Micron secures $318 million Taiwanese subsidy for HBM R&D as AI memory arms race intensifies — three-year project aims to develop leading-edge, high-performance memory

Taiwan doubles down on advanced memory by backing Micron’s next-gen HBM development.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Micron has secured another major vote of confidence from the Taiwanese government, winning approval for an additional NT$4.7 billion (approximately $149 million) in subsidies to expand HBM research and development in Taiwan. Combined with an earlier grant awarded in 2021, the total public support now approaches NT$10 billion, or roughly $318 million, making Micron the largest single recipient of Taiwan’s flagship industrial R&D subsidies to date.

The funding, approved by Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs under its A+ Corporate Innovation and R&D Enhancement program, supports a three-year project running from November 2025 through October 2028. Micron’s total budget for the effort is NT$11.75 billion, with the company covering close to 60% of the cost itself.

The goal is to develop and industrialize leading-edge, high-performance, and HBM technologies in Taiwan at a time when HBM has become one of the most strategically constrained components in the global semiconductor supply chain, driven by surging demand from AI accelerators, data center GPUs, and high-performance computing systems.

HBM as strategic infrastructure

HBM has shifted from a niche technology used in a handful of HPC accelerators into a foundational element of modern AI hardware. Unlike conventional DDR or GDDR memory, HBM stacks multiple DRAM dies vertically and connects them through an ultra-wide interface, delivering orders of magnitude more bandwidth per watt.

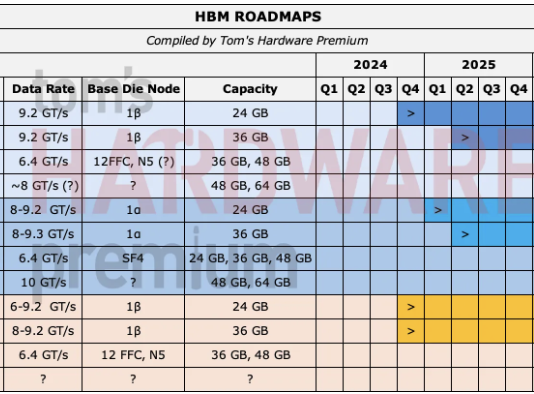

Current HBM3E stacks already provide several terabytes per second of bandwidth, feeding GPUs such as Nvidia’s H200 and AMD’s MI300X without becoming a performance bottleneck. Next-gen HBM4 pushes this further by doubling the interface width to 2048 bits and supporting taller stacks with higher-density dies. In doing so, HBM4-class memory enables larger models, faster training, and more efficient inference without relying solely on brute-force compute scaling.

This, unfortunately, has also turned HBM into a choke point. AI accelerators cannot ship without it, and the ability to produce advanced HBM at scale now directly limits how many high-end GPUs can reach the market. As a result, memory suppliers have found themselves graduating from being interchangeable commodity vendors to fully-fledged semiconductor industry behemoths whose roadmaps influence the entire AI hardware ecosystem.

That explains why governments are increasingly willing to subsidize HBM development, and Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs has been explicit that memory is the missing pillar in its semiconductor ecosystem. The island already dominates advanced logic manufacturing and chip design, but has historically relied on foreign suppliers for cutting-edge memory technology. Supporting Micron’s HBM R&D is a way to anchor that capability locally.

Micron’s position

Micron is the smallest of the three major HBM suppliers by volume, behind SK hynix and Samsung, but it has rapidly closed the tech gap over the past two product generations. Micron’s HBM3E has already been qualified by major accelerator vendors, and the company has publicly stated that its HBM capacity for 2026 is fully booked. The company recently made headlines when it axed its Crucial consumer business to enable the company to focus more on producing HBM and storage devices to feed the AI beast.

SK hynix, meanwhile, currently holds a dominant share of the HBM market and has reportedly committed much of its near-term output to Nvidia, while Samsung is investing aggressively to regain momentum, pushing 12-layer HBM3E and preparing for HBM4 transitions. In that environment, Micron’s ability to accelerate development, improve yields, and bring new stacks to volume production earlier than rivals could materially affect market share.

Taiwan also offers Micron more than just money. The subsidy requires R&D to be conducted locally and encourages collaboration with Taiwanese companies, particularly in equipment, materials, and advanced packaging. That’s key because HBM development is not just about DRAM cell design but also involves through-silicon vias, wafer bonding, thermal management, and increasingly complex interposer and advanced packaging technologies.

Taiwan’s semiconductor supply chain is exceptionally strong in these areas. Locating HBM R&D there shortens feedback loops between design, process development, and manufacturing equipment vendors, which can translate into faster iteration cycles and more predictable ramp-ups.

Implications for Taiwan’s semiconductor industry

From Taiwan’s perspective, this deal is about long-term positioning, with the government estimating that Micron’s DRAM and HBM investments could generate more than NT$800 billion in domestic output value and create over 20,000 direct and indirect jobs. Those numbers are ambitious, but they underscore the scale of economic activity tied to advanced memory manufacturing.

More importantly, HBM development reinforces Taiwan’s role as a system-level semiconductor hub rather than a single-node manufacturing center. As AI hardware becomes more tightly integrated across logic, memory, and packaging, geographic clusters that can support all three gain an advantage. Taiwan already hosts the world’s most advanced logic fabs and a dense network of OSAT and materials suppliers. Adding leading-edge memory R&D to that mix strengthens the entire ecosystem.

There are also the obvious geopolitical elements. Memory supply has become a major concern for both the United States and its allies, particularly as AI hardware increasingly underpins economic and military capabilities. Micron is the only major U.S.-headquartered DRAM manufacturer, so supporting its advanced R&D footprint in Taiwan aligns with broader efforts to diversify and secure critical semiconductor supply chains without concentrating all leading-edge development in a single country.

Ultimately, this subsidy reinforces the broader industry consensus that the HBM shortage is not a transient problem that’s going to resolve itself or be resolved through incremental capacity additions. There’s a serious, structural deficit driven by sustained AI demand and increasing technical complexity — moving from HBM3E to HBM4 brings all new architectures and closer integration with advanced packaging — and the only way to solve it is through solid, calculated R&D; government-backed funding can meaningfully influence how quickly the necessary transitions occur.

By offsetting some of the risk and cost, Taiwan is effectively saying that it thinks HBM will remain a bottleneck well into the second half of the decade, and that it’s a bottleneck worth solving.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.