Early Verdict

The Z370 Taichi performs well and has great features for its price. Unfortunately, poor overclocking for this price class paired with poor efficiency and excess heat will make the board unattractive to many enthusiasts.

Pros

- +

Great feature set for the price

- +

Good overall performance

- +

Well-developed software suite

- +

Great layout with minimum shared resources

Cons

- -

Power hungry at full load

- -

Hot at full AVX load

- -

Mediocre overclocking

Why you can trust Tom's Hardware

Features & Layout

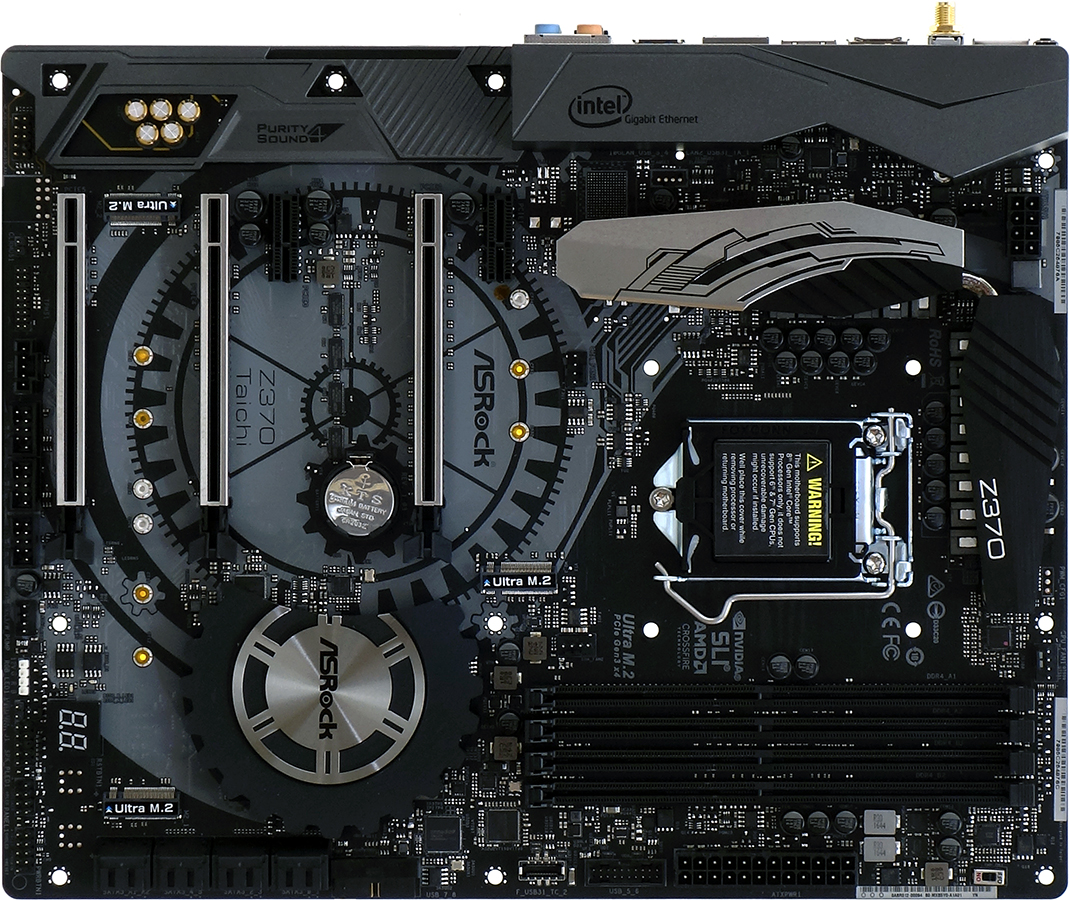

High-end Z-series motherboards typically cost $220-280 and now represent the meaty middle of the enthusiast market. Like the Z270 model that came before it, ASRock’s Z370 Taichi targets the $220 demarcation between mainstream-enthusiast and high-end markets. And like the Z270 model that came before it, ASRock's Z370 Taichi provides a feature set that’s far closer to high-end than mainstream to woo buyers.

The new board replaces its predecessor’s PCH-based x16-length slot with an x1 slot that’s still able to hold longer cards but is less likely to be confused for a high-bandwidth slot, replaces its predecessor’s internally-mounted USB 3.1 port for a now-standard front-panel header, and trades in the black-and-white color scheme for black and grey. (That made building out the features table below as simple as copying the previous version and editing a few cells.)

Specifications

Similarities in features and price between the Z370 Taichi and its predecessor could ease any value assessments, but such assumptions ignore certain aspects of Coffee Lake CPU testing, such as the higher energy requirement of its increased core count. Focusing instead on its counterparts, we find the I/O panel comes up one USB port short of the already-sparse Z370 Aorus Gaming 7, instead dedicating that HSIO resource to its replaceable Wi-Fi controller. I lay the blame of missing USB 2.0 ports at the feet of whiners: These are basically “freebies” from an HSIO resource standpoint, and remain useful for keyboards and mice. I would have taken two, had they been offered.

The Z370 Taichi also adds an I/O panel CLR_CMOS button, which can be a blessing to overclockers who want to make minor changes with their cases closed, or a curse to those whose systems are physically accessible by third parties. Some people just can’t resist pushing buttons. At least this one is small enough that most casual observers won’t notice it.

It’s important to remember that, like the Z270, the Z370 supports a maximum of 30 HSIO pathways, which are divided up as PCIe, SATA, and USB 3.0. All three of the Z370 Taichi’s PCIe x16 slots get their pathways directly from the CPU, so those don’t count. Instead, we’re looking at three M.2 slots (12 pathways), six of the eight SATA ports plus a two-port PCIe-based controller (7 pathways), four I/O panel USB 3.0 ports and a USB 3.0 hub for front-panel headers (5 pathways), two dual-lane USB 3.1 Gen 2 controllers (4 pathways), a two-lane Key-E interface for the Wi-Fi module (2 pathways), a PCIe-based second network controller, and three PCIe x1 slots. Yes, that adds up to 34, and the math explains why four of the SATA ports are redirected to PCIe for M.2. The competing Z370 Aorus Gaming 7 shares two fewer SATA ports only because it instead takes those lanes away from its third x16-length PCIe slot.

The three CPU-fed PCIe slots automatically switch from x16-x0-x0 to x8-x8-x0 and x8-x4-x4 modes when cards are added to the second and third x16-length slots. That configuration allows up to three-way CrossFireX. Configuring two-way SLI requires that the third x16-length slot not be populated, since Nvidia software excludes four-lane slots.

The Z370 Taichi presents few if any layout challenges, as there are two slots of space between the first and second x16-length slot, and the SATA and USB 3.0 headers in front of those all face forward. The front-panel audio header is shoved a little farther into the bottom back corner than we’d like, but if your cable doesn’t reach you should probably scream at the case company. ASRock’s unusual solution to the fitment problem of 110mm M.2 cards was to face two of the slots towards each other, so that builders can use the opposing slot’s 60mm post as the chosen slot’s 110mm post. Using a 110mm M.2 card in one slot limits the opposing slot to 42mm cards, but those of us using 60mm and 80mm M.2 cards can’t be bothered over these details.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

A second group of solder points in front of the FP-Audio header hint at a higher model motherboard using the same PCB to provide alternative (right-angle) connector placement. Moving forward from that point, we find a pair of CLR_CMOS pins with no jumper, a TPM module header, a 5-pin header for Thunderbolt add-in cards, three front-panel USB 2.0 headers, a four-pin fan header with 1.5A capability for high-draw water pumps, an RGB LED header, a pair of jumper pins for forcing the system to boot from the second firmware ROM, a legacy beep-code speaker and AT-style power LED header, and an AC-97 style power/reset/power-led/hdd-led front-panel header that’s been adopted by nearly everyone. A second 1.5A fan power header is found next to the EPS12V connector, and three 1A fan headers are dispersed about the board’s surface.

A switch near the upper-front corner instructs firmware to enable XMP mode. The same setting can be made within the firmware GUI.

The Z370 Taichi includes a driver disc, documentation, four SATA cables (two with a right-angle end), two Wi-Fi antennas, an HB SLI bridge, and an I/O shield.

MORE: Best Motherboards

MORE: How To Choose A Motherboard

MORE: All Motherboard Content