AI data centers are swallowing the world's memory and storage supply, setting the stage for a pricing apocalypse that could last a decade

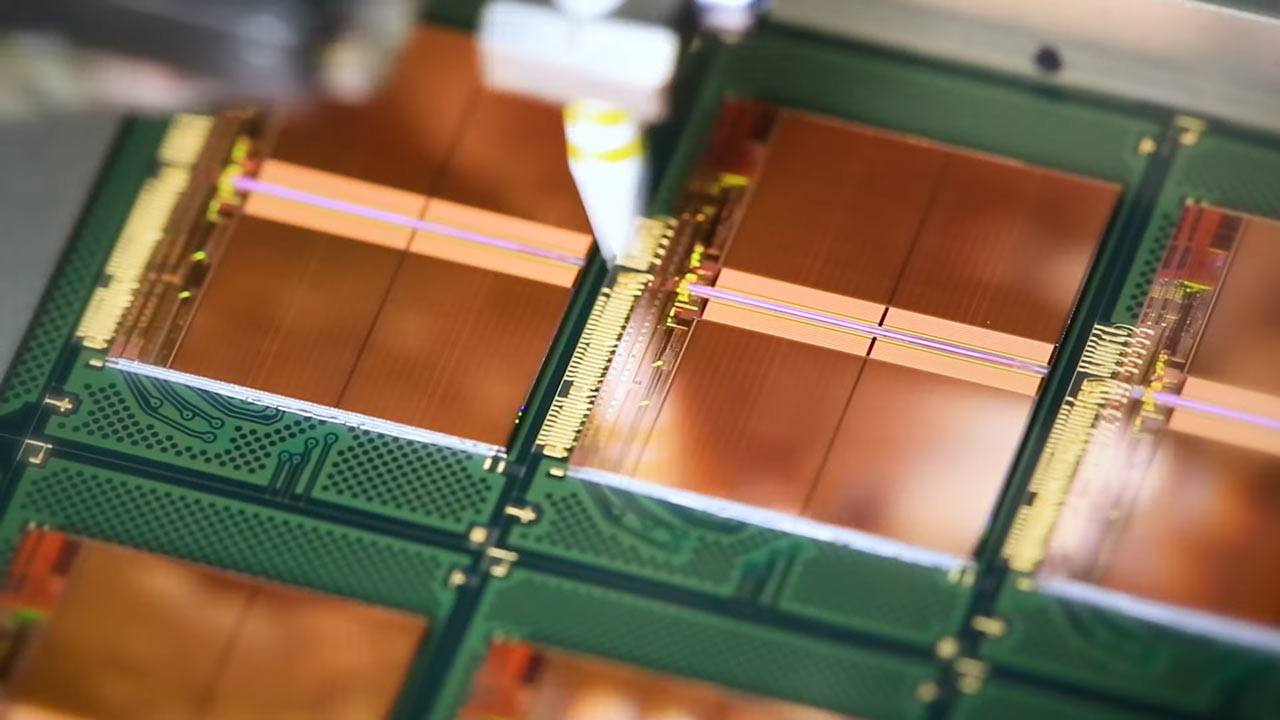

Once-cheap SSDs, DRAM, and HDD prices are climbing fast as AI demand and constrained supply converge to create the tightest market in years.

This free-to-access article was made possible by Tom's Hardware Premium, where you can find in-depth news analysis, features and access to Bench.

Nearly every analyst firm and memory maker is now warning of looming NAND and DRAM shortages that will send SSD and memory prices skyrocketing over the coming months and years, with some even predicting a shortage that will last a decade.

The shortages are becoming impossible to ignore, and warnings from the industry are growing dire, as the voracious appetite of AI data centers begins to consume the lion's share of the world's memory and flash production capacity.

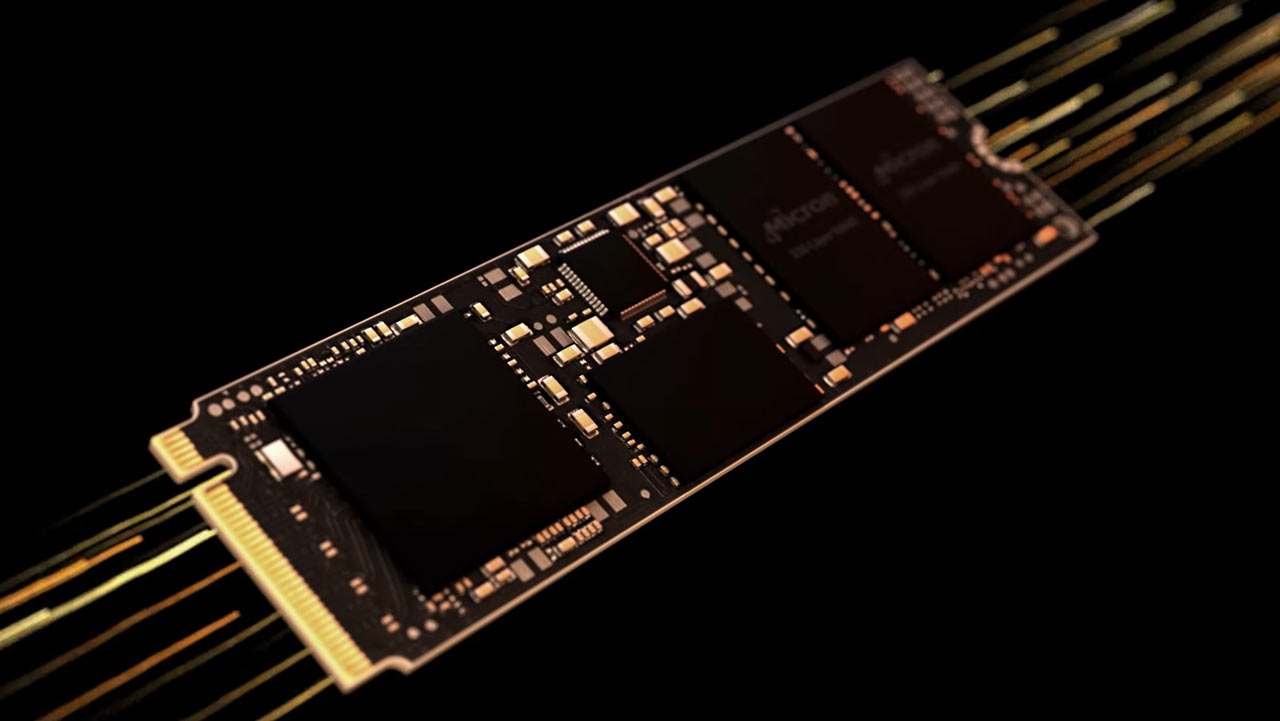

For the better part of two years, storage upgrades have been a rare bright spot for PC builders. SSD prices cratered to all-time lows in 2023, with high-performance NVMe drives selling for little more than the cost of a modest mechanical hard disk. DRAM followed a similar trajectory, dropping to price points not seen in nearly a decade. In 2024, the pendulum swung firmly in the other direction, with prices for both NAND flash and DRAM starting to climb.

The shift has its roots in the cyclical nature of memory manufacturing, but is amplified this time by the extraordinary demands of AI and hyperscalers. The result is a broad supply squeeze that touches every corner of the industry. From consumer SSDs and DDR4 kits to enterprise storage arrays and bulk HDD shipments, there's a singular throughline: costs are moving upward in a convergence that the market has not seen in years.

From glut to scarcity

The downturn of 2022 and early 2023 left memory makers in dire straits. Both NAND and DRAM were selling below cost, and inventories piled up. Manufacturers responded with drastic output cuts to stem the bleeding. By the second half of 2023, those reductions had worked their way through to sales channels. NAND spot prices for 512Gb TLC parts, which had fallen to record lows, rose by more than 100% in the span of six months, and contract pricing followed.

That rebound quickly showed up on retail shelves. Western Digital’s 2TB Black SN850X sold for upwards of $150 in early 2024, while Samsung’s 990 Pro 2TB went from a holiday low of around $120 to more than $175 within the same timeframe.

The DRAM market lagged behind NAND by a quarter, but the pattern was the same. DDR4 modules — clearance items in 2023 — experienced a supply crunch as production lines began to wind down. Forecasts for Q3 2025's PC-grade DDR4 products were set to jump by 38-43% quarter-over-quarter, with server DDR4 close behind at 28-33%.

Even the graphics memory market began to strain. Vendors shifted to GDDR7 for next-generation GPUs, and shortfalls in GDDR6 sales inflated prices by around 30%. DDR5, still the mainstream ramp, rose more modestly but showed a clear upward slope.

Hard drives faced their own constraints. Western Digital notified partners in April 2024 that it would increase HDD prices by 5-10% in response to limited supply. Meanwhile, TrendForce recently identified a shortage in nearline HDDs, the high-capacity models used in data centers. That shortage redirected some workloads toward flash, tightening NAND supply further.

AI’s insatiable appetite

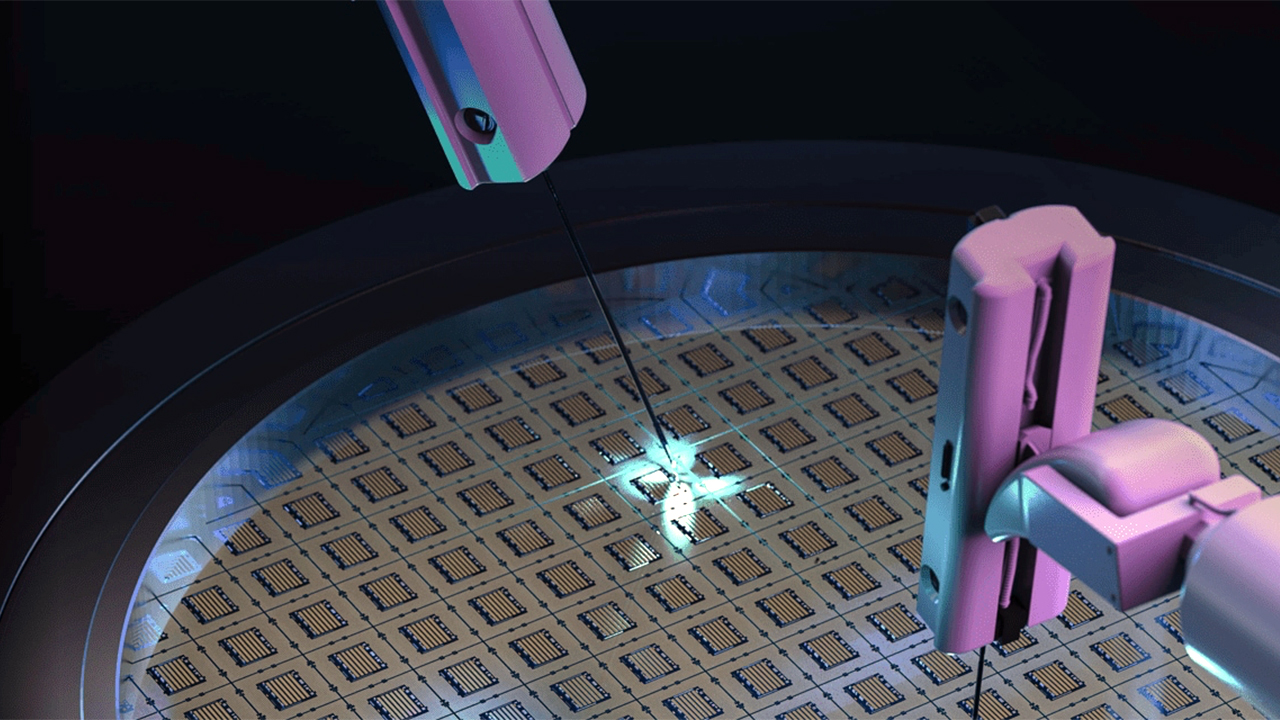

Every memory cycle has a trigger, or a series of triggers. In past years, it was the arrival of smartphones, then solid-state notebooks, then cloud storage. This time, the main driver of demand is AI. Training and deploying large language models require vast amounts of memory and storage, and each GPU node in a training cluster can consume hundreds of gigabytes of DRAM and multiple terabytes of flash storage. Within large-scale data centers, the numbers are staggering.

OpenAI’s “Stargate” project has recently signed an agreement with Samsung and SK hynix for up to 900,000 wafers of DRAM per month. That figure alone would account for close to 40% of global DRAM output. Whether the full allocation is realized or not, the fact that such a deal even exists shows how aggressively AI firms are locking in supply at an enormous scale.

Cloud service providers are behaving similarly. High-density NAND products are effectively sold out months in advance. Samsung’s next-generation V9 NAND is already nearly booked before it's even launched. Micron has presold almost all of its High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) output through 2026. Contracts that once covered a quarter now span years, with hyperscalers buying directly at the source.

The knock-on effects are visible at the consumer level. Raspberry Pi, which had stockpiled memory during the downturn, was forced to raise prices in October 2025 due to memory costs. The 4GB versions of its Compute Module 4 and 5 increased by $5, while the 8GB models rose by $10. Eben Upton, the company’s CEO, noted that “memory costs roughly 120% more than it did a year ago,” in an official statement on the Raspberry Pi website. Seemingly, nothing and no one can escape the surge in pricing.

Shifting investment priorities

A shortage is not simply a matter of demand rising too quickly. Supply is also being redirected. Over the past decade, NAND and DRAM makers learned that unchecked production expansion usually leads to collapse. After each boom, the subsequent oversupply destroyed margins, so the response this cycle has been more restrained.

Samsung, SK hynix, and Micron have all diverted capital expenditure toward HBM and advanced nodes — HBM in particular commands exceptional margins, making it an obvious priority. Micron’s entire 2026 HBM output is already committed, and every wafer devoted to HBM is one not available for DRAM. The same is true for NAND, where engineering effort and production are concentrated on 3D QLC NAND for enterprise customers.

According to the CEO of Phison Electronics, Taiwan’s largest NAND controller company, it’s this redirection of capital expenditure that will cause tight supply for, he claims, the next decade.

“NAND will face severe shortages in the next year. I think supply will be tight for the next ten years,” he said in a recent interview. When asked why, he said, “Two reasons. First… every time flash makers invested more, prices collapsed, and they never recouped their investments… Then in 2023, Micron and SK hynix redirected huge capex into HBM because the margins were so attractive, leaving even less investment for flash.”

It's these actions that are squeezing more mainstream products even tighter. DDR4 is being wound down faster than demand is tapering. Meanwhile, TLC NAND, once abundant, is also being rationed as manufacturers allocate their resources where the money is, leaving older but still essential segments undersupplied.

The same story is playing out in storage. For the first time, NAND flash and HDDs are both constrained at once. Historically, when one was expensive, the other provided a release valve, but training large models involves ingesting petabytes of data, and all of it has to live somewhere. That “warm” data usually sits on nearline HDDs in data centers, but demand is now so high that lead times for top-capacity drives have stretched beyond a year.

With nearline HDDs scarce, some hyperscalers are accelerating the deployment of QLC flash arrays. That solves one bottleneck, but creates another, pushing demand pressure back onto NAND supply chains. For the first time, SSDs are being adopted at scale for roles where cost-per-gigabyte once excluded them. The result is a squeeze from both sides, with HDD prices rising because of supply limits and SSD prices firming as cloud buyers step in to fill the gap.

Why not build even more fabs?

Fabs are being built, but they’re expensive and take a long time to get up and running, especially in the U.S. A new greenfield memory fab comes with a price tag in the tens of billions, and requires several years before volume production. Even expansions of existing lines take months of tool installation and calibration, with equipment suppliers such as ASML and Applied Materials struggling with major backlogs.

Manufacturers also remain wary of repeating past mistakes. If demand cools or procurement pauses after stockpiling, an overbuilt market could send prices tumbling. The scars of 2019 and 2022 are still fresh in their minds. This makes companies reluctant to bet on long-term cycles, even as AI demand looks insatiable today — after all, many believe that we're witnessing an AI bubble.

Geopolitics adds yet more complexity to the conundrum. Export controls on advanced lithography equipment and restrictions on rare earth elements complicate any potential HDD fab expansion plans. These storage drives rely on Neodymium magnets, one of the most sought-after types of rare earth materials. HDDs are one of the single-largest users of rare earth magnets in the world, and China currently dominates the production of these rare earth materials. The country has recently restricted the supply of magnets as a retaliatory action against the U.S. in the ongoing trade war between the two nations.

Even if the capital were available, the supply chain for the required tools and materials is itself constrained. Talent shortages in semiconductor engineering slow the process even further. The net result is deliberate discipline, with manufacturers choosing to sell existing supply at higher margins rather than risk another collapse.

Unfortunately, manufacturers’ approaches to the matter are unlikely to change any time soon. For consumers, this puts an end to ultra-cheap PC upgrades, while enterprise customers will need larger infrastructure budgets. Storage arrays, servers, and GPU clusters all require more memory at a higher cost, and many hyperscalers make their own SSDs using custom controllers from several vendors.

Larger companies, like Pure Storage, procure NAND in massive quantities for all-flash arrays that power AI data centers. Some hyperscalers have already adjusted by reserving supply years in advance. Smaller operators without that leverage face longer lead times and steeper bills.

Flexibility is reduced in both cases. Consumers can delay an upgrade or accept smaller capacities, but the broader effect is to slow the adoption of high-capacity drives and larger memory footprints. Enterprises have little choice but to absorb costs, given the critical role of memory in AI and cloud workloads.

The market should eventually rebalance, but it’s impossible to predict when. New fabs are under construction, supported by government incentives, and if demand growth moderates or procurement pauses, the cycle could shift back toward oversupply.

Until then, prices for NAND flash, DRAM, and HDDs will likely remain elevated into 2026. Enterprise buyers will continue to command priority, leaving consumers to compete for what remains. And the seasonal price dips we took for granted in the years gone by probably won’t be returning any time soon.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our up-to-date news, analysis, and reviews in your feeds. Make sure to click the Follow button.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.

-

LabRat 891 Shouldn't this also mean a *lot* of high-end eWaste and 'surplus' Enterprise equipment in that time? Or, is pretty much everyone demanding their kit be destroyed post-use?Reply -

kameljoe23 I'm weary of people calling AI a bubble. AI is the future and everyone knows it. Sure companies might be overvalued at this time yet their future potential is so great that their valuation deserves what they are today. The demand for hardware and software will will be 10-fold. Large language models might be the tip of the iceberg right now yet there are a number of other AI models out there that will require the same hardware.Reply -

Alvar "Miles" Udell Reply“NAND will face severe shortages in the next year. I think supply will be tight for the next ten years,” he said in a recent interview.

Guess I'll still be rocking this 5950X for another decade then. -

hhuling86 Reply

I have no use for AI nor will I ever, especially if I have to start paying extra on my electricity bill, for instancekameljoe23 said:I'm weary of people calling AI a bubble. AI is the future and everyone knows it. Sure companies might be overvalued at this time yet their future potential is so great that their valuation deserves what they are today. The demand for hardware and software will will be 10-fold. Large language models might be the tip of the iceberg right now yet there are a number of other AI models out there that will require the same hardware. -

ggeeoorrggee Reply

The problem with AI is that the models and the systems that drive them are all derivative (also based on theft). Further the output is generally flawed by an inability to do anything other than mimicry — which leads to repetition of flaws — leading further refinement on the same principle to reach a finer and finer flaw point. Unfortunately, that flaw point continues and becomes harder to locate once fringe cases surface issues. At its root, AI in its current forms doesn’t understand a problem it can’t find in the past and routinely misidentifies dissimilar problems as the same due to an inability to parse nuance.kameljoe23 said:I'm weary of people calling AI a bubble. AI is the future and everyone knows it. Sure companies might be overvalued at this time yet their future potential is so great that their valuation deserves what they are today. The demand for hardware and software will will be 10-fold. Large language models might be the tip of the iceberg right now yet there are a number of other AI models out there that will require the same hardware.

However none of that is the actual bubble. The actual bubble that will drag us all down is, as ever, financial in the way companies are pouring dump trucks of cash into increasingly hungry systems that are not giving anything remotely equivalent in return. As with all financial bubbles, the upper limit comes when there are no more promises to be made, futures to gild, and places to hide massive debt. Just like the dot com, the banking, and the housing bubbles. I wouldn’t be surprised if auto loans are coming up on that soon too. -

Zaranthos It wasn't long ago the articles were about RAM and NAND suppliers cutting production because of lower demand. This to shall pass. Right now most of the world is investing in AI and semiconductor manufacturing. Even Intel suddenly seems to possibly have a future when some thought they were soon dead. There is a lot of new competition in RAM and NAND as well.Reply

There may be some supply constraints that drive prices higher like they have with GPU prices, but all of this is also driving innovation, R&D, and more advanced technologies. Ultimately we'll all benefit, unfortunately a lot of us are going to pay a lot more for electricity before that problem is fixed. If even some of AI ends up being a bubble that bursts then at some point electricity rates should come crashing back down with it as demand for power decreases or supply far exceeds demand. As dump as a lot of AI is right now it should ultimately drive a whole new era of benefits to mankind, if it doesn't kill us all first. Maybe I'll watch Terminator again just in case. :tongueout: -

LinuxRocks Reply

100% This!ggeeoorrggee said:The problem with AI is that the models and the systems that drive them are all derivative (also based on theft). Further the output is generally flawed by an inability to do anything other than mimicry — which leads to repetition of flaws — leading further refinement on the same principle to reach a finer and finer flaw point. Unfortunately, that flaw point continues and becomes harder to locate once fringe cases surface issues. At its root, AI in its current forms doesn’t understand a problem it can’t find in the past and routinely misidentifies dissimilar problems as the same due to an inability to parse nuance.

However none of that is the actual bubble. The actual bubble that will drag us all down is, as ever, financial in the way companies are pouring dump trucks of cash into increasingly hungry systems that are not giving anything remotely equivalent in return. As with all financial bubbles, the upper limit comes when there are no more promises to be made, futures to gild, and places to hide massive debt. Just like the dot com, the banking, and the housing bubbles. I wouldn’t be surprised if auto loans are coming up on that soon too.

AI's biggest problem, as most people see it, is its not smart at all yet! I mean, it only knows what humans feed it, and that is data from the internet... Really? That is not an intelligence at all, that's just a parser.

Now, I use AI to help consolidate searches, because a computer is much faster at collating than I am LOL.

Disclaimer: Im not an AI expert, but we do use it every day to help with Ansible and bash scripting and other code stuffs, and is it helpful, but where I work, we have a couple racks of GPUs and do our own LLMs, we dont rely on Google or xAI because we work in a classified environment and dont have access.

I also use it on my Linux systems at home though LM Studio and find AI to be, again, nothing but a fast information parser.

It doesn't make decisions on anything... In fact, I find I correct it all the time even on xAI and Google, and its very happy to be corrected and reminds me of some little kind that thinks they know everything HAH. -

BloodLust2222 When AI can clean my house, cook and go to work for me is when I will care about AI.Reply -

ggeeoorrggee I forgot my biggest issue with AI: lack of deterministic outcomes.Reply

Combine that with an unknown trust level, it’s like if every junior engineer in my company would produce randomly different, unverifiable content that they might then also lie about.

Basically H.A.L. without access to life support and the airlock.