Qwen boss says Chinese AI models have 'less than 20%' chance of leapfrogging Western counterparts — despite China's $1 billion AI IPO week, capital can't close the gap alone

After a rush of high-profile listings in Hong Kong, Chinese AI leaders are publicly warning that funding is not closing the gap with the U.S.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

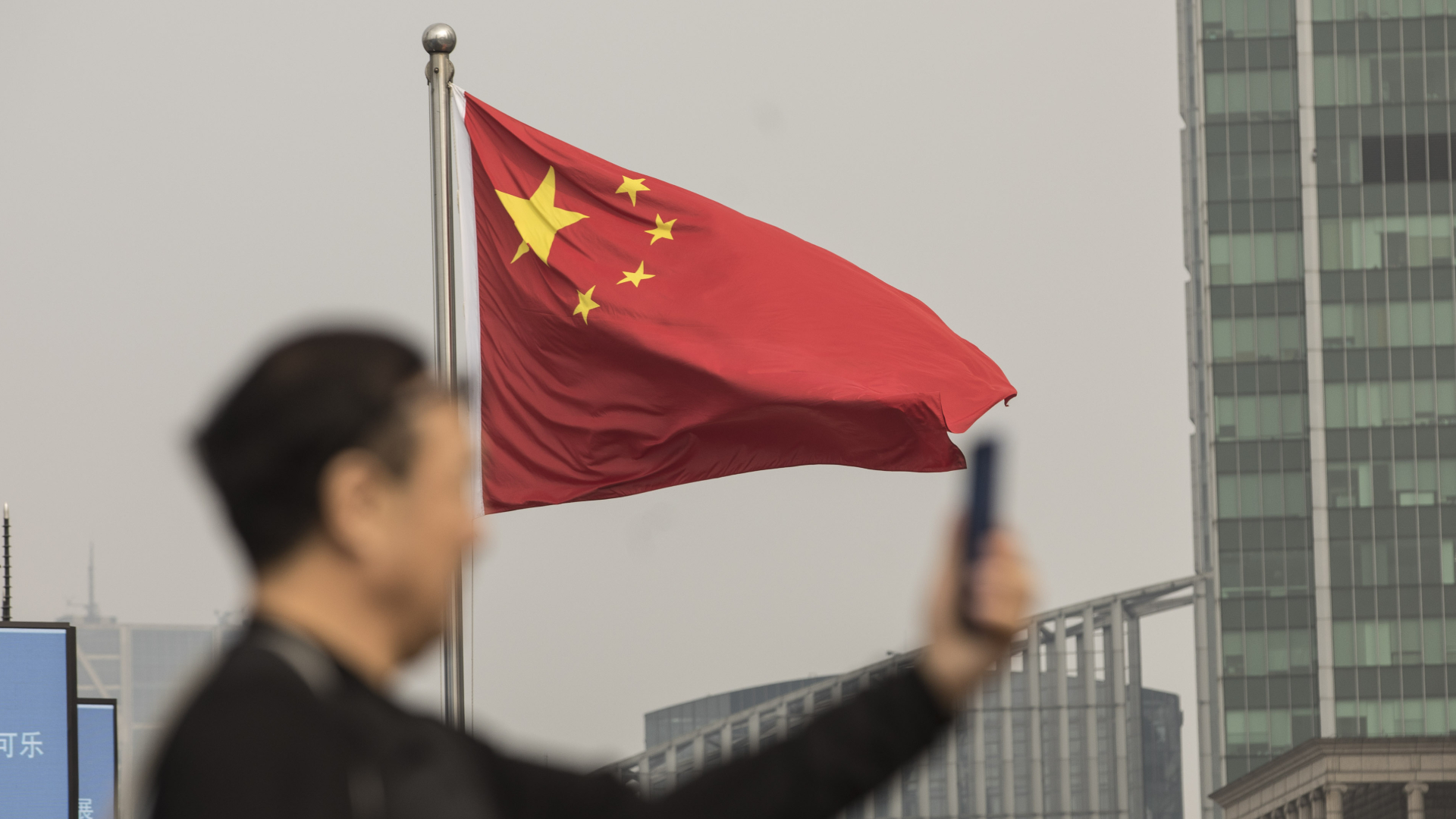

China’s AI sector made a splash this month as a cluster of domestic AI firms raised more than $1 billion through IPOs in Hong Kong. While these listings were undoubtedly meant to signal confidence, they triggered an unusually candid round of warnings from inside China’s own AI industry that the gap with the U.S. is widening in ways that fresh capital cannot easily fix.

According to reporting by Bloomberg, Justin Lin, head of Alibaba Group’s Qwen open-source models, said that Chinese companies have a “less than 20%” chance of “leapfrogging the likes of OpenAI and Anthropic with fundamental breakthroughs" in the near term.

His comments were echoed by peers at both Tencent and Zhipu AI, the latter of which is among the first Chinese foundation model companies to go public. Its IPO, along with that of Minimax, comes as Beijing is actively steering tech companies toward domestic listings, both to reduce reliance on U.S. capital markets and to funnel national savings into priority sectors like semiconductors and AI.

Companies get more runway

Getting more than $1 billion in IPOs raised in a single week is impressive for Chinese AI start-ups, a feat that would have been unthinkable even two years ago. The listings also reflect the policy shift being pushed by Chinese regulators, who are prioritizing domestic financing for AI, advanced chips, and data infrastructure. Hong Kong appears to be the preferred “offshore” venue that still offers global capital access.

For OpenAI competitor Zhipu AI, training and deploying LLMs is capital-intensive before hardware constraints even come into consideration. IPOs, therefore, offer longer funding runways than traditional venture rounds and simultaneously reduce exposure to a venture market that has cooled down massively since 2021. They also protect geopolitical swings, aligning the private sector with Beijing’s national technology priorities.

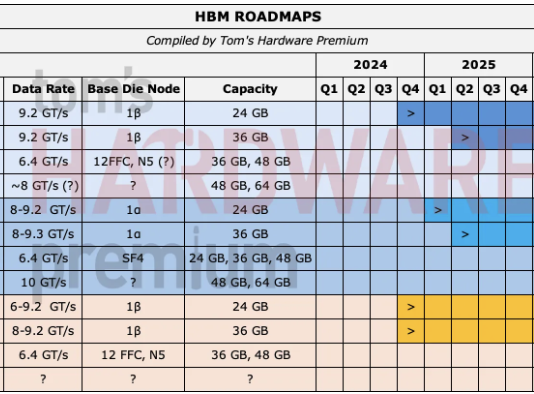

What these IPOs do not provide is leverage over the most expensive part of the AI stack. Capital might help pay for engineers and rent data centers, but it does not create advanced GPUs or high-bandwidth memory (HBM). Following the IPOs and easing of funding pressure, several executives now fear that China's biggest bottleneck is now decisively on compute availability and power.

“A massive amount of OpenAI’s compute is dedicated to next-generation research, whereas we are stretched thin — just meeting delivery demands consumes most of our resources,” Lin said at the AGI-Next summit in Beijing on Saturday, January 10.

That’s an interestingly frank admission, as it reframes how you might read into Chinese AI funding. The goal for Chinese firms isn’t to outspend U.S. hyperscalers in absolute terms, but to sustain domestic AI development under constrained conditions for as long as possible. IPOs are an endurance tool for that, rather than a shortcut to dominance, which can’t be easily bought.

Open models move fast

One area where China has made undeniable progress is open-source LLMs. Chinese labs have embraced open weights and open architectures at a scale unmatched in the U.S. Models such as Qwen, DeepSeek, and others have closed much of the performance gap on standardized benchmarks, particularly for Chinese-language tasks and domain-specific applications.

This has clear advantages, with open models reducing duplication of effort, allowing faster iteration, and making better use of limited compute by spreading training and fine-tuning workloads across a broader ecosystem. They also align with Beijing’s preference for technology stacks that are auditable and controllable at a national level. But open models do not eliminate hardware limits, and training systems still require dense clusters of advanced accelerators, fast networking, and large pools of HBM. That’s exactly where Chinese firms are hitting a wall.

U.S. export controls have cut China off from Nvidia’s most capable data center GPUs and the advanced manufacturing tools needed to produce equivalents at scale. Domestic alternatives such as Huawei’s Ascend series have improved rapidly, but even optimistic assessments place them behind current-generation U.S. hardware in raw performance and ecosystem support. More importantly, they are produced in far smaller volumes.

As a result, Chinese AI developers face a tradeoff that their U.S. counterparts largely do not. They can train more models, or they can train larger models, but doing both simultaneously strains available infrastructure. Several firms have responded by shifting emphasis away from general-purpose foundation models toward narrower, application-specific systems that can be trained and deployed with fewer resources.

The U.S. advantage

We have been debating talent pipelines and research output when it comes to the U.S. and China for much of the past decade, but today, the differentiator is the fact that the U.S. controls the bulk of the world’s advanced AI compute.

U.S. hyperscalers operate GPU clusters measured in the tens of thousands of accelerators, with software stacks tuned over years of production use. Private investment in U.S. AI companies continues to dwarf that in China, even as Chinese firms turn to public markets. Just as important, U.S. companies can deploy capital directly into hardware procurement at a global scale, something Chinese firms cannot match under current geopolitical dynamics.

Chinese execs have begun acknowledging this imbalance publicly, warning that U.S. AI infrastructure may be an order of magnitude larger than China’s in effective capacity. That gap compounds over time and, unfortunately for China, more compute enables larger models, which attract more users, data, and revenue, which in turn fund even larger deployments.

So, while a $1 billion IPO week is impressive on the face of it, it still leaves China well behind the U.S. in all the areas that matter. Yes, it ensures that China’s AI firms remain viable and competitive domestically, but it does not, in its own right, alter the global AI race.

Public listings also impose discipline and transparency, in theory, and lock firms more tightly into national industrial policy. Over the next few years, that’s likely to produce a bifurcated outcome, with China’s AI ecosystem advancing quickly in areas where scale isn’t quite so important, such as consumer and industrial platforms and applied AI.

Meanwhile, the cutting edge of general-purpose AI remains anchored in environments that have access to abundant compute. Capital can sustain progress, sure, but compute ultimately determines whether that progress will have any measurable impact outside of China.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.