Exploring Clawdbot, the AI agent taking the internet by storm — AI agent can automate tasks for you, but there are significant risks involved

The new pseudo-locally-hosted gateway for agentic AI offers a sneak peek at the future—both good and bad.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you've spent any time in AI-curious corners of the internet over the past few weeks, you've probably seen the name "Clawdbot" pop up. The open-source project has seen a sudden surge in attention, helped along by recent demo videos, social media chatter, and the general sense that "AI agents" are the next big thing after chatbots. For folks encountering it for the first time, the obvious questions follow quickly: What exactly is Clawdbot? What does it do that ChatGPT or Claude don't? And is this actually the future of personal computing, or a glimpse of a future we should approach with caution?

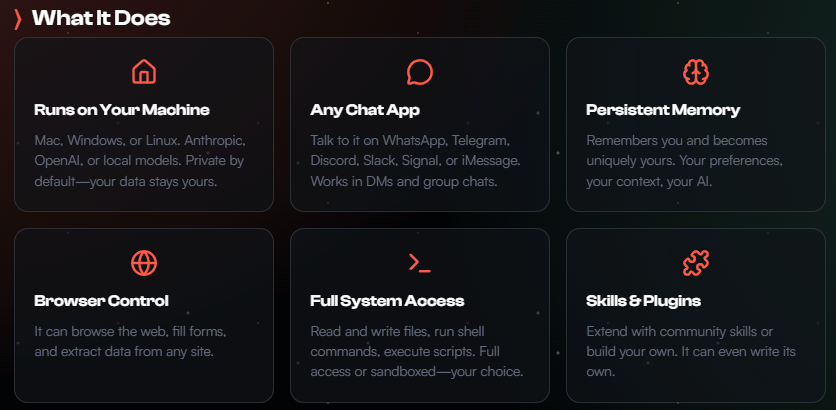

The developers of Clawdbot position it as a personal AI assistant that you run yourself, on your own hardware. Unlike chatbots accessed through a web interface, Clawdbot connects to messaging platforms like Telegram, Slack, Discord, Signal, or WhatsApp, and acts as an intermediary: you talk to it as if it were a contact, and it responds, remembers, and (crucially) acts, by sending messages, managing calendars, running scripts, scraping websites, manipulating files, or executing shell commands. That action is what places it firmly in the category of "agentic AI," a term increasingly used to describe systems that don't just answer questions, but take steps on a user's behalf.

Technically, Clawdbot is best thought of as a gateway rather than a model, as it doesn't include an AI model of its own. Instead, it routes messages to a large language model (LLM), interprets the responses, and uses them to decide which tools to invoke. The system runs persistently, maintains long-term memory, and exposes a web-based control interface where users configure integrations, credentials, and permissions.

From a user perspective, the appeal is obvious. You can ask Clawdbot to summarize conversations across platforms, schedule meetings, monitor prices, deploy code, clean up an inbox, or run maintenance tasks on a server, for example, all through natural language. It's the old "digital assistant" promise, but taken more seriously than voice-controlled reminders ever were. In that sense, Clawdbot is less like Apple's Siri and more like a junior sysadmin who never sleeps, at least theoretically.

Not exactly as "local" as often advertised by fans

We should clarify one important detail obscured by the hype, though: by default, Clawdbot does not run its AI locally, and doing so is non-trivial. Most users connect it to cloud-hosted LLM APIs from providers like OpenAI, or indeed, Anthropic's "Claude" series of models, which is where the name comes from.

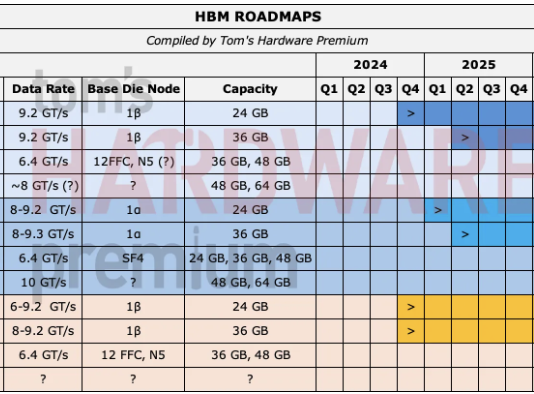

Running a local model is possible, but doing so at a level that even approaches cloud-hosted frontier models requires substantial hardware investment in the form of powerful GPUs, plenty of memory, and a tolerance for tradeoffs in speed and quality. For most users, "self-hosted" refers to the agent infrastructure, not the intelligence itself. Messages, context, and instructions still pass through external AI services unless the user goes out of their way to avoid that.

This architectural choice matters because it shapes both the benefits and the risks. Clawdbot is powerful precisely because it concentrates access. It has all of your credentials for every service it touches because it needs them. It reads all of your messages because that's the job. It can run commands because otherwise it couldn't automate anything. In security terms, it becomes an extremely high-value target; a single system that, if compromised, exposes a user's entire digital life.

That risk was illustrated recently by security researcher Jamieson O'Reilly, who documented how misconfigured Clawdbot deployments had left their administrative interfaces exposed to the public internet. In hundreds of cases, unauthenticated access allowed outsiders to view configuration data, extract API keys, read months of private conversation history, impersonate users on messaging platforms, and even execute arbitrary commands on the host system, sometimes with root access. The specific flaw O'Reilly identified, a reverse-proxy configuration issue that caused all traffic to be treated as trusted, has since been patched.

Focusing on the patch misses the point, though. The incident wasn’t notable because it involved a clever exploit; it was notable because it exposed the structural risks inherent in agentic systems. Even when correctly configured, tools like Clawdbot require sweeping access to function at all. They must store credentials for multiple services, read and write private communications, maintain long-term conversational memory, and execute commands autonomously.

This can technically still conform to the principle of least privilege, but only in the narrowest sense; the "least" privilege an agent needs to be useful is still an extraordinary amount of privilege, concentrated in a single always-on system. Fixing one misconfiguration doesn’t meaningfully reduce the blast radius if another failure occurs later, and experience suggests that eventually, something always does.

Agentic AI is awfully convenient, but great caution is advised

Skepticism about agentic AI is less about fear of the technology and more about basic systems thinking. Large language models are very explicitly not agents in the human sense. They don't understand intent, responsibility, or consequence. They are essentially very advanced heuristic engines that produce statistically plausible responses based on patterns, not grounded reasoning. When such systems are given the authority to send messages, run tools, and make changes in the real world, they become powerful amplifiers of both productivity and error.

It's worth noting that much of what Clawdbot does could be accomplished without an AI model in the mix at all. Regular old deterministic scripts, cron jobs, workflow engines, and other traditional automation tools can already monitor systems, move data, trigger alerts, and execute commands with far more predictability. The neural network enters the picture primarily to translate vague human language into structured actions, and that convenience is real, but it comes at the cost of opacity and uncertainty. When something goes wrong, the failure mode isn't always obvious, or even immediately visible to the user.

There is also a quieter, more practical cost to agentic AI that often gets overlooked, as many of its most ardent supporters were already paying for it, and that cost is simple: money. Most Clawdbot deployments rely on cloud-hosted AI models accessed through paid APIs, not local inference. Unlike webchat interfaces that are typically metered in the number of responses, API usage is metered by tokens. That means every message, every summary, every planning step costs something.

Agentic systems tend to be especially expensive because they are "chatty" behind the scenes, constantly maintaining context, evaluating conditions, and looping through tool calls. An always-on agent mediating multiple message streams can burn through tens or hundreds of thousands of tokens per day without doing anything particularly dramatic. Over the course of a month, that turns into a nontrivial bill, effectively transforming a personal assistant into a small but persistent operating expense.

Against this backdrop, the broader industry rhetoric starts to look a little unmoored. For example, Microsoft has openly discussed its ambition to turn Windows into an "agentic OS," where users abandon keyboards and mice in favor of voice-controlled AI agents by the end of the decade. The idea that most people will happily hand continuous operational control of their computers to probabilistic systems by 2030 deserves, at the bare minimum, a raised eyebrow. History suggests that users adopt alternative input methods and automation selectively, not wholesale, particularly when the stakes involve the loss of privacy, data, or indeed, money.

Clawdbot is a glimpse at the future

To be clear, none of this means Clawdbot is a bad project. In fact, quite to the contrary, it's a clear, well-engineered example of where agentic AI is heading, and also why people find the tech compelling. It's also neither the first nor the last tool of its kind. Similar systems are emerging across open-source communities and enterprise platforms alike, all promising to turn intent into action with minimal friction.

The more important takeaway is that tools like Clawdbot demand a level of technical understanding and operational discipline that most users simply don't have. Running your own Clawdbot requires setting up a Linux server, configuring authentication and security settings, managing permissions and a command whitelist, and a comprehensive grasp of sandboxing. Running an always-on agent with access to credentials, messaging platforms, and system commands is not the same as opening a chat window in a browser, and it never will be.

For many people, the safer choice will remain traditional cloud AI interfaces, where the blast radius of a mistake is smaller and the responsibility boundary clearer. Agentic AI may well become a foundational layer of future computing, but if Clawdbot is any indication, that future will require more caution, not less.

Zak is a freelance contributor to Tom's Hardware with decades of PC benchmarking experience who has also written for HotHardware and The Tech Report. A modern-day Renaissance man, he may not be an expert on anything, but he knows just a little about nearly everything.