Industry preps new 'cheap' HBM4 memory spec with narrow interface, but it isn't a GDDR killer — JEDEC's new SPHBM4 spec weds HBM4 performance and lower costs to enable higher capacity

A GDDR killer from the HBM camp? Not quite.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

JEDEC, the organization responsible for defining the specifications of industry-standard memory types, is close to finalizing SPHBM4, a new memory standard designed to deliver full HBM4-class bandwidth with a 'narrow' 512-bit interface, higher capacities, and lower integration costs by leveraging compatibility with conventional organic substrates. If the technology takes off, it will address many gaps in the markets HBM could serve, but as we'll explain below, it isn't likely to be a GDDR memory killer.

Although high-bandwidth memory (HBM) 1024-bit or 2048-bit interfaces enable unbeatable performance and energy efficiency, such interfaces take a lot of precious silicon real estate inside high-end processors, which limits the number of HBM stacks per chip and therefore memory capacity supported by AI accelerators, impacting both the performance of individual accelerators as well as the capabilities of large clusters that use them.

HBM in a 'standard' package

The Standard Package High Bandwidth Memory (SPHBM4) addresses this issue by reducing the HBM4 memory interface width from 2048 bits to 512 bits with 4:1 serialization to maintain the same bandwidth. JEDEC doesn't specify whether '4:1 serialization' means quadrupling the data transfer rate from 8 GT/s in HBM4, or introducing a new encoding scheme with higher clocks. Still, the goal is obvious: preserve aggregate HBM4 bandwidth with a 512-bit interface.

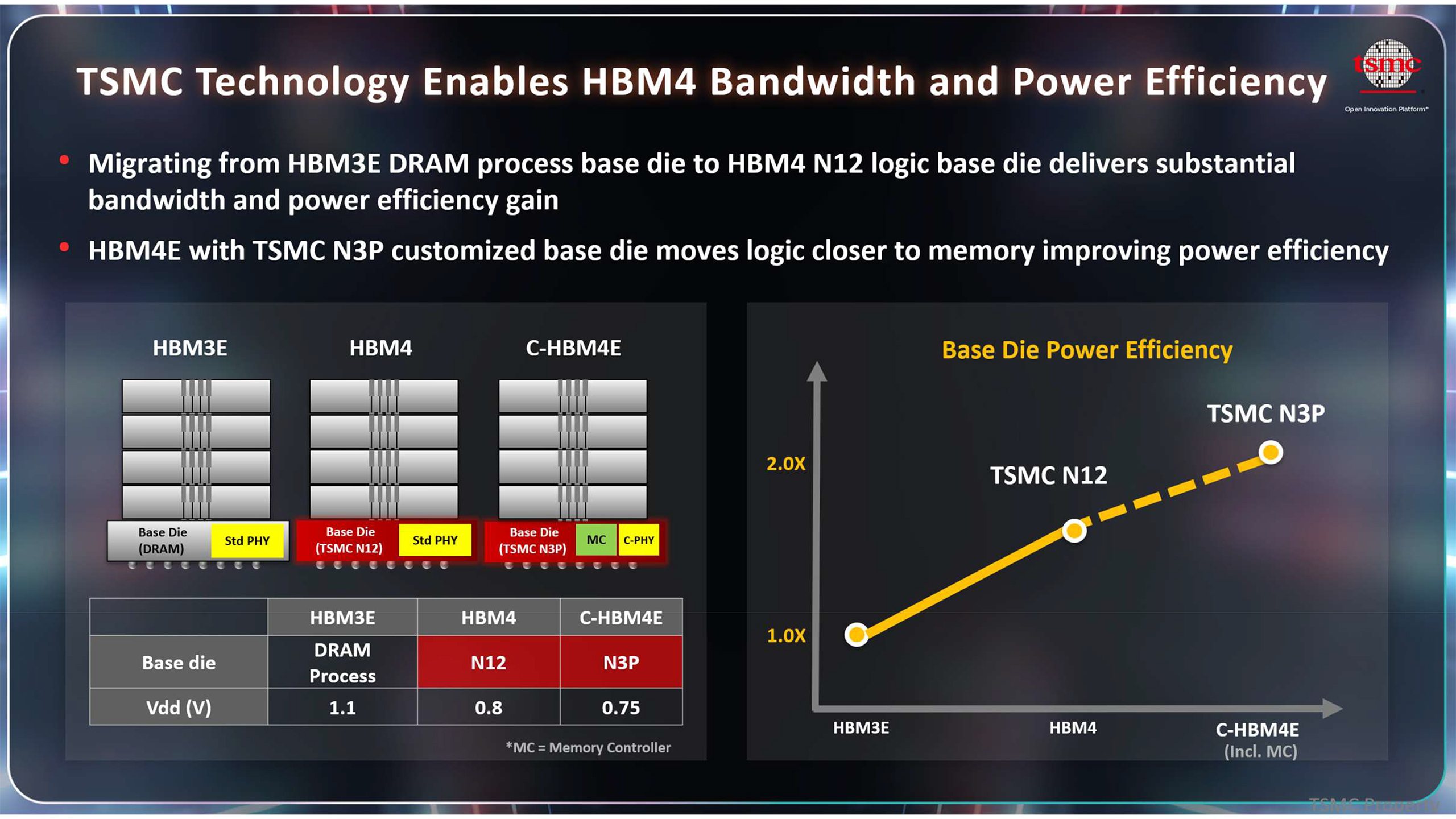

Article continues belowInside, SPHBM4 packages will use an industry-standard base die (probably made by a foundry using a logic fabrication process and therefore not cheaper as routing 'wide' DRAM ICs into a 'narrow' base die will probably get nasty here in terms of density and there will be clocking challenges due to slow wires from DRAMs and fast wires from the base die itself). It will also use standard HBM4 DRAM dies, which simplifies controller development (at least at the logical level) and ensures that capacity per stack remains on par with HBM4 and HBM4E, up to 64 GB per HBM4E stack.

On paper, this means quadrupling SPHBM4 memory capacity compared to HBM4, but in practice, AI chip developers will likely balance memory capacity with higher compute capability and the versatility they can pack into their chips, as silicon real estate becomes more expensive with each new process technology.

A GDDR7 killer?

An avid reader will likely ask why not use SPHBM4 memory with gaming GPUs and graphics cards, which could enable higher bandwidth at a moderate cost increase compared to GDDR7 or a potential GDDR7X with PAM4 encoding.

Designed to deliver HBM4-class bandwidth, SPHBM4 is fundamentally engineered to prioritize performance and capacity over other considerations, such as power and cost.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Although cheaper than HBM4 or HBM4E, SPHBM4 still requires stacked HBM DRAM dies that are physically larger and therefore more expensive than commodity DRAM ICs, an interface base die, TSV processing, known-good-die flows, and advanced in-package assembly. These steps dominate cost and scale poorly with volume compared to commodity GDDR7, which benefits from enormous consumer and gaming volumes, simple packages, and mature PCB assembly.

That said, replacing many GDDR7 chips with a single advanced SPHBM4 may not reduce costs; it may increase them.

The art is in the implementation details

While a 512-bit memory bus remains a complex interface, JEDEC says SPHBM4 enables 2.5D integration on conventional organic substrates and does not require expensive interposers, significantly lowering integration costs and potentially expanding design flexibility. Meanwhile, with an industry-standard 512-bit interface, SPHBM4 can offer lower costs (thanks to the volume enabled by standardization) compared to C-HBM4E solutions that rely on UCIe or proprietary interfaces.

Compared to silicon-based solutions, organic substrate routing enables longer electrical channel lengths between the SoC and the memory stacks, potentially easing layout constraints in large packages and accommodating more memory capacity near the package than is currently possible. Still, it is hard to imagine routing of a 3084-bit memory interface (alongside data and power wires) using conventional substrates, but we'll see about that.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our latest news, analysis, & reviews in your feeds.

Anton Shilov is a contributing writer at Tom’s Hardware. Over the past couple of decades, he has covered everything from CPUs and GPUs to supercomputers and from modern process technologies and latest fab tools to high-tech industry trends.

-

usertests For consumers, we need "3D DRAM" to increase capacity, stacked DRAM won't do it cheaply.Reply

Bandwidth of GDDR7 is good enough for the most part, and rising.

GDDR does lose out on efficiency, oh well. -

teeejay94 So you literally just said it yourself it's cheaper for basically everyone if there's higher orders of HBM memory to go into GPUs and such. LMFAO. So does the current supply and demand model only apply when suppliers feel like it? Id say , yes. 100% they are cherry picking what they want to see for a lot and sell for less. Somehow higher orders of HBM memory will decrease the costs , mind bogglingly though higher orders of UDIMM ram have shot the costs through the roof. Simply amazing the mental gymnastics you gotta do to make this make sense. The truth is when something is produced on a much larger scale it costs less to produce, no matter the product, keep that in mind. It's really not hard to figure out you've been scammed and gouged by ram manufacturers. And some of you actually believe it which is the craziest part to me. Some of you actually believe it costs more to produce things on a larger scale, you get products like memory chips cheaper the more you order 💡Reply -

thestryker Reply

I don't really think higher capacity is particularly important yet until something shifts requirements wise though. CAMM2 in both LPDDR and DDR form can reach 64GB which is more than the vast majority of people need. DIMMs and SODIMMs are up to 64GB capacity per module.usertests said:For consumers, we need "3D DRAM" to increase capacity, stacked DRAM won't do it cheaply.

At this point I'm kind of hoping that all the focus on enterprise sales will mean as things normalize we'll see more high capacity kits at reasonable prices. Also hoping that memory IC built on newer manufacturing processes will scale better bandwidth/latency/capacity wise. We've seen a little bit of that with 32Gb IC, but most of those kits have just been announced rather than hitting the market. -

usertests Reply

We're looking at up to 10 years before it hits market. The most obvious consumer/prosumer application of higher capacities would be larger local LLMs, in the 100 billion to 1 trillion parameter range. Outside of purely text, I think some of the video generation models can already use over 50 GB of memory.thestryker said:I don't really think higher capacity is particularly important yet until something shifts requirements wise though. CAMM2 in both LPDDR and DDR form can reach 64GB which is more than the vast majority of people need. DIMMs and SODIMMs are up to 64GB capacity per module.

Simply increasing capacity while lowering the cost should open up new non-AI applications though. I think we feel that we have more than enough because DRAM scaling slowed down so much over the last 15 years, that it couldn't be "wasted" at the same rates anymore.