Nexperia’s standoff puts a core part of the chip supply chain under strain — U.S export controls and red tape may threaten consumer continuity without governance

Dutch intervention, China’s retaliation, and widening U.S. controls have turned a major European component supplier into the centre of a three-way dispute.

Nexperia’s position in the semiconductor space has rarely drawn mainstream attention. The Dutch-headquartered firm specializes in the kind of components that disappear into circuit boards by the billions. Yet, its devices sit inside automotive powertrains, industrial controllers, consumer chargers, and virtually every category of electronics.

When the Netherlands moved in October to suspend the authority of Nexperia’s Chinese ownership under its emergency economic-security rules, it set off a sequence of actions in Washington and Beijing, pushed European carmakers into a fresh scramble for parts, and raised wider questions about how long a firm with global roots can operate across competing jurisdictions without becoming a diplomatic flashpoint.

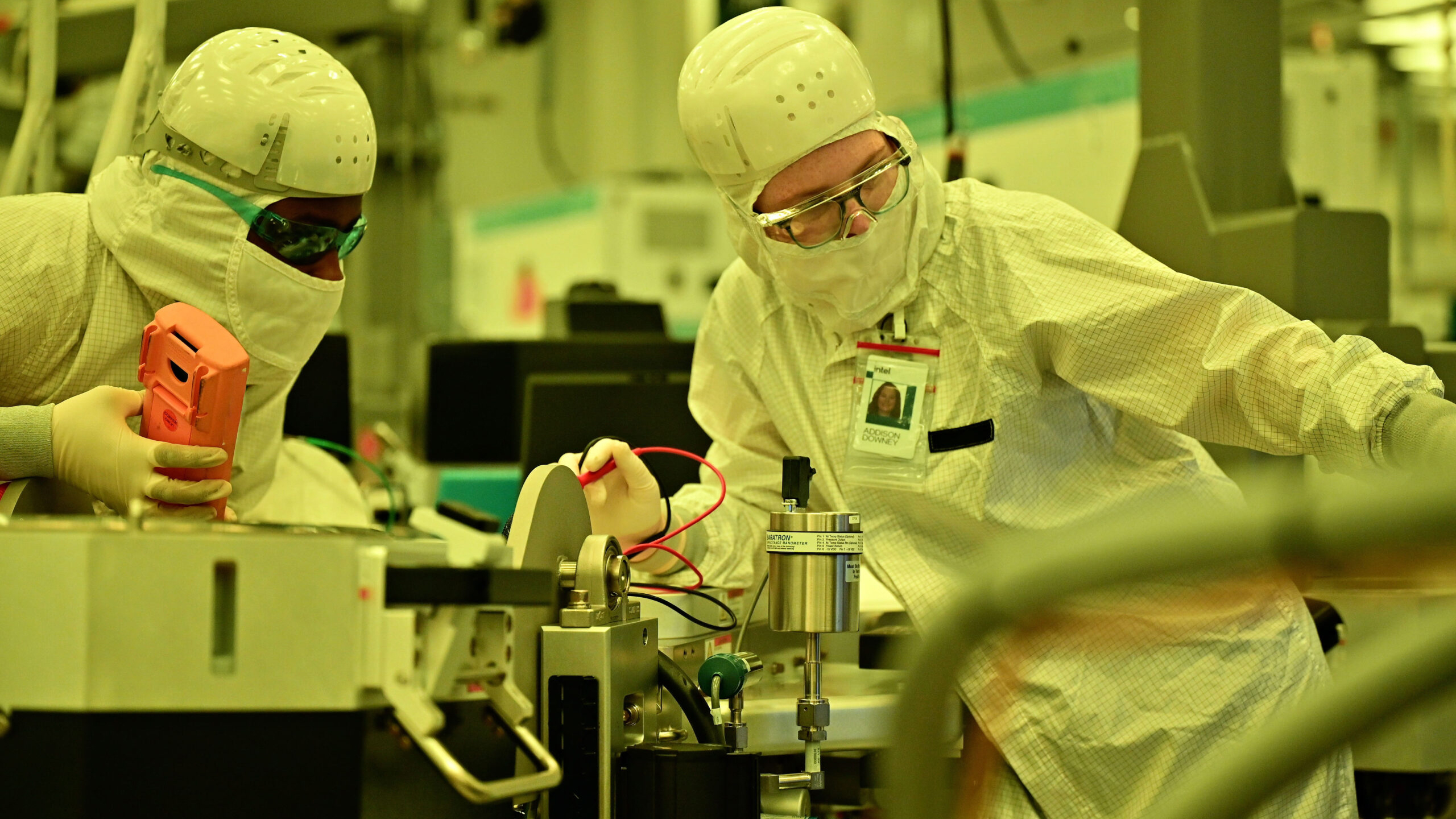

Nexperia was once part of Philips and later NXP, before being acquired privately by China’s Wingtech Technology in 2018. That transaction placed a European industrial supplier within a Chinese electronics conglomerate with links to government-backed investment programmes. Wingtech grew aggressively after the acquisition, and by 2025, Nexperia was producing roughly 110 billion parts per year across its fabs in Hamburg and Manchester and its assembly centres in Asia.

These were not cutting-edge processors, but high-volume power semiconductors, regulators, and discrete logic. They underpin far more sophisticated systems built by others. In sectors such as automotive, a vehicle can contain hundreds of these devices, and the failure of even one category of them cascades into production delays.

That backdrop set the scene for a major reaction when the U.S. added Wingtech to the Entity List in late 2024. The controls did not immediately apply to Nexperia, but Washington made clear that any effort to route restricted technology through its European subsidiary would be treated as a violation. The following summer, the U.S. introduced its “affiliates” rule, extending those restrictions to any majority-owned unit of a listed entity. That swept Nexperia into the same category.

A national intervention with international consequences

On 30 September 2025, the Dutch government invoked the Emergency Goods Availability Act to prevent what it called the “possible relocation” of critical assets and to stabilise Nexperia’s operations inside the EU. The statute had been dormant for decades and had never been used for a semiconductor firm. It allowed The Hague to suspend the authority of Nexperia’s then-CEO, Zhang Xuezheng, who also founded Wingtech, and to transfer voting rights on behalf of the parent company to a court-appointed administrator while an investigation into management practices was opened.

Within days, the provisional measures were upheld by the Dutch courts, and the newly installed leadership halted shipments from Nexperia Europe to its Chinese arm, citing uncertainty over export compliance. Chinese state media responded by arguing that Europe was politicizing a commercial dispute. Beijing then introduced export restrictions on certain finished semiconductors produced by Nexperia’s Chinese subsidiaries and, crucially, on contract manufacturers that handled assembly for European-bound parts. The restrictions came with carve-outs only after several weeks of negotiation.

Several major carmakers warned of renewed shortages of basic power components. In 2021 and 2022, the automotive industry had already become a case study in how a lack of cents-worth parts could stall production of systems costing tens of thousands of dollars. This time, the shortages were rooted not in pandemic shutdowns but in the regulatory limbo created by overlapping national controls. Suppliers scrambling for substitute components reported lead times stretching into the following year. European regulators noted that Nexperia’s parts are embedded across hundreds of platforms, and a sudden loss of even a small share of output would propagate across multiple production lines.

A long build-up

The dispute did not materialise out of nowhere. Nexperia’s 2021 acquisition of Newport Wafer Fab in Wales had already drawn scrutiny from UK officials. Although the deal initially cleared without a review — the UK’s national-security screening regime had not yet begun — it was later called in under the National Security and Investment Act.

In late 2022, the UK ordered Nexperia to divest most of its stake under national security legislation. Nexperia appealed, saying it was "shocked" by the order and arguing that Newport was a mature-node facility with no access to sensitive R&D, and that its acquisition secured local jobs. The standoff remains unresolved. While the UK case is separate from the Dutch intervention, the two episodes show how a firm that once operated quietly across Europe has found itself pulled into a widening set of national priorities.

By 2025, that picture had shifted again. Chinese industrial policy had elevated Wingtech as a model of integration across design, manufacturing, and final assembly. European authorities, faced with their own efforts to strengthen chip supply under the EU Chips Act, regarded this consolidation with more caution. At the same time, the U.S. sought to close what it saw as gaps in its export-control regime. When China responded to the Dutch measures by restricting Nexperia’s outbound shipments, the overlap of these positions hardened.

What this means for the supply chain

The core technical challenge revealed by the Nexperia dispute is that the semiconductor supply chain remains deeply interdependent even in areas considered low risk. Power transistors, diodes, and level shifters do not sit at the centre of geopolitical strategy papers. They are manufactured on older processes, with tooling that predates the EUV era by decades. Because they are simple, they have long been viewed as interchangeable. The past four years have demonstrated that this assumption is fragile. Production is concentrated in a small number of companies, and for certain categories, Nexperia is one of only a handful of suppliers with the scale to support global automotive platforms.

Those characteristics complicate efforts to localise supply or insulate operations from political pressure. When the Dutch government intervened in Nexperia’s management, China’s countermeasures did not target rare earths or advanced lithography equipment, but the output of subcontracting facilities handling packaging and test. It was a reminder that the finishing stages of semiconductor production are often outsourced. Even when front-end wafer capacity sits in Europe, back-end work can be vulnerable to administrative decisions thousands of miles away.

The U.S. sanctions add a further layer. Under the affiliates rule, Nexperia could face the same restrictions as its parent on receiving U.S.-origin technology. This rule is currently suspended for a year as part of the U.S.-China trade deal, but there are no guarantees for the future.

A new normal for cross-border chipmakers?

The partial suspension of the Dutch order in November created space for negotiations, but it did not unwind the deeper issues. The court-appointed administrator remains in place while the mismanagement inquiry continues, and the U.S. has shown no sign of relaxing its sanctions.

China carved out exemptions for automotive-grade parts after weeks of pressure and a growing cash-flow risk, yet the episode highlighted how quickly supply can be weaponized in both directions. For companies in adjacent segments — analog components, sensors, power modules — it seems that ownership structures now carry operational risk, even for those that don’t handle cutting-edge or strategically important tech.

This is the environment in which Nexperia will operate for the foreseeable future. The firm has the manufacturing scale and customer base to remain central to global electronics, but its position between European regulators, a Chinese parent, and U.S. export controls has narrowed the room for manoeuvre.

The question is whether a long-term governance structure can emerge that satisfies all three camps while preserving the continuity that its customers depend on. Until that happens, the full implications of the 2025 intervention will continue to reverberate across one of the most fundamental layers of the semiconductor supply chain.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.