Nvidia's focus on rack-scale AI systems is a portent for the year to come — Rubin points the way forward for company, as data center business booms

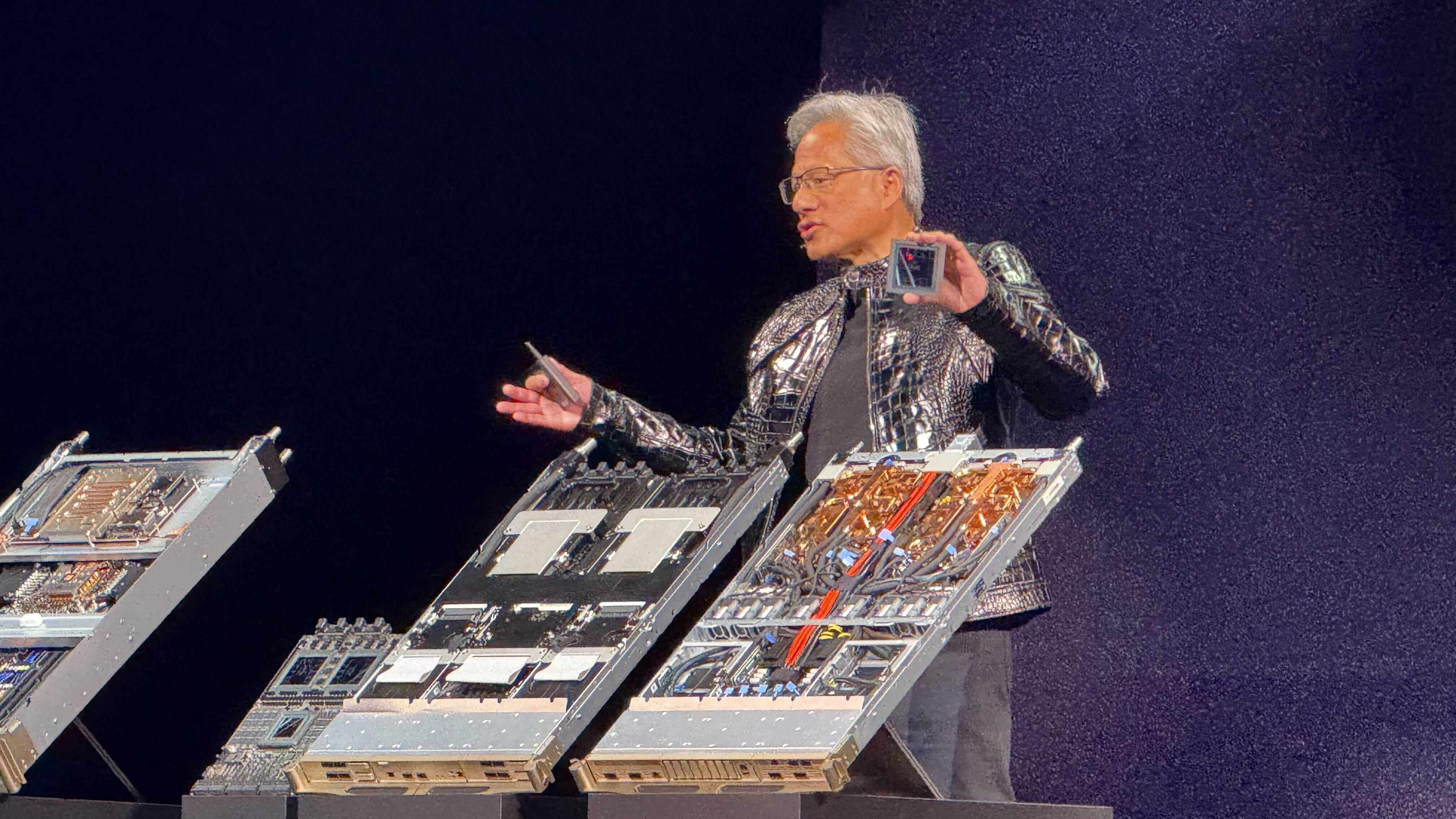

Nvidia took to the stage at CES 2026 to show off its latest rack-scale solutions.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Those who tuned into Nvidia’s CES keynote on January 5 may have found themselves waiting for a familiar moment that never arrived. There was no GeForce reveal and no tease of the next RTX generation. For the first time in roughly five years, Nvidia stood on the CES stage without a new GPU announcement to anchor the show.

That absence was no accident. Rather than refresh its graphics lineup, Nvidia used CES 2026 to talk about the Vera Rubin platform and launch its flagship NVL72 AI supercomputer, both slated for production in the second half of 2026 — a reframing of what Nvidia now considers its core product. The company is no longer content to sell accelerators one card at a time; it is selling entire AI systems instead.

From GPUs to AI factories

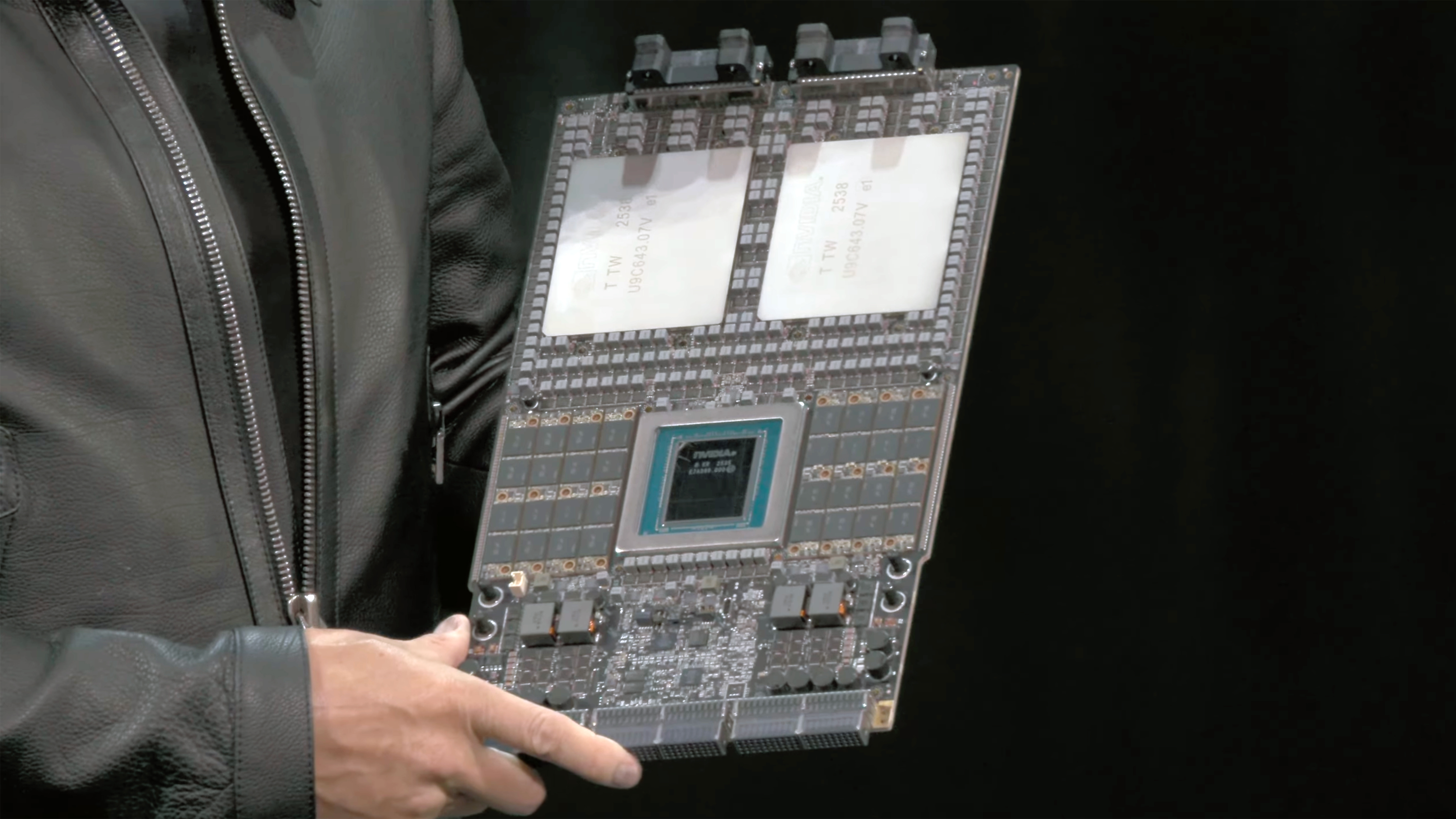

Vera Rubin is not being positioned as a conventional GPU generation, even though it includes a new GPU architecture. Nvidia describes it as a rack-scale computing platform built from multiple classes of silicon that are designed, validated, and deployed together. At its center are Rubin GPUs and Vera CPUs, joined by NVLink 6 interconnects, BlueField 4 DPUs, and Spectrum 6 Ethernet switches.

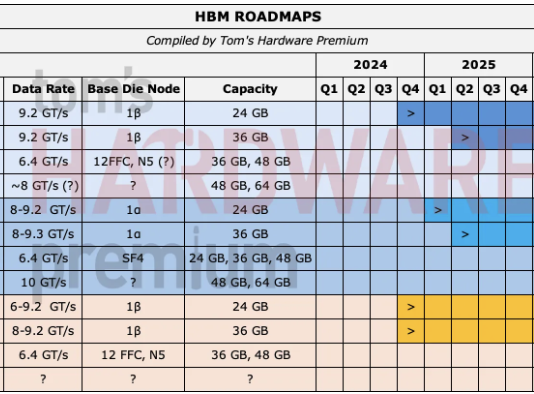

Each rack integrates 72 Rubin GPUs and 36 Vera CPUs into a single logical system. Nvidia says each Rubin GPU can deliver up to 50 PFLOPS of NVFP4 compute for AI inference using low-precision formats, roughly five times the throughput of its Blackwell predecessor in similar inference workloads. Memory capacity and bandwidth scale accordingly, with HBM4 pushing hundreds of gigabytes per GPU and aggregate rack bandwidth measured in the hundreds of terabytes per second.

These monolithic Vera Rubin systems are designed to reduce the cost of inference by an order of magnitude compared with Blackwell-based deployments. That claim rests on several pillars: higher utilization through tighter coupling, reduced communication overhead via NVLink 6, and architectural changes that target the realities of large language models rather than traditional HPC workloads.

One of those changes is how Nvidia handles model context. BlueField 4 DPUs introduce a shared memory tier for long-context inference, storing key-value data outside the GPU frame buffer and making it accessible across the rack. As models push toward million-token context windows, memory access and synchronization increasingly dominate runtime. Nvidia is seems to be taking the view that treating context as a first-class system resource, rather than a per-GPU issue, will unlock more consistent scaling.

This emphasis on pre-integrated systems reflects how Nvidia’s largest customers now buy hardware. Hyperscalers and AI labs deploy accelerators in standardized blocks, often measured in racks or data halls rather than individual cards. By delivering those blocks as finished products, Nvidia shortens deployment timelines and reduces the tuning work customers must do themselves. CES became the venue to outline that vision, even if it meant leaving traditional GPU announcements off the agenda.

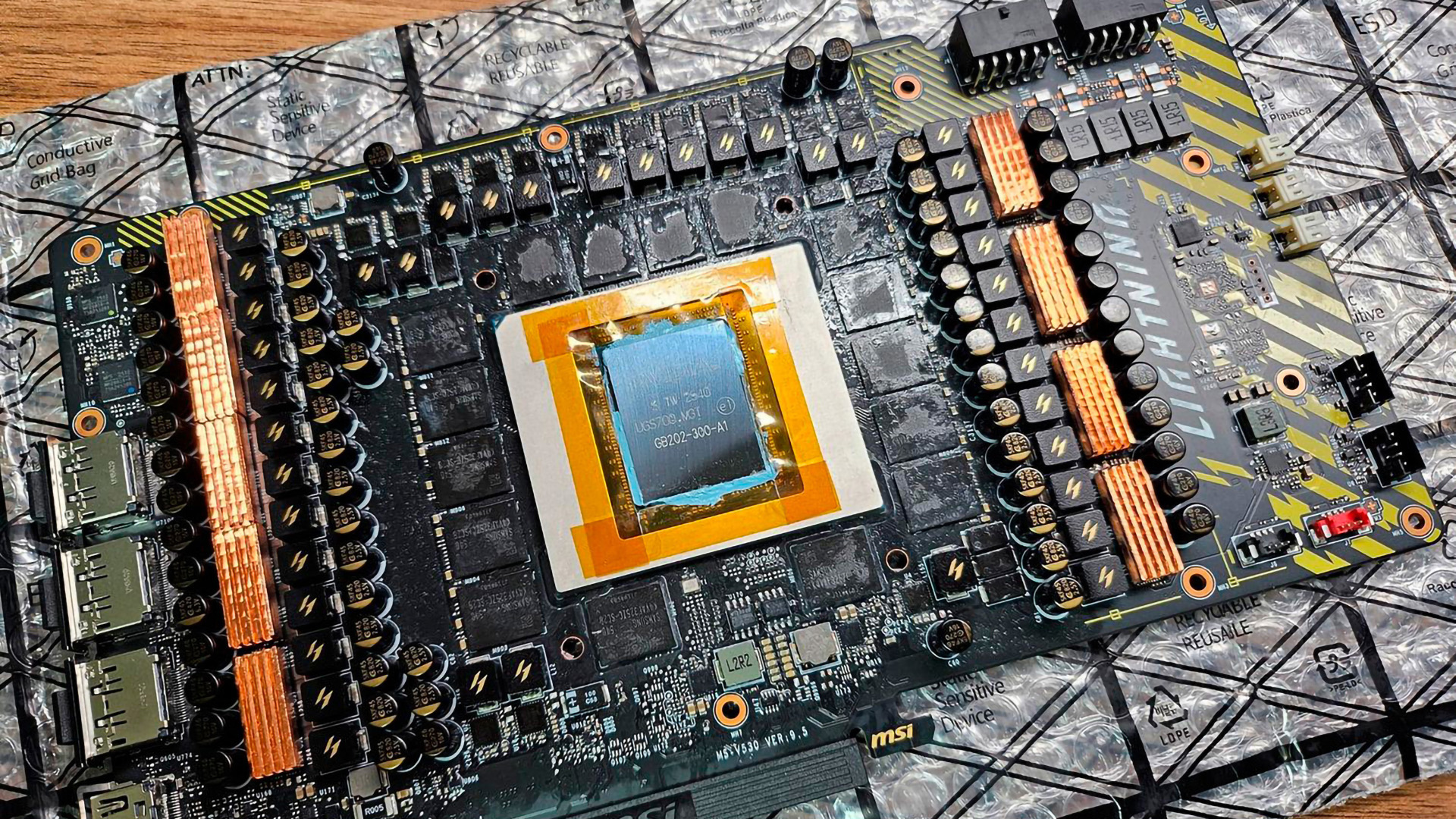

No New GeForce cards

Suddenly, the lack of a new GeForce announcement becomes a whole lot easier to explain. Nvidia’s current consumer line-up of 50-series GPUs is still pretty fresh, and it continues to command prices in excess of $3,500 per unit. Introducing an interim refresh would carry higher costs at a time when memory pricing is at all-time highs, and supply remains tight. The company has also leaned more heavily on software updates, particularly DLSS and other AI-assisted rendering techniques, to extend the useful life of existing GPUs.

From a purely commercial perspective, consumer GPUs now represent a smaller (and, unfortunately, shrinking) share of Nvidia’s revenue and focus than they did even two years ago, let alone five. Data center products tied to AI training and inference account for the majority of growth, and those customers need system-level gains, not incremental improvements in graphics performance.

Lisa Su, during her AMD keynote, said it best: “There's never been a technology like AI.” CES, once a showcase for new PC hardware, has become a stage for AI announcements. This does not mean Nvidia — or AMD for that matter — is abandoning gaming or professional graphics. Rather, it suggests a lengthening cadence between major GPU architectures. When the next GeForce generation arrives, it is likely to incorporate lessons from Rubin, particularly around memory hierarchy and interconnect efficiency, rather than simply increasing shader counts.

Faith in CUDA

Nvidia’s system-centric approach inevitably invites comparison with rivals pursuing similar strategies. AMD is pairing its Instinct accelerators with EPYC CPUs in tightly coupled server designs, while Intel is attempting to unify CPUs, GPUs, and accelerators under a common programming model. Apple has taken vertical integration even further in consumer devices, designing CPUs, GPUs, and neural engines as a single system on a chip.

What distinguishes Nvidia is the depth of its software stack. CUDA, TensorRT, and the company’s AI frameworks remain deeply entrenched in research and production environments. By extending that stack everywhere it can, Nvidia increases the switching cost for customers who might otherwise consider alternative silicon. There are risks to this approach, and large customers are increasingly exploring in-house accelerators to reduce dependence on a single vendor, and complex rack-scale systems raise the stakes for manufacturing or design issues. Because of this, Nvidia’s ability to deliver Rubin on schedule will matter just as much as the performance metrics presented at CES.

Still, the decision to use CES 2026 to spotlight Vera Rubin rather than a new GPU points to where Nvidia sees its future. Let’s face it: We, and Nvidia, all know that the next phase of computing will be defined less by individual chips and more by how effectively those chips are integrated into scalable systems. Nvidia is therefore aligning itself with where the demand and investment are, even if that means placing less emphasis on the hardware that defined the company for decades.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.