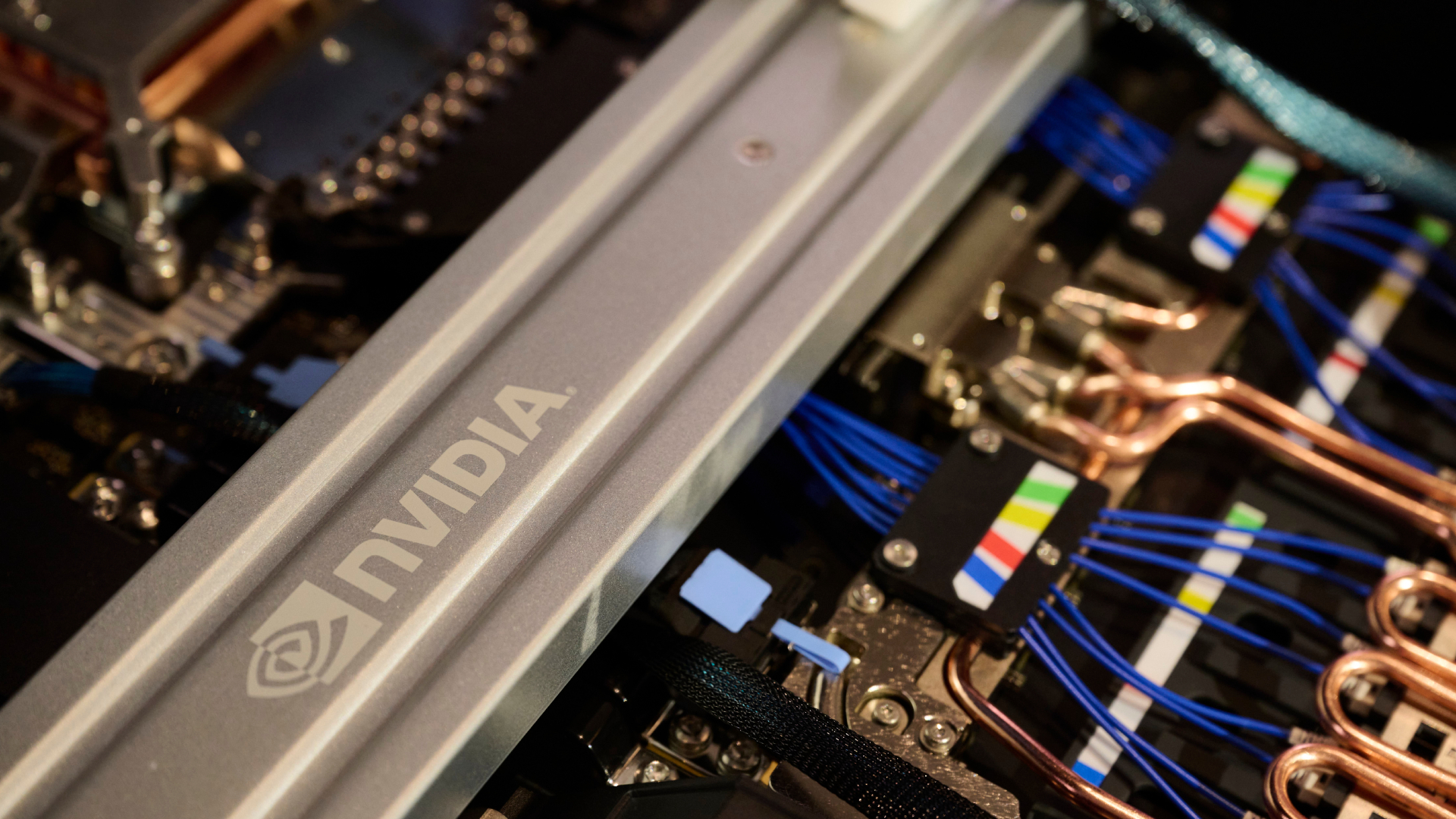

The voracious appetite of the generative AI revolution has overhauled any number of industries so far in its three-year history. First, it upended demand for high-end chips, pushing companies like Nvidia to record high valuations and putting pressure on all parts of the manufacturing process to churn out chips to meet that need. Then it began to make power grids break and buckle, requiring the need for a rethink about how we send energy to data centers. And those data centers are also facing the strain as they’re needed more often for AI training and inference, even eking out extra demand for commodities like copper that are integral to their operations.

Those data centers need to respond to that demand for more capacity and the challenges of copper shortages, argues Vaysh Kewada, CEO and co-founder at Salience Labs, a silicon-photonics company focused on networking bottlenecks in AI data centers. The bigger and more intensive AI models that continue to roll out, alongside the shift away from chatbots to agentic AI, are pushing those within the sector towards photonics.

“We're targeting the scale up domain of AI data centers, where we're seeing that they're increasingly limited by not just the bandwidth, but the latency of predictability, especially as we scale to larger workloads and agentic workloads,” she said in an interview with Tom’s Hardware Premium. For that reason, “there’s a lot of attention at the moment around photonics.”

Others agree: 2026 is “the year of increasing visibility into design wins and building momentum for silicon photonics,” wrote Aaron Rakers, equity analyst at Wells Fargo Securities, in a recent research note. Wells Fargo estimates that the total addressable market for photonics could end up being $10-12 billion by 2030, thanks to the industry’s shift to bigger capacity.

That sounds like good news, but it comes with a catch. Behind the bullish forecasts, those within the photonics industry warn that, like all those sectors that have been eaten up and spat out before, the next set of constraints, including reliability, packaging, manufacturing capacity, and how data is actually routed once it hits fibre, could become the next hard limit on AI scaling.

Data is the new choke point

The boom in photonics might come as a surprise to some. “Photonics is something that already exists within the data centre today,” said Vivek Raghunathan, CEO and co-founder at Xscape Photonics, in an interview with Tom’s Hardware Premium. “Optical cables and the silicon photonics technology already exist when it comes to connecting different switches as part of a pluggable transfer ecosystem.”

But now that section of optics is being pushed out of there and into ultra-fast links that link large numbers of GPUs into a single compute fabric. “Ultimately, the network is the bottleneck for these workloads, because they're just far too large to run on a single GPU,” Kewada said.

Using photonics means you can get between 10 and 100 times more information back and forth from the memory before they output a single stream of reference, Raghunathan explained. That’s important because what AI systems do now is changing, requiring that extra information shifting. The average AI user is moving from asking single prompts of a model to running chains of tasks, and Kewada said that the hardware is already struggling under current AI use. “If it’s a problem now, it becomes an even bigger problem when it comes to agentic workloads, and that's heavily latency- and balance-sensitive,” she explained.

Photonics also matters because “fundamentally, the current copper-based interconnects just cannot meet that bandwidth requirement,” explained Raghunathan. He warns that “the current approach is going to break down sooner than later.” The solution is the photonics approach, where you can “squeeze a lot of bandwidth in a single strand of fiber, which is extremely small,” Raghunathan added. Kewada points out that dedicated AI data centers want to move from 200‑gigabit‑per‑second (Gb/s) links to 400 Gb/s links as AI clusters behave less like traditional IT and more like large distributed machines.

The photonics push inside AI data centres is increasingly being shaped by TSMC. Its COUPE (Compact Universal Photonic Engine) platform has become a key reference point for integrating photonic and electronic circuits on a wafer, following rumors, years beforehand, with an eventual unveiling at SEMICON in Taiwan in September 2025, and first mocked up in December. Other companies, including Marvell, Broadcom, and Nvidia, are all also engaged in the sector, with Nvidia helping define the performance requirements that become standards by default.

But Nvidia isn’t the only voice in the space. Broadcom has been leading the debate on co-packaged optics (CPO), betting that moving optics closer to silicon is the only realistic way to get past copper’s limits when scaled up. Marvell has also pushed photonics-heavy designs in bigger AI clusters, as well as spending cash on investments, including buying photonics startup Celestial AI for up to $5.5 billion.

Tackling the routing problem

Most of the focus has recently been on solving the problems of getting optics away from chip switches and onto fiber. But once the data is there, it still has to be routed around a cluster. “All billions of dollars has been spent onto the I/O, but less has been thought about of what you do once the data is there,” Kewada said.

Salience Labs is betting on optical circuit switching. “Rather than it being an OEO [optical-electrical-optical] switch, it's a purely optical switch; we're never transforming that data into the electronic domain,” Kewada explained. That matters because every optical-to-electrical-to-optical hop costs power and, crucially for AI, adds delay. The company is seeing huge interest from those trying to scale up to meet the current needs of AI.

But there’s a broader problem within the photonics sector. “I would say that it is mentally ready for it, but practically not ready for it,” Raghunathan explained.

Part of the issue is in capacity. Many photonics components rely on III-V semiconductors (compound semiconductors made from the associated groups in the periodic table), which aren’t produced in the same numbers as mainstream silicon. Raw materials supply is also tight, said Kewada. And that’s before you get to packaging. “This requires sub-micron alignment,” Raghunathan said. “They are typically glued onto that die. So now the industry has started thinking about, how do I make that interface detachable?” It’s one of many questions the industry is being asked — and asking itself — to address the challenges ahead.

The push towards photonics feels inevitable, but just because it’s inevitable, it doesn’t mean the sector is ready. Manufacturing scale, raw materials, packaging, and reliability are still unanswered issues. And if the industry doesn’t get ahead of those constraints, it risks replaying the same shortages it has already lived through with chips, copper, and power — but this time the choke point could be the network itself. “The volume here is going to be two orders of magnitude higher than what the industry has seen so far,” said Raghunathan. “The entire optics industry has never seen such a volume ever before.”

It's something on the mind of Kewada, too. “We’re in for some interesting times if we see the attention on photonics continue to grow, and especially for next-generation bandwidth,” she said, “if people look towards larger-scale deployment.”

Chris Stokel-Walker is a Tom's Hardware contributor who focuses on the tech sector and its impact on our daily lives—online and offline. He is the author of How AI Ate the World, published in 2024, as well as TikTok Boom, YouTubers, and The History of the Internet in Byte-Sized Chunks.