The Nvidia H200 export saga, as it happened — Beijing ponders response and buyers line up, while Blackwell remains locked behind restrictions

Washington reopens path for Nvidia’s H200 after yearlong ban

The U.S. government has formally approved the export of Nvidia’s high-performance H200 AI chips to China, reinstating access to a class of silicon previously barred under national security rules. Sales will be allowed to select Chinese customers pending government review, and each chip must be routed through U.S. territory for inspection and accompanied by a 25% import duty. The move ends a freeze that ultimately led to Nvidia losing its entire Chinese market share and upended development plans for large-scale AI models in the region.

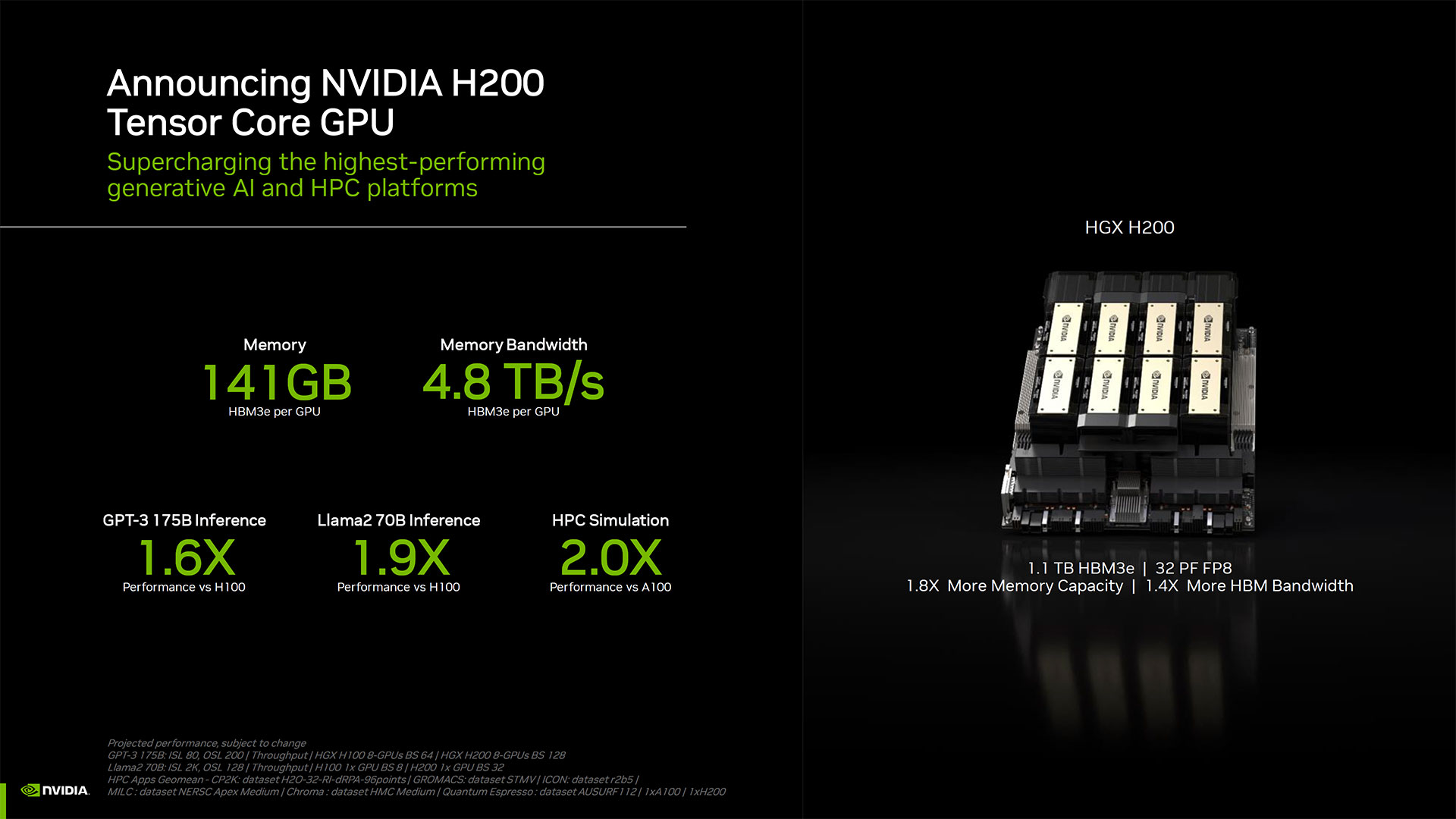

The announcement, first made by President Donald Trump via Truth Social, comes after months of internal debate within the U.S. administration over how to apply export restrictions without accelerating China’s ability to develop domestic alternatives. The H200, a powerful GPU from Nvidia’s Hopper generation, significantly outperforms the previously approved H20 and had been considered too capable for Chinese markets under earlier rules. Its reauthorization hints that there’s been a shift in Washington’s approach, namely to maintain technological superiority, but it will allow controlled access to limit the pace of Chinese self-sufficiency.

An unexpected U-turn

The decision to allow H200 exports follows concerns that sweeping restrictions were producing unintended results. Since the initial wave of AI chip bans in 2022, Chinese firms have intensified development of homegrown accelerators, with Huawei’s Ascend 910C making significant progress in training and inference workloads. While still behind Nvidia in absolute performance, Huawei’s architecture is increasingly seen as serviceable for national and commercial deployments, especially as its fabrication partners improve yields.

Internal discussions in Washington, as reported by multiple sources, shifted focus from outright denial to managed access. Officials seem to have eventually concluded that permitting H200 sales — while keeping newer architectures like Blackwell and the upcoming Rubin out of reach — could slow China’s push for chip independence without giving away the U.S. lead in performance. The H200 remains one generation behind Nvidia’s cutting-edge designs but is fully capable of training modern foundation models and large-scale AI systems.

This repositioning allows U.S. regulators to reassert some control over China's access to advanced silicon while capturing financial and political value from every sale. Under the terms of the new export framework, each H200 must be manufactured by TSMC, shipped to the U.S. for inspection, and then re-exported to China. The 25% duty is collected at the U.S. checkpoint, with the funds directed to federal revenue.

Beijing convenes tech firms and weighs conditions

Chinese regulators have not publicly responded to the U.S. announcement but are said to have begun internal reviews. According to reporting by The Information, officials from the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology have held meetings with Alibaba, ByteDance, and Tencent to assess their projected demand for H200 GPUs. The companies have been asked to provide use cases and expected unit volumes, with the understanding that the government may impose caps or usage guidelines.

Two sources present at those meetings told The Information that regulators are considering import limits tied to domestic procurement. Companies may be required to demonstrate that they are also investing in Chinese accelerators such as Huawei’s Ascend or Cambricon’s Siyuan series. This model, used previously to guide purchases of data center components and server platforms, allows Beijing to balance near-term hardware needs with its goal of reducing reliance on U.S. suppliers.

China has also continued to apply informal pressure to shift buyers toward domestic chips. In August, Chinese regulators issued guidance to steer state-backed entities and infrastructure projects away from Nvidia’s H20, resulting in widespread cancellations of contracts. The H200 presents a different scenario, given its substantial performance advantage, but officials are expected to apply similar discretion in determining which sectors and use cases are eligible.

SuperCloud, a domestic cloud services provider, confirmed that it expects major Chinese companies to proceed with H200 purchases if permitted, though in a subdued fashion. “The training of leading Chinese AI models still relies on Nvidia cards,” said Zhang Yuchun, a general manager at SuperCloud, when speaking to Reuters. “I expect the leading Chinese tech companies to buy a lot although in a low key manner.”

Production limits may slow short-term access

Nvidia’s ability to meet demand in China will likely be constrained by supply. The company has kept H200 output relatively low as it focused on ramping production of its Blackwell-class B100 and B200 GPUs, as well as preparing for its Rubin successor. Also speaking to Reuters, two sources familiar with Nvidia’s supply chain said that H200 manufacturing has been deprioritized in favor of fulfilling high-margin orders from U.S. hyperscalers and sovereign AI programs in allied countries.

Chinese firms looking to place orders may therefore find themselves at the back of the queue. Alibaba and ByteDance are both thought to be “keen to place large orders” should Chinese regulators give them the green light to do so. However, the companies are concerned about supply and are said to be actively seeking clarity from Nvidia on this.

If all this goes ahead, the H200 would reintroduce training-scale compute capacity to Chinese AI developers after a long period of reliance on repurposed hardware and grey-market acquisitions. The chip delivers roughly six times the performance of the H20 and approaches the capabilities of Nvidia’s H100, which has been banned from China since late 2022. Unlike most Chinese accelerators, the H200 supports Nvidia’s CUDA software ecosystem, simplifying model porting and cluster integration.

Ultimately, Nvidia is unlikely to resume large-scale H200 production unless it receives strong approval from both U.S. and Chinese regulators, and equally strong demand from Chinese customers. The chip is already considered a transitional product within Nvidia’s roadmap, with Blackwell occupying the top end of the current generation and Rubin expected to extend that lead in 2026.

Enforcement measures target diversion and smuggling

U.S. officials have attached a number of technical and procedural conditions to the H200 export approval. Each unit must be shipped to the U.S. before entering China, creating a traceable logistics trail that allows U.S. Customs and Commerce Department inspectors to verify compliance. Nvidia has also introduced optional location-verification software that can confirm whether a chip is operating in an authorized geography.

The system uses a combination of secure telemetry and latency-based network checks to determine the approximate location of a GPU within a customer’s infrastructure. While not mandatory — at least not yet — the feature has been privately demonstrated as a tool for audit and compliance. Nvidia has framed the technology as a data center management solution rather than a surveillance system, and the company has emphasized that it cannot remotely deactivate or control chips in the field.

Nonetheless, the software has raised concerns in Beijing, with the Cyberspace Administration of China questioning whether the technology constitutes a backdoor or allows external access to sensitive operations. Nvidia has stated that the system, which will first be made available on Blackwell chips, cannot be used for eavesdropping and does not transmit any user data to third parties. It remains to be seen whether Chinese buyers will enable the feature or attempt to route around it using intermediaries.

The compliance measures reflect a broader concern that export controls, while useful on paper, have proven difficult to enforce. We’ve seen several examples of banned Nvidia GPUs like the A100 and H100 appearing in the likes of Chinese university research and start-up product documentation since their respective bans. Many of these were likely acquired through grey-market channels or indirect resellers in third countries.

The U.S. Justice Department has already indicted several individuals involved in smuggling high-performance Nvidia chips to China in violation of export rules. Cases are ongoing in multiple districts, and officials have signaled that enforcement will intensify as more tracking capabilities become available.

A concession?

The approval of H200 exports arguably represents a concession rather than any long-term structural change in U.S. policy. The Biden and Trump administrations have consistently maintained that the U.S. must retain leadership in AI hardware and semiconductor manufacturing. The H200, while advanced, is no longer Nvidia’s leading product, and allowing access to it gives Washington a tool to slow China’s push for independence without giving up the top tier of its technology stack.

From Beijing’s perspective, the decision provides short-term relief. AI developers can resume training at scale using supported hardware and familiar toolchains, but the long-term imperative remains unchanged. China continues to invest in domestic foundries, chip design houses, and packaging capacity. Huawei is expanding its Ascend production targets, and other firms are attempting to design new architectures that bypass the limitations of restricted U.S. IP.

The H200 will be welcomed by those who can access it, but the approval comes with strings attached and no guarantee of duration. Chinese firms must navigate what could be a complex approvals process, limited supply, and reputational risk. Nvidia, meanwhile, must manage Washington’s expectations while preventing its technology from slipping beyond authorized use.

The success or failure of this arrangement may determine how future export rules are written. If H200 exports proceed smoothly, it could serve as a model for calibrated engagement, but if compliance breaks down or political conditions shift, the window may close just as quickly as it opened.

Luke James is a freelance writer and journalist. Although his background is in legal, he has a personal interest in all things tech, especially hardware and microelectronics, and anything regulatory.