Nvidia’s TiDAR experiment could speed up AI token generation using hybrid diffusion decoder — new research boasts big throughput gains, but limitations remain

A new Nvidia research paper outlines a hybrid diffusion–autoregressive decoder that delivers major throughput gains at a small scale.

As the AI race between companies, nations, and ideologies continues apace, Nvidia has released a paper describing TiDAR, a decoding method that merges two historically separate approaches to accelerating language model inference. Language models produce text one token at a time, where a token is a small chunk of text, such as a word fragment or punctuation mark.

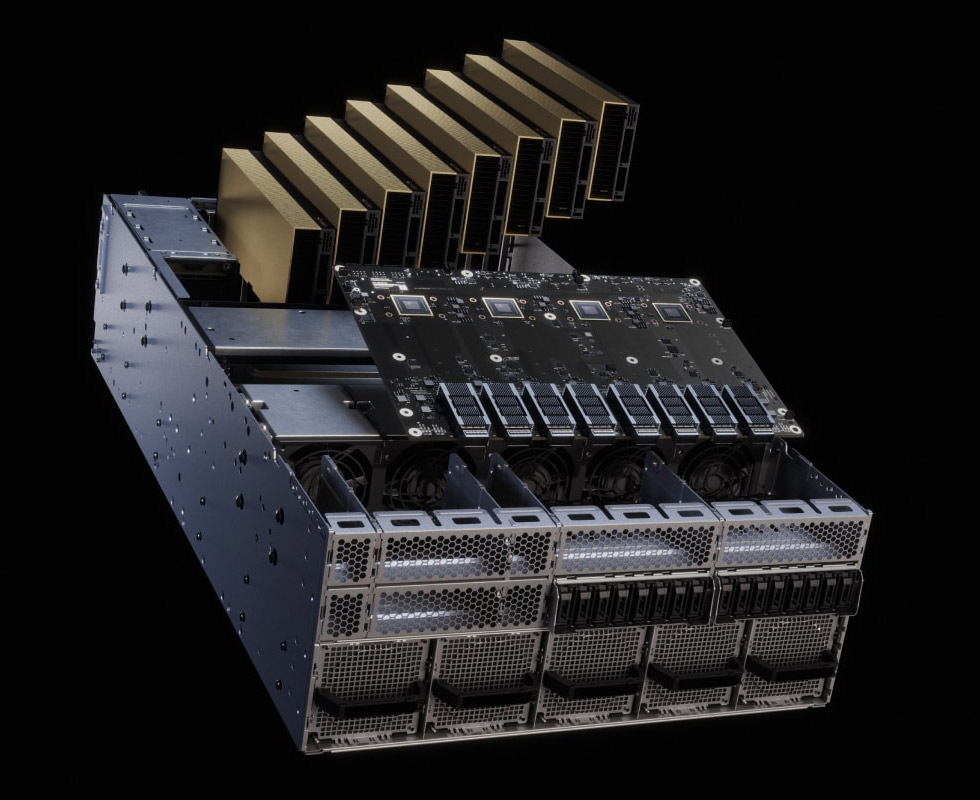

Each token normally requires a full forward pass through the model, and that cost dominates the speed and expense of running today’s AI systems. If a model can safely produce several tokens per step without losing quality, it could lead to faster response times, lower GPU hours, and reduced operating costs per request, all of which could add up to substantial savings for operators running large AI deployments, running the latest Nvidia hardware.

The TiDAR study focuses on batch-one decoding and reports between four and six times higher token throughput than the Qwen2.5 and Qwen3 baselines used for comparison. The researchers evaluate 1.5 billion and 8 billion parameter models and show that speed gains can be achieved without measurable degradation on coding and math benchmarks. Although the work sits firmly in the research stage, it demonstrates why a GPU processing a single sequence can often compute more than one token’s worth of work per step without paying extra latency.

The paper joins a wave of research that attempts to exploit the imbalance between memory movement and computation during autoregressive decoding. On an H100, next-token generation is typically limited by the cost of loading model weights and KV cache from High Bandwidth Memory (HBM). Nvidia highlights this through a latency profile of Qwen3-32B: When the number of predicted token positions grows, total pass time barely shifts until the GPU becomes compute-bound.

Those unused regions of the token dimension effectively become “free slots”. TiDAR is built around the question of how much useful work a model can do inside those slots while preserving the shape of well-behaved next-token predictors.

Designed to satisfy two distributions at once

TiDAR trains a single transformer to compute both an autoregressive next-token distribution and a diffusion-style marginal distribution in parallel. This is not how diffusion language models typically work. Prior systems such as Dream, Llada, and Block Diffusion rely entirely on parallel denoising of masked blocks. The benefit is speed, but accuracy drops as block lengths grow because the model no longer maintains a strict chain factorization. TiDAR attempts to recover that structure without giving up diffusion’s parallelism.

This is achieved with a structured attention mask dividing the input into three regions. The accepted prefix behaves like any causal sequence and provides keys and values that the model caches between steps. A block of previously drafted tokens uses bidirectional attention, letting the model verify them under the autoregressive distribution. A second block filled with mask tokens awaits the diffusion predictor, which proposes several new draft candidates in parallel.

Decoding then becomes a two-stage loop. First, the diffusion head fills the masked region. On the next pass, the model checks those drafts using its autoregressive head. Accepted tokens extend the prefix. Rejected ones are handled in the same step, because the model has learned to anticipate every acceptance path from the previous round. In that same pass, the diffusion head drafts the next block. The key to the scheme is that the prefix’s causal structure ensures the KV cache remains valid, solving one of the primary deployment problems faced by earlier diffusion-based decoders.

Training continues from existing Qwen checkpoints. The authors double the sequence length by appending a fully masked copy of the original sequence and compute autoregressive and diffusion losses on the two halves. All diffusion tokens are mask tokens, which keeps the objective dense and avoids the need for complex noising schedules, and the process is applied to 1.5-billion and 8-billion parameter backbones using a 4096-token maximum context window.

Clear speed gains, but model size is a limiting factor

On HumanEval, MBPP, GSM8K, and Minerva variants, TiDAR’s accuracy matches or slightly improves upon the Qwen baselines used in training. The 1.5 billion-parameter TiDAR model averages about 7.5 generated tokens per forward pass. The 8 billion version averages just above eight. These averages turn into notable throughput gains of 4.71 times the tokens per second of Qwen2.5-1.5B for the smaller model and 5.91 times the throughput of Qwen3-8B for the larger one.

In direct comparisons with Dream, Block Diffusion, Llada, and speculative decoding based on EAGLE-3-style draft verification, TiDAR provides the best balance between speed and benchmark accuracy within the paper’s test suite.

Those results make sense given the mechanism. TiDAR performs multiple prediction tasks while the model’s weights and cached keys and values are already resident in memory, so more tokens are generated without additional memory movement. At the small scales tested, the GPU remains memory-bound rather than compute-bound across several positions, allowing the multi-token expansion to run efficiently.

Large model sizes remain untested

Ultimately, model size appears to be a limiting factor. Although the paper shows TiDAR using Qwen3-32B profiling, the method is not demonstrated with more than 8 billion parameters. The behavior of “free token slots” depends on the balance between compute density and memory bandwidth. A large model running in tensor parallel mode may saturate compute earlier in the token dimension, reducing the range in which multi-token expansions are cheap. The authors acknowledge this and mark long-context and large-scale experiments as future work.

Finally, the authors run all inference using standard PyTorch with FlexAttention on a single H100, without any custom fused kernels or low-level optimizations. This creates a fair comparison between acceleration techniques, but makes the absolute throughput figures incomplete. Systems like Medusa, EAGLE-3, and optimized speculative decoders show materially higher speeds when tuned at the kernel level. TiDAR may benefit from similar engineering, but that work remains ahead.

A method that could reshape decoding

TiDAR represents an attempt to merge the two dominant families of multi-token decoding techniques. Instead of relying on a separate draft model, as speculative decoding does, or giving up chain factorization, as diffusion-only approaches do, the authors propose a single backbone that learns both behaviours. The benefit is simplicity at inference time and a reduction in model footprint. The trade-offs appear manageable at a small scale, and the method gives a tangible demonstration of how much unused parallelism lives inside a modern GPU during next-token generation.

The “could” depends entirely on whether TiDAR scales. If its training recipe can be applied to large models without destabilizing optimization or exhausting memory budgets, it could offer a path to higher per-GPU throughput in cloud settings and lower latency for local inference on consumer GPUs. If, on the other hand, the “free slot” region shrinks once parameter counts and context windows expand, TiDAR may settle as a useful piece of research rather than a practical replacement for speculative decoding or multi-head approaches.

What the paper succeeds in showing is that autoregressive and diffusion predictors do not need to exist in separate networks. A single transformer can learn both, and it can do so without discarding the KV cache structures that make next-token generation viable at scale.

That is a meaningful contribution to inference acceleration, and the real test will come when the architecture is pushed into the size range where commercial models operate and where memory bandwidth no longer hides the cost of expanding the token dimension.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.