Oculus' Uncompromising Obsession With Hardware

I've written before about the seriousness with which Oculus takes the design and manufacturing of its forthcoming Rift virtual reality hardware, and Oculus reaffirmed as much here in Hollywood at Oculus Connect 2 (the company's annual developer conference) this week by dedicating an hour to talking about some of the nuances, difficulties and accomplishments along the road to the final consumer version.

Because this will be one of the first major VR headsets to ship (early next year), and Oculus intends this to be a premium product, a quick look into the making of it shows how obsessed the company has become in getting it right, all while admitting that in the next few years the size of these headsets will need to get even more compact.

[Please forgive the poor quality of the photos. Oculus has not provided the slides from this presentation, and my angle and the quality of my camera conspired against me. I’ve included them nonetheless because I think the images get across the gist of some of the discussion.]

Obsessive Prototyping

One point that Oculus product design engineer Caitlin Kalinowski, and hardware program management team leader Stephanie Lue, emphasized continually during their talk was the parallel nature of the engineering efforts of the HMD, and how once one piece was prototyped, or even manufactured, some other aspect of the HMD had changed, causing even more changes to that one piece. Although the parallelization helped speed up the HMD build, it clearly created some problems as well.

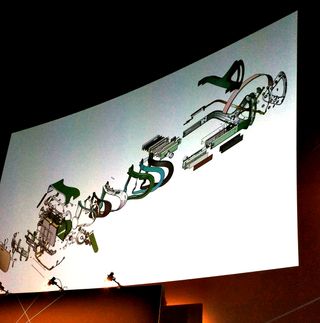

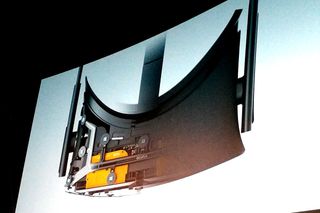

Kalinowski showed an exploded view of the HMD. There are 90 customized mechanical parts, 63 mold-injected parts, and possibly as many as 100 more, not including screws and fasteners – even the Oculus team members didn't know the exact number.

Despite all of the talk about the great hardware, the goal of these painstaking efforts is actually to make the hardware disappear, Kalinowski and Lue said, so that the overall Rift experience, and not the hardware, comes through. To do that required some detailed design and manufacturing efforts around IPD, the fabric, the straps and the audio components.

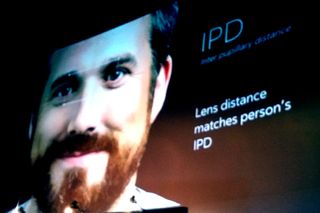

IPD refers to interpupillary distance (the distance between your pupils, in case that's not obvious), and this is different for each person, so the design challenge here was to make something that each user could customize. IPD impacts depth and perception, so this is vital to get right, and at the same time there is an optimal lens distance for the best field of view. Oculus wanted to also ensure that the IPD adjustment mechanism didn't add weight or bulk to the HMD. Great and comfortable immersion requires precision optical control.

Stay on the Cutting Edge

Join the experts who read Tom's Hardware for the inside track on enthusiast PC tech news — and have for over 25 years. We'll send breaking news and in-depth reviews of CPUs, GPUs, AI, maker hardware and more straight to your inbox.

The Crescent Bay prototype (prior to consumer version 1, or CV1) did not have the IPD adjustment. And even CV1 has undergone further IPD refinements between what Oculus allowed users to experience at E3 and the version we've experienced at Oculus Connect. Kalinowski and Lue also revealed that Oculus has collected data on how accurate the IPD adjustments need to be and have allowed for that level of granularity.

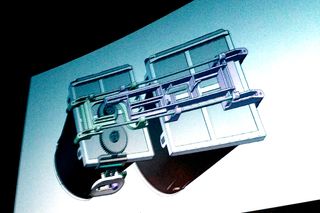

Kalinowski and Lue showed some early prototypes, but Oculus ultimately created a mechanical gear-like design for the adjustment. The IPD team also had to work with optical engineers to mount the lenses to the display, and ultimately all of the IPD adjustment details had to be translated into software and through the SDK.

Fabrics -- Yes, Fabrics

Fabric selection (!) also became a bit of an obsession. If you saw the consumer hardware Rift Oculus plans to ship (see image above), you'll have noticed that it is covered in a silky-smooth fabric. The team searched the U.S., Japan and Austria for material that would stretch but would not block the infrared signals that are essential to constellation tracking (for head tracking). Most fabrics refract light, and they can also trap heat. The fabric Oculus chose, which included some custom fabrics, is permeable.

The next problem involved how the fabric would be manufactured onto the headset. Once the fabric was chosen, it took Oculus an hour to wrap the first one manually, which didn't bode well for a scalable manufacturing process. Ultimately it solved that problem, and later in the talk, Lue said that, broadly speaking, Oculus can manufacture about 100 per hour in a production run.

I've poked a little fun in the past about what Oculus liked to call its "strap architecture," but indeed, the strap is important, because it's really supporting your head, and done right it can actually make the headset feel lighter than it is. Sure enough, there's a demonstrable difference between older versions of the Rift and CV1 (and certainly more so compared with the Gear VR).

Oculus set out to use different fabrics in the strap, as well. The strap includes adjustments on the top and side, which you only have to fit and set once. It also has sensors for LEDs (back of the head tracking) and audio embedded, so it isn't a superfluous piece. Oculus wanted enough force through the strap mechanism to fit your face, reduce weight, and not block the sensors.

Built-In Audio

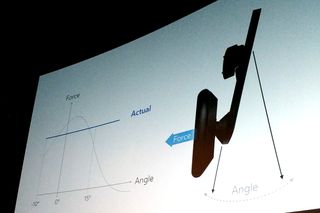

Finally, the CV1 headset includes built in audio headphones. Immersive audio is crucial to the success of any VR experience – a point Oculus demonstrated many times throughout the conference. Once again, the audio must fit any and all heads, and any and all ears, with the proper force (against the ear) for better audio fidelity, and, because Oculus allows you to use your own headphones if you wish, the included headphones need to be somehow removable. For that, Oculus lets you flip the ear pieces up (out of the way) or down. Getting the proper force across all ranges of ear and head shapes was a challenge, and Oculus created a force curve, solving for various variables and coming up with an average force that would work best for everyone.

When asked which parts were the most challenging, Lue cited the assembly of the constellation LEDs on the front plate. The LEDs sit on a flexible PCB, and she said it's a tricky process to get them situated in just the right spot in an automated manufacturing process. Kalinowski noted that the straps were particularly difficult as well, because Oculus is molding hard and soft parts together in the same tool. She said injection molding people generally thought they were crazy to try this, but in the end, the straps, which use a variety of materials, were created without any seams.

There may be further refinements to the hardware between now and the Q1 2016 ship date. For example, although Kalinowski and Lue would not commit to the details or the certainty, they are looking at alternate facial foam material to enhance the comfort for people who wear glasses, which is a continuing point of contention and discussion. They also took some input from attendees.

If this Oculus obsession with the hardware seems a bit overwrought, consider that from iteration to iteration, as the HMD has become lighter and more comfortable, I've found that I'm more comfortable playing games on the Rift longer and longer. Fit, as I've found, has a correlation to function, and at times when I've been strapped in too tightly or too loosely, I've found some discomfort in playing (meaning dizziness). When the HMD is adjusted properly and I dial in the focus to my liking, I honestly do start to forget that the headset is on at all.

Fritz Nelson is the Editor-In-Chief of Tom's Hardware. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Follow Tom's Hardware on Twitter, Facebook and Google+.

-

skit75 Makes sense if you want VR to not fall down the path of 3D.Reply

I remember standing in very "gimicky" corral type stands ~15 years ago to help prevent inevitable falling/disorientating sensations with basically a motorcycle helmet on your head. They were like a carnival side-show and not taken very seriously at all. They were mostly tourist traps.

Hardware evolution has sparked interest from the STEM fields and if done correctly, will catapult VR technology into the next century.

As a gamer, I for one cannot wait until the VR parks become the new "amusement parks". Think of the old Laser Tag buildings and skating rinks being converted into virtual worlds that can be changed on the fly, like a real time D&D game with a game master manipulating environmental effects for the players running around with OR headsets and mock weapons =)

https://thevoid.com/

If it isn't taken seriously right out of the gate, it will continue to make the fad appearances, like 3D. I drool at the thought of playing ARK in a skating rink or football field for that matter, with an OR headset on screaming for my life, running in full sprint from a T-Rex because I decided to go chop wood in the middle of the night! -

wiyosaya I have to say that I, being a potential customer, am a bit concerned that "no one knows how many parts it has." Seems to me that it would be simple enough to use the CAD package that they are using for the project to print out a bill of materials.Reply -

nutjob2 This product still makes me want to throw up. Meanwhile the hype machine is in full swing.Reply -

Puiucs ReplyThis product still makes me want to throw up. Meanwhile the hype machine is in full swing.

It's your own problem. Maybe you didn't have the device on properly or you were using one of the older prototypes.And last but not least: some people just get sick really easily. They need to wait a few years until the technology evolves a bit more. -

photonboy Fascinating, especially if you followed Cormack over the past few years as the tech progressed.Reply

We may have to pass some strict LAWS though or people are going to be playing Frogger for real. -

spectrewind ReplyI have to say that I, being a potential customer, am a bit concerned that "no one knows how many parts it has." Seems to me that it would be simple enough to use the CAD package that they are using for the project to print out a bill of materials.

I have to say that I, being a potential customer, am a bit concerned that "no one knows how many parts it has." Seems to me that it would be simple enough to use the CAD package that they are using for the project to print out a bill of materials.

I have to say that I, being a potential customer, am a bit concerned that "no one knows how many parts it has." Seems to me that it would be simple enough to use the CAD package that they are using for the project to print out a bill of materials.

My opinion, you can relax on this point.

A lot of manufacturing processes outsource various assembly pieces to sub-contractors/companies that mfg just one licensed/proprietary/protected part.. The PCBAs that work with constellation tracking are probably a subset of the grouping of materials. Controllers for video, backlighting, audio components, gyroscope. The XBOX controller MS is shipping with it is probably protected as well.

I'm betting we're dealing with multiple, possibly protected, CAD projects here. -

eldragon0 ReplyI have to say that I, being a potential customer, am a bit concerned that "no one knows how many parts it has." Seems to me that it would be simple enough to use the CAD package that they are using for the project to print out a bill of materials.

I hope you realize this was a joke. It was intended as a shot of comical relief. They know every single part down to it's vertisies; and they know exactly how many parts there are. That's why they are in their positions and not some other smuck. Everyone on the Oculus team is passionate about their creation. -

eldragon0 ReplyThis product still makes me want to throw up. Meanwhile the hype machine is in full swing.

So you've tried the CV1?

Most Popular