Intel hamstrung by supply shortages across its business, including production capacity — says it will prioritize data center CPUs over consumer chips, warns of price hikes

Not enough Intel 7 capacity, as it seems.

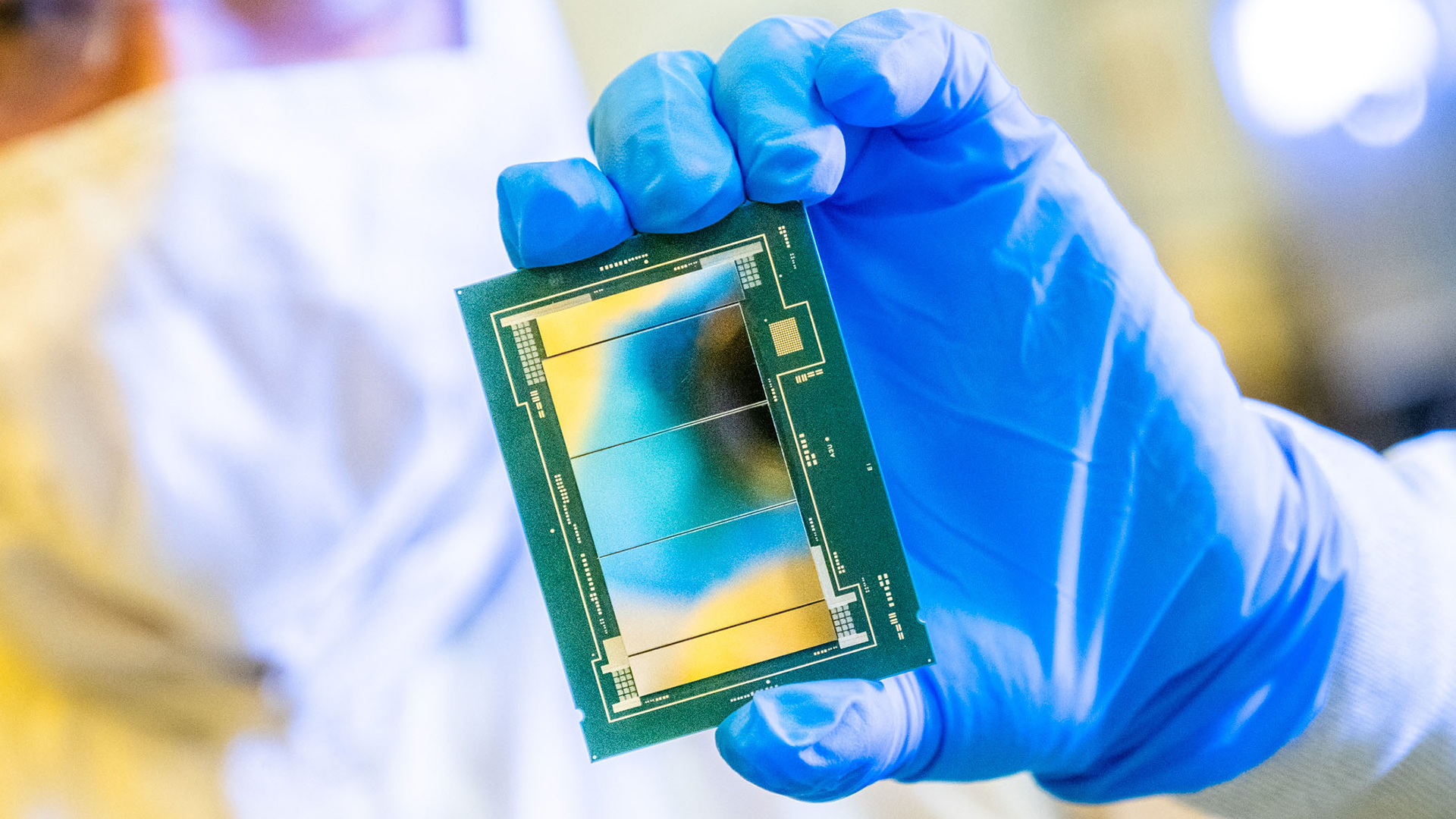

Demand for Intel's processors for client and data center applications was on the rise in the third quarter of 2025, but the company could not fully capitalize on it as it faced numerous supply shortages across its business, which included shortages of its own production capacity and an industry-wide shortage of substrates, which will persist into 2026. The company is prioritizing the supply of data center CPUs, but going forward, it also plans to adjust the pricing of its products, which means increased prices of previous-generation client CPUs.

"Capacity constraints, especially on Intel 10 and Intel 7, limited our ability to fully meet demand in Q3 for both data center and client products," said David Zinsner, chief financial officer of Intel, during the company's conference call with analysts and investors.

Raptor Lake in tight supply

While the Intel 7 (formerly 10nm Enhanced SuperFin) process technology introduced in 2021 – 2022 looks ancient, it still packs quite a punch in terms of performance capability and Intel uses it to produce a host of CPUs, including 13th and 14th Generation Core 'Raptor Lake' CPUs as well as I/O die for Xeon 6 'Granite Rapids' CPUs and 5th Generation Xeon Scalable 'Emerald Rapids' processors that are still in demand. Recently, prices of Intel's Raptor Lake processors rose amid supply constraints up as demand for these CPUs is still high three years after the introduction.

As the company has no plans to expand capacities for previous-generation nodes, but foresees demand for Intel 7 and Intel 10-based products to remain strong in the coming quarters, it expects these CPUs to be in short supply well into 2026. Furthermore, to capitalize on it, Intel intends to adjust pricing and produce more high-end SKUs.

"Given the current tight capacity environment, which we expect [to] persist into 2026, we are working closely with customers to maximize our available output, including adjusting pricing and mix," said Zinsner.

As for Intel 10 (formerly 10nm SuperFin), it is hard to tell which of Intel's broadly available CPUs use it, but Intel probably ships a boatload of long-life-cycle products made using this technology under long-term supply contracts.

Diverting wafers to data center CPUs

As Intel's Xeon 6 'Granite Rapids' uses an I/O die made on Intel 7 process technology, insufficient capacity hits the company's ability to ship enough expensive data center processors. On the one hand, this might be good news for Intel as demand for its server CPUs is back and it can sell them without a discount or even at a higher price. However, if it does not have enough I/O dies, it cannot ship processors at all. Therefore, it has to divert capacity to data center CPUs, thus cutting the supply of client CPUs, which is one of the reasons why Raptor Lake processors got more expensive recently and will likely gain price in the coming months.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

"[In Q4] we expect [client computing group] to be down modestly and [data center and AI group] [to be] up strongly sequentially as we prioritize wafer capacity for server shipments over entry-level client parts," said Zinsner.

Intel's decision to sacrifice some lower-end client CPU volume to keep server CPU customers supplied — particularly hyperscalers and AI infrastructure buyers — has a great rationale as data center CPUs are sold at thousands of dollars a unit, whereas even the highest-end client CPU is hardly sold at $500 - $600. Given the cost of semiconductor fabs and limited production capacity at Intel's 7-capable lines, Intel's management is forced to triage output toward the most profitable products.

Shortages are here to last

In addition to insufficient Intel 7-capable capacity, Intel also blames the shortage of substrates used for CPU packages for the tight supply of its processors, which further complicates the company's supply chain.

" There is also shortages even beyond our specific challenges on the foundry side," said Intel CFO. "I think there's widely reported substrate shortages, for example. So, I think the demand, you know, there is a lot of caution coming into the year, I think across the board."

In general, Intel warns that shortages of its processors will persist through 2026. On the client side, this is conditioned by the slow 18A ramp and decent demand for Raptor Lake processors, whereas on the data center side, it will be driven by insufficient Intel 7 capacity amid the continuous ramp of Xeon 6-series products. The shortages are expected to worsen in Q1, but then there may be some relief.

"We may actually be at our peak in terms of shortages in the first quarter because we have lived through the Q3 and Q4 with a little bit of inventory to help us and just cranking the output as much as we could with the factory," said Zinsner.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our latest news, analysis, & reviews in your feeds.

Anton Shilov is a contributing writer at Tom’s Hardware. Over the past couple of decades, he has covered everything from CPUs and GPUs to supercomputers and from modern process technologies and latest fab tools to high-tech industry trends.

-

bit_user I wonder if the limited Intel 7 capacity has anything to do with the absence of the 12P + 0E Bartlett Lake CPUs.Reply -

shady28 Alder Lake/Raptor Lake were the last and best of the monolithic processors. They still compete today, even though the latest models are now over 2 years old.Reply -

bit_user Reply

Zen 5 does well against them and shows that a CPU doesn't have to be monolithic to have good latencies. And that's even before AMD adopted something akin to Intel's EMIB.shady28 said:Alder Lake/Raptor Lake were the last and best of the monolithic processors. They still compete today, even though the latest models are now over 2 years old.

Intel simply flubbed the SoC architecture in Meteor Lake and Arrow Lake sadly inherited those mistakes. Panther Lake finally fixes it, although we'll have to wait another year for Nova Lake to bring those solutions to the desktop. -

shady28 Replybit_user said:Zen 5 does well against them and shows that a CPU doesn't have to be monolithic to have good latencies. And that's even before AMD adopted something akin to Intel's EMIB.

Intel simply flubbed the SoC architecture in Meteor Lake and Arrow Lake sadly inherited those mistakes. Panther Lake finally fixes it, although we'll have to wait another year for Nova Lake to bring those solutions to the desktop.

Zen 5 is on N4, i.e. a 2nd or 3rd generation 5nm node.

Raptor Lake is on Intel 7, which is essentially equivalent to N7

Excluding the X3D parts, Raptor Lake still generally beats normal Zen 5 in both games and productivity. Even the 9950X merely trades blows to the 14900K in productivity, while losing in most games.

So I don't think that proves anything of the sort. It shows that going with tiles \ chiplets regresses performance in many if not most workloads by nearly a full node generation.

And it shouldn't be a surprise, tiles and chiplets are there to improve yield while providing CPU design flexibility (more chiplets/cores, do I put a 4EU GPU on this or an 8 or a 12, do I give this 4 E cores or 12, etc). They are not there for performance. -

bit_user Reply

Your point was monolithic vs. chiplet/tile. Zen 5 has memory latency that's somewhat comparable to Raptor Lake and far better than Arrow Lake. That shows the issue isn't really one of monolithic vs. chiplets/tiles, but rather that Intel just made some bad design choices, when they created the SoC architecture of Meteor Lake & Arrow Lake.shady28 said:Zen 5 is on N4, i.e. a 2nd or 3rd generation 5nm node.

Raptor Lake is on Intel 7, which is essentially equivalent to N7

Games are low-IPC workloads, where Raptor Lake's clockspeed advantage wins the day. AMD doesn't design its CPUs to clock as high, because they share the same silicon with their mainstream server CPUs, where efficiency & scalability targets would rule out anything like the what desktop CPUs can do. So, it makes sense for them to instead focus on designs with slightly lower peak clockspeeds and higher IPC.shady28 said:Raptor Lake still generally beats normal Zen 5 in both games and productivity. Even the 9950X merely trades blows to the 14900K in productivity, while losing in most games.

Productivity-wise, I don't know what you're talking about, because 9950X wins at:

Source: https://www.techpowerup.com/review/intel-core-ultra-9-285k/

Yeah, I used data from the 285K launch review, in order to avoid the problems reviewers initially had with Zen 5.

You forget about one factor: cost. Chiplets are there as a cost-saving measure, so that parts of the CPU that don't need the latest node don't cost as much. By saving money in some places, more money can be spent elsewhere. Every one of these products is built to hit a certain price target. If you just fab the entire chip on the latest node, then you'd have to cut corners somewhere. Maybe in cache sizes or core complexity, and that would affect performance.shady28 said:And it shouldn't be a surprise, tiles and chiplets are there to improve yield while providing CPU design flexibility (more chiplets/cores, do I put a 4EU GPU on this or an 8 or a 12, do I give this 4 E cores or 12, etc). They are not there for performance. -

shady28 Replybit_user said:Your point was monolithic vs. chiplet/tile.

Thanks for reminding me, I had forgotten...

bit_user said:Zen 5 has memory latency that's somewhat comparable to Raptor Lake and far better than Arrow Lake. That shows the issue isn't really one of monolithic vs. chiplets/tiles, but rather that Intel just made some bad design choices, when they created the SoC architecture of Meteor Lake & Arrow Lake.

<snip a bunch of blather about straw men>

Zen 4/5 along with Zen 2 and Zen 3 along with Arrow Lake, Meteor Lake, and Lunar Lake can all be said to have latency issues compared to monolithic designs like Raptor Lake, or Comet Lake for that matter.

Despite your attempt to turn this into Arrow Lake vs Zen 5, I wasn't talking about Intel vs AMD, nor was I talking about the 285K.

I was talking about tiles/chiplets vs monolithic.

Some quotes and sources on this topic.

"On-chip communication is faster in monolithic designs because the components are physically closer, resulting in lower latency and better overall system performance."

"Monolithic designs often offer superior performance due to the close proximity of components. This proximity reduces signal latency and power consumption, making monolithic chips ideal for high-performance computing."https://resources.pcb.cadence.com/blog/2023-chiplet-vs-monolithic-superior-semiconductor-integration

"The issue with chiplets is that it adds a latency, increases power consumption in addition to the extra cost the interconnects brings."

"On GPUs, the need for extremely low latency has slowed down the adoption of chiplets."https://www.overclock.net/threads/people-keep-saying-chiplets-are-the-future-but-this-just-doesnt-make-any-sense.1801831/

"MCMs with long traces between the CPUs add significant latencies for inter-core communication compared to packing all of these cores in monolithic dies."

https://blog.apnic.net/2023/11/07/chiplets-the-inevitable-transition/

"Although chiplet-based chips can cut (recurring engineering) costs to half, they may give away over a third of the monolithic performance."https://research.chalmers.se/publication/546843/file/546843_Fulltext.pdf

I really shouldn't need to continue at this point. -

bit_user Reply

No, it wasn't. I addressed your points and can back up any of them you want me to. I think you either know or suspect I'm actually right, so it's fine with me if you want to drop them. However, don't accuse me of strawmen when they're not.shady28 said:<snip a bunch of blather about straw men>

Oh, I'm not concerned with what they "can be said to have". People can "say" anything. I'm concerned with actual data, which shows that Ryzen 9000 is competitive with Raptor Lake on DDR5 latency.shady28 said:Zen 4/5 along with Zen 2 and Zen 3 along with Arrow Lake, Meteor Lake, and Lunar Lake can all be said to have latency issues compared to monolithic designs like Raptor Lake, or Comet Lake for that matter.

Source: https://chipsandcheese.com/p/examining-intels-arrow-lake-at-the?utm_source=publication-search

You misunderstand. I didn't cite data from the 285K review for the purpose of comparing against the 285K. If you actually look at the charts I included, they all had data for Ryzen 9000 and Raptor Lake. The reason I grabbed the charts from that review was as an easy way to get the latest data on each CPU, not because I was trying to shift the topic to the 285K.shady28 said:Despite your attempt to turn this into Arrow Lake vs Zen 5, I wasn't talking about Intel vs AMD, nor was I talking about the 285K.

Why would I care about random quotes, in the abstract, when we're talking about real world implementations that can be quantitatively measured and compared?shady28 said:Some quotes and sources on this topic.

"On-chip communication is faster in monolithic designs because the components are physically closer, resulting in lower latency and better overall system performance."

"Monolithic designs often offer superior performance due to the close proximity of components. This proximity reduces signal latency and power consumption, making monolithic chips ideal for high-performance computing."https://resources.pcb.cadence.com/blog/2023-chiplet-vs-monolithic-superior-semiconductor-integration

One can talk in generalities all day long, but that ignores what can be achieved via concerted optimization, as AMD has been progressively doing since the days of Zen 2. What matters isn't whether chiplets pose hurdles, but how well you can overcome them, when you really try.

It would be pointless to try, unless you have data. General quotes don't prove anything.shady28 said:I really shouldn't need to continue at this point. -

shady28 Replybit_user said:No, it wasn't. I addressed your points and can back up any of them you want me to. I think you either know or suspect I'm actually right, so it's fine with me if you want to drop them. However, don't accuse me of strawmen when they're not.

I just linked you to a university study of the two approaches, yet you insist on your AMD vs Intel blather.

bit_user said:Oh, I'm not concerned with what they "can be said to have". People can "say" anything. I'm concerned with actual data, which shows that Ryzen 9000 is competitive with Raptor Lake on DDR5 latency.

Source: https://chipsandcheese.com/p/examining-intels-arrow-lake-at-the?utm_source=publication-search

You are talking about main system RAM latencies.

You are also linking to an Intel tile vs AMD chiplet article.

Once again:

I simply stated that monolithic is inherently faster than tiles/chiplets, all else being equal.

Arrow Lake is not monolithic.

bit_user said:You misunderstand. I didn't cite data from the 285K review for the purpose of comparing against the 285K. If you actually look at the charts I included, they all had data for Ryzen 9000 and Raptor Lake.

They only have that for DRAM. They do not include Raptor Lake for L2/L3 nor most importantly CPU to CPU.

bit_user said:The reason I grabbed the charts from that review was as an easy way to get the latest data on each CPU, not because I was trying to shift the topic to the 285K.

You've been talking about 285K vs Zen 5 the entire time. Where are your comments about Raptor Lake vs Zen 5?

Or more appropriately, Raptor Lake vs its contemporary Zen 3 on similar process nodes?

bit_user said:Why would I care about random quotes, in the abstract, when we're talking about real world implementations that can be quantitatively measured and compared?

Because most are from professional trade publications and one is from a university study on the topic at hand : Monolithic vs Disaggregated

bit_user said:One can talk in generalities all day long, but that ignores what can be achieved via concerted optimization, as AMD has been progressively doing since the days of Zen 2. What matters isn't whether chiplets pose hurdles, but how well you can overcome them, when you really try.

No, the point is that in order to compete against monolithic designs AMD needed an entire node advantage.

Compare Raptor Lake and Alder Lake vs Zen 3, all on N7 / Intel 7 similar nodes and the difference becomes crystal clear.

Unless your judgement is clouded, as yours clearly is.

bit_user said:It would be pointless to try, unless you have data. General quotes don't prove anything.

As I said, there's an entire university study including simulation examples in those links.

From that study:

Multi-Chiplet vs. Monolithic vs. Ideal: Figure 4 shows,per mix of programs, the average performance (IPC), averagepacket latency, average memory access time, and the breakdown of DRAM accesses for the default configuration of a 4-chiplet system as well as for the equivalent 16-core monolithic and ideal systems. The chiplet-based system is able to maintain only 43%-75% of the monolithic performance and on average 58%, as shown in Figure 4(a). Compared to the ideal system, which is 24% faster than the monolithic, and its LLC misses always go to the closest HBM, the chiplet-based system is 54% slower.

-

bit_user Reply

Huge numbers of variables exist in any silicon implementation and there are lots of design choices that weigh on final performance. It's not like you can mathematically prove that any chiplet-based design will perform worse than any monolithic design, hence no study is authoritative.shady28 said:I just linked you to a university study of the two approaches,

Again, the fact that you try to dismiss my reply as "blather" just indicates that you're incapable of addressing it on the merits. Either way, you lose. But, one way certainly looks worse than the other.shady28 said:yet you insist on your AMD vs Intel blather.

Right, because cache & memory latency are the dependent variables overwhelmingly determinitive of real-world performance.shady28 said:You are talking about main system RAM latencies.

I've shown that the inherent downsides of a chiplet-based design aren't insurmountable. That seems to be the key question.shady28 said:Once again:

I simply stated that monolithic is inherently faster than tiles/chiplets, all else being equal.

As I've said, all else is never equal. You simply cannot remove practical considerations, like price, from the picture.

Nobody said it was.shady28 said:Arrow Lake is not monolithic.

Now, you're confused, because I was referring to the TechPowerUp "productivity" charts.shady28 said:They only have that for DRAM. They do not include Raptor Lake for L2/L3 nor most importantly CPU to CPU.

However, Chips & Cheese does have latency data on the cache hierarchies - just not in the table I quoted.

And no, "CPU to CPU" (by which I think you mean core-to-core) latency is not most important. In fact, cores exchange data quite a bit less than they access data in their local cache hierarchy or DRAM. The prominence of those core-to-core latency charts gives a misleading perception of its performance. The real reason why people run those sorts of tests is to divine the interconnect topology and see what kinds of details they can tease out about the cache coherency mechanism, etc.

A multi-threaded program where the cores frequently exchange data would be rife with performance-robbing scalability and lock contention problems, because exchange of data needs to be coordinated. So, skilled programmers try to thread their programs in ways that limit the frequency of data-sharing, as much as possible.

No, reread the first sentence of post #6, where I pointed out that Zen 5 (by which I meant Ryzen 9000), has memory latency competitive with Raptor Lake. I went on to reply to your points about Raptor Lake with productivity data that included both Ryzen 9950X and i9-14900K.shady28 said:You've been talking about 285K vs Zen 5 the entire time. Where are your comments about Raptor Lake vs Zen 5?

The impact of node choice on DRAM latency is minimal, yet DRAM latency is the most important performance parameter impacted by Ryzen's chiplet-oriented architecture. Furthermore, if you're not convinced by that, consider that Ryzen 9000's I/O Die is implemented on TSMC N6, which has comparable transistor gate pitch and metal pitch as Intel 7. That's also where half of the infinity fabric is implemented, which requests & data must traverse on their way between the cores and DRAM.shady28 said:Or more appropriately, Raptor Lake vs its contemporary Zen 3 on similar process nodes?

As I previously explained, AMD's chiplet-based desktop CPUs are not exclusively or even primarily designed for the desktop. They don't have the luxury of optimizing for clock speed, like Intel does, because that would be transistor-intensive and do little for their primary server market.shady28 said:No, the point is that in order to compete against monolithic designs AMD needed an entire node advantage.

You're treating these CPUs as if they have identical design objectives and the only things that differ are chiplet vs. monolithic and process node. This could not be further from the reality. They have countless architectural differences at all scales, and much of that derives from differences in their design objectives and the consequent architectural approaches.

From the first Zen CPUs, AMD focused on scalability, first and foremost. That also came at the expense of clock speed and indeed incurred a latency penalty, but it's one they've worked to minimize as the product line evolved. To see how far that evolution has progressed, we need to look at the latest incarnation, which is Ryzen 9000.

Again, this misses the point. Their simulation bakes in numerous assumptions and holds things invariant that wouldn't be, between real world implementations.shady28 said:As I said, there's an entire university study including simulation examples in those links.

Furthermore, the main thing those numbers tell me is that those researchers have no clue how to design a scalable chiplet-oriented CPU. BTW, AMD does make monolithic Zen CPUs. They also make single- and double- CCD chiplet CPUs, and their clock-normalized scaling is nothing like that bad! Your quote also indicates that it's a Zen 1-style NUMA architecture, so of very limited relevance to anything of AMD's which came after, which just goes to show why you can't blindly apply whatever you read in one research paper to some situation that looks kinda similar, if you ignore basically all of the particulars.

If you want to know how well the impact of a chiplet-based SoC architecture can be mitigated, I've already cited that. If you want something else, then I'm not sure I can help you. -

DS426 Intel has made pricing quite aggressive on Raptor Lake and RL Refresh, so they kind of did this to themselves, lol; I mean, are they after revenues or maintain margin, because my understand was the latter.Reply

I previously mentioned that Intel doesn't even need to have huge capacity on a leading-edge node to maintain good profits -- they just need customers (including Intel as an IFS customer), ensuring fab capacity is close to 100%, and balancing scaling fabs that R&D costs on new nodes is covered by fab revenues. Yes, TSMC makes gobs of money and then can reinvest hundreds of billions of dollars from their sheer scale on leading-edge nodes, but I estimate that Intel can turn a nice profit just by following at N-1 and N-2, even if that's not what we all want (as in "we" wanting Intel to be a TSMC fighter and not a TSMC shadow).