Researchers turn spoiled milk into 3D printing materials — extracted proteins from dairy waste combined with polymers to create plastic alternative

This work turns what would otherwise be an agricultural liability into a potential input for advanced manufacturing.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

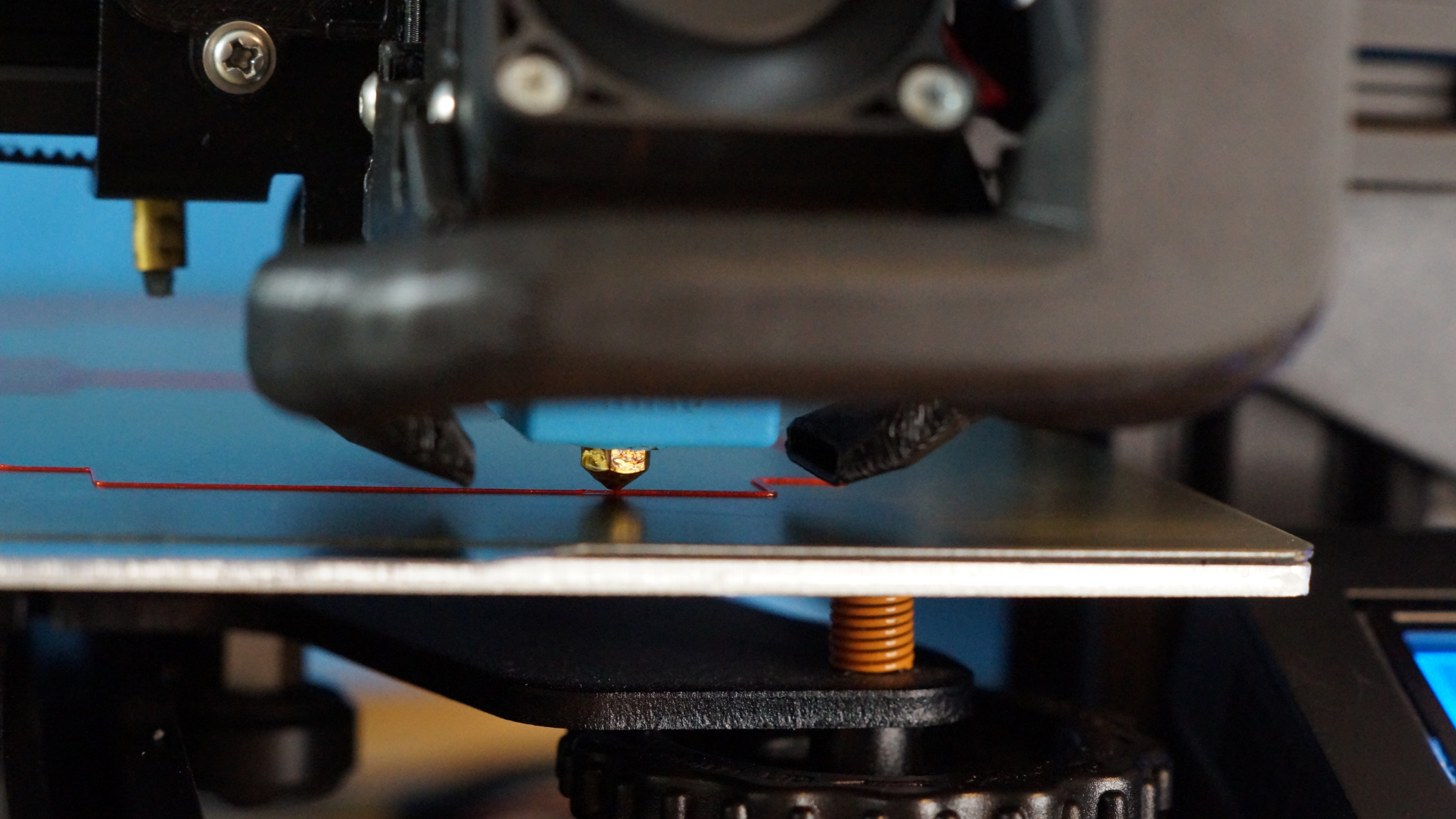

We've reported on it before, but 3D printing has a materials problem. Most filament is still petroleum-based, non-biodegradable, and destined to outlive whoever printed the cute little Benchy boat miniature. That's why a newly patented breakthrough out of the University of Wisconsin–Platteville (of course) is interesting: researchers have figured out how to turn spoiled milk into a usable bio-composite for 3D printing.

Milk printing your next phone stand might sound weird, but in a world drowning in plastic and food waste, we could use some weird ideas like this. In this case, the core idea is surprisingly elegant: milk contains proteins like casein and whey, and those proteins can be processed and blended with existing polymers to create printable materials. Instead of dumping spoiled dairy, the team developed a method to extract those proteins and repurpose them as part of a 3D printing feedstock. The result isn't "printable cheese," but rather a legitimate plastic alternative, well-suited for use in 3D printers, and derived primarily from dairy waste.

This isn't happening in a vacuum, either. Over the past few years, the 3D printing world has been quietly experimenting with ways to clean up its own mess, from grinding down failed prints and supports into recycled filament to in-home filament recyclers that let hobbyists re-extrude their plastic mistakes. There's also been growing interest in water-soluble and compostable materials, along with grassroots efforts to turn everyday waste—PET soda bottles, discarded plastic utensils, packaging scraps—into usable filament. All of these approaches chip away at the environmental footprint of additive manufacturing, even if none of them are perfect or universally practical yet.

Article continues below

What makes this notable isn't just the sustainability angle, though that's definitely a real boon. The COVID-era milk dumping crisis—where dairy farms had to dump millions of gallons of milk due to the sharp drop in demand from schools and other consumers—was the spark for the project, and this work turns what would otherwise be an agricultural liability into a potential input for advanced manufacturing. For 3D printing specifically, it points toward a future where filament isn't tied exclusively to fossil fuels without requiring a total rethink of existing printers or workflows.

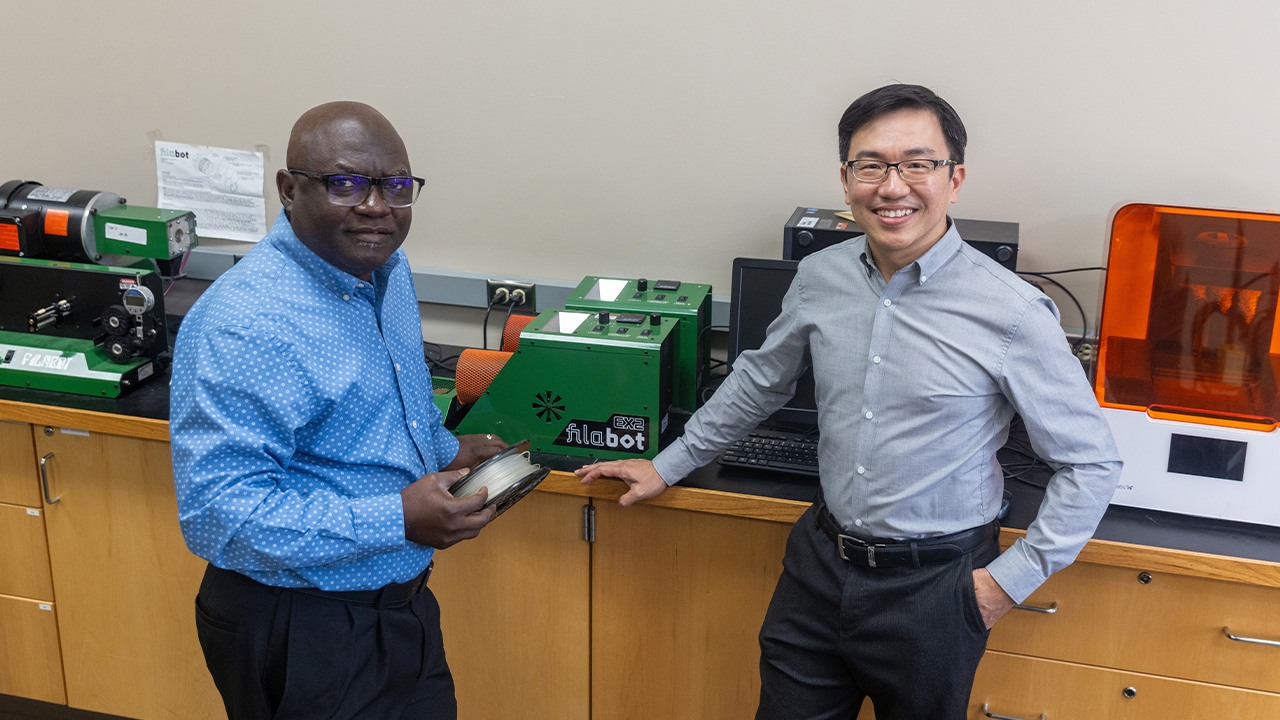

The project was led by Dr. John Obielodan, UW-Plattville's chair of the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, and Dr. Joseph Wu, Associate Professor of Chemistry. The researchers spent years dialing in protein types, purity, and blend ratios to get acceptable strength and flexibility, which is where a lot of biomaterial ideas fall apart. This wasn't a kitchen-sink experiment; it was mechanical engineering and chemistry students grinding through real materials science to make something that actually prints in existing 3D printers without excessive fouling.

If this tech gets commercialized, the implications are actually pretty big. Bio-derived filament could lower environmental impact, diversify material supply chains, and create new revenue streams for dairy producers. It's a solid example of circular economy thinking applied to additive manufacturing, resulting in less waste, fewer petrochemicals, and allowing enthusiasts and businesses to use their very same printers. It's not flashy, but it's exactly the kind of materials progress 3D printing needs to continue the move from "hobbyist toy" to mainstream manufacturing.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our latest news, analysis, & reviews in your feeds.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Zak is a freelance contributor to Tom's Hardware with decades of PC benchmarking experience who has also written for HotHardware and The Tech Report. A modern-day Renaissance man, he may not be an expert on anything, but he knows just a little about nearly everything.

-

cerata Not that surprising, as some vintage knitting needles, buttons and so on are made of casein-based bioplastic. Of course as the article points out, it's one thing to identify a possible way to repurpose waste material, but very much another to achieve the desired material properties.Reply

I'll go back to "3D-printing" some baby clothes now. -

Jame5 Replyxtracted proteins from dairy waste combined with polymers to create plastic alternative

Weirdly, if you combine most things with polymers (aka plastics) you can make plastic. -

Air2004 Reply

According to the interwebs, your statement checks out.Jame5 said:Weirdly, if you combine most things with polymers (aka plastics) you can make plastic.