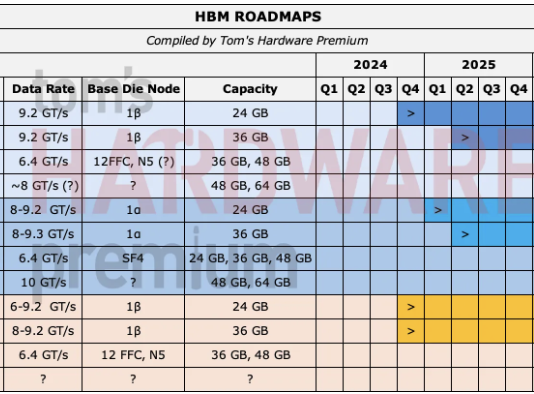

China's reverse-engineered Frankenstein EUV chipmaking tool hasn't produced a single chip — sanctions-busting experiment is still years away from becoming operational

Recreating an entire supply chain is incredibly difficult

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A report this week claimed that a covert laboratory in China had managed to reverse-engineer an extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography scanner, one of the most complex machines on Earth, shocking many industry observers. However, China's 'Frankenstein' EUV chipmaking tool is known to be cobbled together from many disparate parts and not fit for manufacturing of any sort. In fact, the experiment hasn't even produced a single chip.

When you have been around long enough in the tech industry, one thing that you learn is that all the breakthroughs that happen around are a result of years, if not decades, of hard work of multiple teams. Then, bringing these breakthroughs to mass production takes another five to 10 years, depending on the involvement of big companies like Intel, which are well-suited to translate scientific innovations into production as quickly as possible. Here's why China's experimental EUV machine is still many years away from producing even a single chip.

Can you steal a blueprint for an EUV tool?

The report about a reverse-engineered EUV lithography machine that produces EUV radiation using the same CO2 laser-produced plasma (LPP) method that ASML uses reminded me of a scene in Christopher Nolan's movie 'Oppenheimer', when Lewis Strauss implies that the blueprints of the American nuclear bomb were stolen based on the fact that Russians have used a plutonium implosion device, like the one built in Los Alamos.

Indeed, blueprints and detailed scientific information from the U.S. Manhattan Project were stolen by Soviet spies. But while in the case of the atomic bomb, there were actual blueprints and detailed scientific information in Los Alamos, so seven convicted Russian spies had somewhere to steal from, there is no single detailed blueprint of an EUV scanner, according to a source with knowledge of the matter.

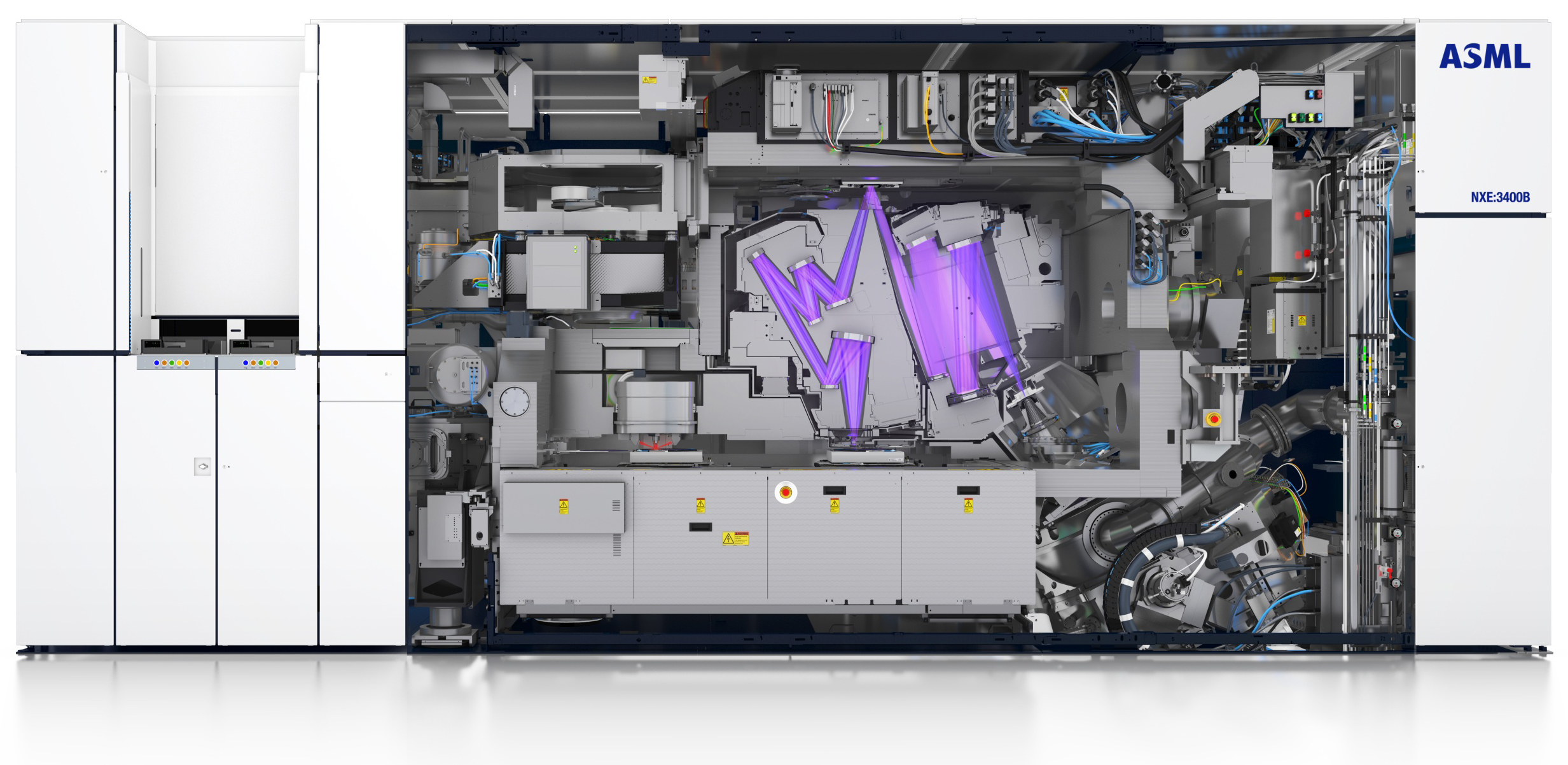

This may be correct, as the current Twinscan NXE platform is a product developed worldwide by a constellation of partners. While there is no doubt that China has a widespread spy network, stealing blueprints from multiple ASML facilities worldwide is difficult. What's even more challenging is stealing blueprints of parts from thousands of ASML suppliers worldwide, then assembling a functioning EUV lithography tool.

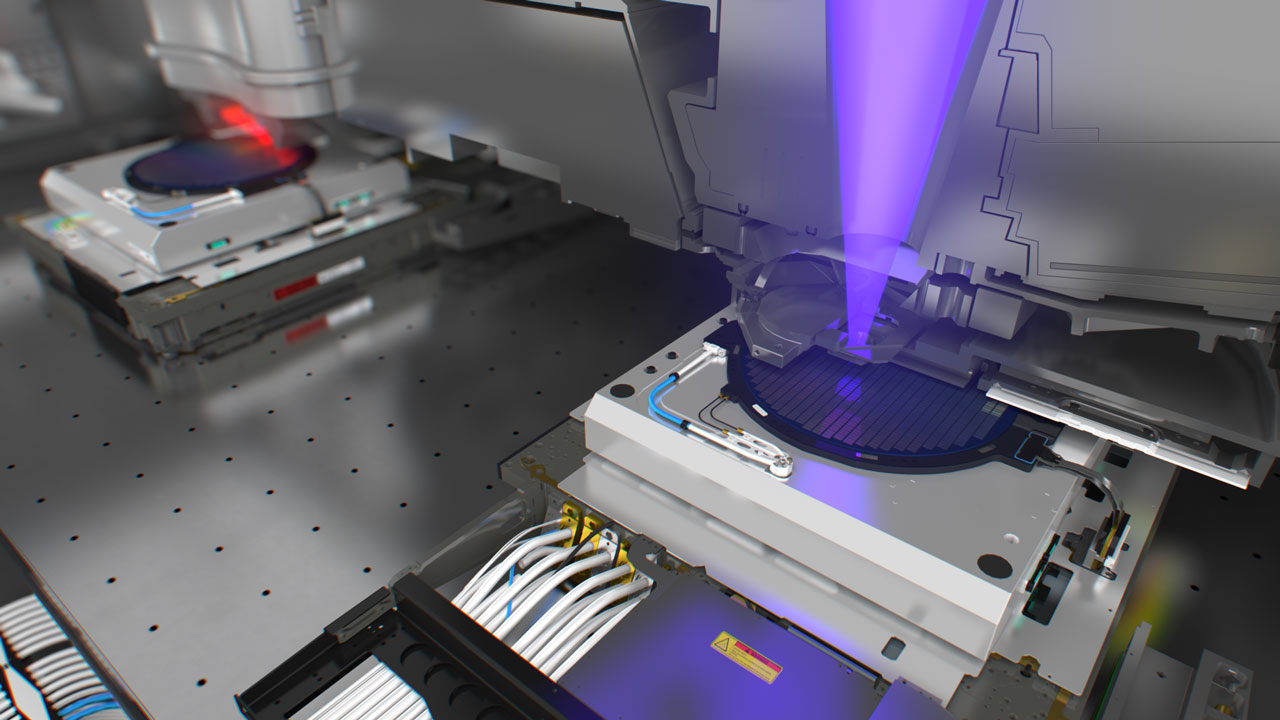

To add some context, Cymer — the inventor of ASML’s EUV LPP-based light source — is an American company (subject to all imaginable export controls) that ASML acquired in 2012. Cymer is now an internal part of the ASML supply chain. It provides the complete EUV light-generation subsystem, including the LPP source (which generates 13.5-nm radiation), a high-performance CO2 laser system, tin-droplet generation with a targeting unit, a debris-mitigation unit, and the EUV radiation collector. The hardware itself is precious, but so are the associated proprietary firmware, control software, and diagnostic tools required to continuously deliver stable, high-performance EUV radiation to the scanner for high-volume manufacturing (HVM).

Even then, Cymer's EUV source relies on a high-end ultra-precise mirror, coated with multilayer molybdenum-silicon (Mo/Si) stacks developed and made by Carl Zeiss in Germany. Since EUV radiation can be absorbed by almost anything, it also requires specialized mirrors from Carl Zeiss.

Without illuminator optics (which shape and uniform the beam using faceted mirrors) and projection optics (a series of aspheric mirrors for 4X – 8X reduction imaging with sub-nanometer wavefront errors), the EUV source itself is useless in isolation. Even if one can steal blueprints of Carl Zeiss optics, replicating them is hard, if not impossible, because it requires utmost precision, and for now, Carl Zeiss is the only company in the world that can produce such precise optics hardware.

Can you steal an entire high-tech supply chain?

Beyond optics, ASML relies on thousands of suppliers across the United States, Japan, and Europe to deliver critical subsystems, which it then integrates into a single machine.

In the U.S., ASML’s Cymer division develops the laser-produced plasma light source, as mentioned above. Japanese companies supply ultra-precision mechanical components, sensors, and materials, including EUV photoresists, while European firms provide vacuum systems, precision structures, and specialty materials. Each supplier owns proprietary process technology that ASML itself does not fully control, which highlights that EUV lithography is ultimately sustained not by one company, but by an ecosystem whose collective intellectual property and integration experience form one of the deepest and most crucial technological chains in the semiconductor industry.

ASML's key ability is to orchestrate this ecosystem and integrate tens of thousands of externally developed parts with its own hardware and software into a machine that operates at nanometer-scale tolerances in high-volume manufacturing. Therefore, replicating an EUV lithography tool requires far more than copying a scanner's design (which is impossible as there is no single blueprint of an EUV machine and the company does its best to keep knowledge of its engineers the unit compartmentalized): it demands recreating an entire global supplier network, the co-development culture that binds it together through groups such as imec (which no longer works with Chinese clients), and the decades of trial-and-error that transformed fragile subsystems into a tool that is widely used for high-volume chipmaking.

Can you even DIY a lithography tool?

Considering the versatility of ASML's scanner design, as well as its omnipresence throughout the industry, there are numerous loopholes in obtaining certain parts of the machinery. Banks or chipmakers usually auction off older lithography equipment, and spare parts for advanced tools can be found on open markets (even eBay yields results for spares).

There is an additional rumor claiming that China intercepted a Cymer EUV radiation source while it was in transit, recorded the part numbers, then obtained them from various sellers or acquired refurbished scrap parts, and assembled a machine in a covert lab. Because not all parts can be acquired on the open market and their condition is unknown, this Frankenstein EUV tool does not work, according to Reuters.

Yet, because ASML's tools are designed to be easily serviced or upgraded in the field and spares appear readily available, Chinese chipmakers — such as SMIC — have managed to upgrade some of their existing tools using components obtained from third parties. For example, they have obtained stage and overlay performance data for the Twinscan NXT DUV lithography tools to make them more suitable for producing chips at advanced nodes, such as 7nm-class process technologies. It goes without saying that such Frankensteined upgrades and tools may not meet all of ASML's stringent standards for quality and reliability. If they increase SMIC's output of advanced wafers by 10%, such modifications may be worth the risk.

The modular nature of ASML's Twiscan platforms simplifies production and upgrade processes. Still, it also means that many of those components can be purchased by unauthorized buyers, such as China-based chipmakers sanctioned by American and European governments. In theory, this means that a Chinese chipmaker could DIY their advanced lithography tools from ASML using components available openly or refurbished in-house, which would, of course, take an incredible amount of time and effort, but would still get them the necessary hardware. However, even obtaining the hardware itself does not guarantee that it functions as intended, as ASML's tools are controlled by proprietary software and firmware that are not publicly available. As a result, even if Chinese specialists obtain the hardware, they will not be able to fully reverse-engineer it to meet ASML's standards.

All in all, it is not surprising that while Chinese scientists have managed to lay their hands on some of the components of ASML's EUV scanner, they have struggled to replicate the tool itself, as they lack a supply chain to produce high-tech parts. They also lack software and firmware that control these components, and therefore, a deep understanding of how they function when working in concert.

Anton Shilov is a contributing writer at Tom’s Hardware. Over the past couple of decades, he has covered everything from CPUs and GPUs to supercomputers and from modern process technologies and latest fab tools to high-tech industry trends.