Nvidia's $20 billion Groq IP deal bolsters AI market domination — hardware stack and key engineer behind Google TPUs included in bombshell agreement

The chip giant is acquiring Groq’s IP and engineering team as it moves to lock down the next phase of AI compute.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Nvidia has announced a $20 billion deal to acquire Groq’s intellectual property. While it's not the company itself, Nvidia will absorb key members of its engineering team, including its ex-Google engineer founder, Jonathan Ross, and Groq president Sunny Madra, marking the company’s largest AI-related transaction since the Mellanox acquisition.

Nvidia’s purchase of Groq’s LPU IP focuses not on training — the space Nvidia already dominates — but inference, the computational process that turns AI models into real-time services. Groq’s core product is the LPU, or Language Processing Unit, a chip optimized to run large language models at ultra-low latency.

Where GPUs excel at large-batch parallelism, Groq’s statically scheduled architecture and SRAM-based memory design enable consistent performance for single-token inference workloads. That makes it particularly well-suited for applications like chatbot hosting and real-time agents, exactly the type of products that cloud vendors and startups are racing to scale.

The deal is structured as a non-exclusive license of Groq’s technology alongside a broad hiring initiative, allowing Nvidia to avoid triggering a full regulatory merger review while still acquiring de facto control over the startup’s roadmap. GroqCloud, the company’s public inference API, will continue to operate independently for now.

Buying time

Groq’s primary selling point is the simplicity of its architecture. Unlike general-purpose GPUs, the company’s chips use a single massive core and hundreds of megabytes of on-die SRAM. It has a static execution model, meaning the compiler pre-plans the entire program path and guarantees cycle-level determinism. The result of that is predictable latency with no cache misses or stalls.

In a benchmark of the 70B-parameter Llama 2 model, Groq’s LPU sustained 241 tokens per second, and internally, the company has reported even higher speeds on newer silicon. This throughput is achieved not by scaling up in batch size, but by optimizing for single-stream performance. That’s a fairly major distinction for any workloads that are dependent on real-time response rather than aggregate throughput.

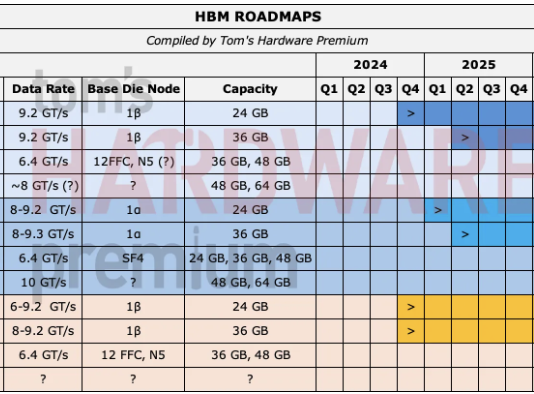

Nvidia’s GPUs, including the upcoming Rubin series, rely on high-bandwidth external memory (GDDR7 or HBM3) and a highly parallel core layout. They scale efficiently for training and large-batch inference, but their performance drops at batch size one. Some of this can be mitigated by software optimization, but Groq’s approach avoids the problem entirely by eliminating external memory latency from the loop.

The acquisition grants Nvidia access to Groq’s entire hardware stack, encompassing the compiler toolchain and silicon design. More importantly, it brings in Groq’s engineering leadership, including founder Jonathan Ross, whose work on Google’s original TPU helped define the modern AI accelerator landscape. With this deal, Nvidia effectively compresses several years of inference-focused R&D into a single integration step.

Strategic containment

Groq had emerged as one of the few companies capable of beating Nvidia on certain inference benchmarks, and its customer-facing cloud product was beginning to gain traction. The LPU’s strong performance in small-batch scenarios made it attractive to developers running generative models, a segment Nvidia has only recently begun to target directly.

By bringing Groq’s IP in-house, Nvidia neutralizes that competition and positions itself to offer a full-stack solution across training and inference. The company can now develop systems that pair its high-throughput GPUs with Groq’s low-latency LPUs, leveraging the strengths of each architecture. This will eventually lead to a broader compute portfolio that covers a wider range of model sizes and deployment targets.

It also blocks Groq from falling into the hands of Nvidia’s rivals. AMD and Intel have both been investing in AI accelerators, while cloud hyperscalers such as Google, Amazon, and Microsoft have been ramping up internal chip development. Any of those companies would have benefited from a differentiated inference engine that could challenge Nvidia’s dominance.

Structuring the deal as a licensing agreement rather than a full-blown acquisition with staff retention clauses gives Nvidia flexibility in how it integrates the technology. It also reduces immediate antitrust exposure, a key consideration given the regulatory scrutiny surrounding Nvidia’s past attempts at major acquisitions. But the outcome is effectively the same: Groq is now governed by Nvidia’s roadmap.

A new shape for inference

Groq’s chip isn’t the only architecture optimized for deterministic, low-latency inference. Cerebras’s CS-2 uses a wafer-scale engine with 40 GB of on-chip SRAM to achieve high throughput on large models. SambaNova combines SRAM with external memory to support even larger parameter counts. Meanwhile, Google’s TPUv5 builds on its own internal compiler and memory hierarchy for serving.

What sets Groq apart is the balance of power efficiency and performance on single-sequence workloads. It doesn’t try to host trillion-parameter models; instead, it prioritizes consistent speed and low cost of service — the characteristics that are important for real-world deployment. Nvidia’s GPUs remain best-in-class for training and general-purpose inference, but integrating Groq’s design gives the company a new lever for real-time AI products.

It will be interesting to see what sort of hardware follows this licensing agreement. Because the two architectures are complementary, we’ll almost certainly see an amalgamated hybrid system, with racks of Rubin or H100s for training and large-batch jobs, backed by Groq LPUs for decoding and token generation.

This could also accelerate a shift in how AI compute is provisioned. Rather than one chip to rule them all, inference is becoming a multi-architecture problem. Nvidia is hoping that, by owning both the high-throughput and low-latency ends of the spectrum, it can maintain its dominant position even as customer needs diversify.

Meanwhile, GroqCloud continues to operate as a standalone service, with Groq saying in a statement that it “will continue to operate as an independent company.”

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.