Why you can trust Tom's Hardware

Comparison Products

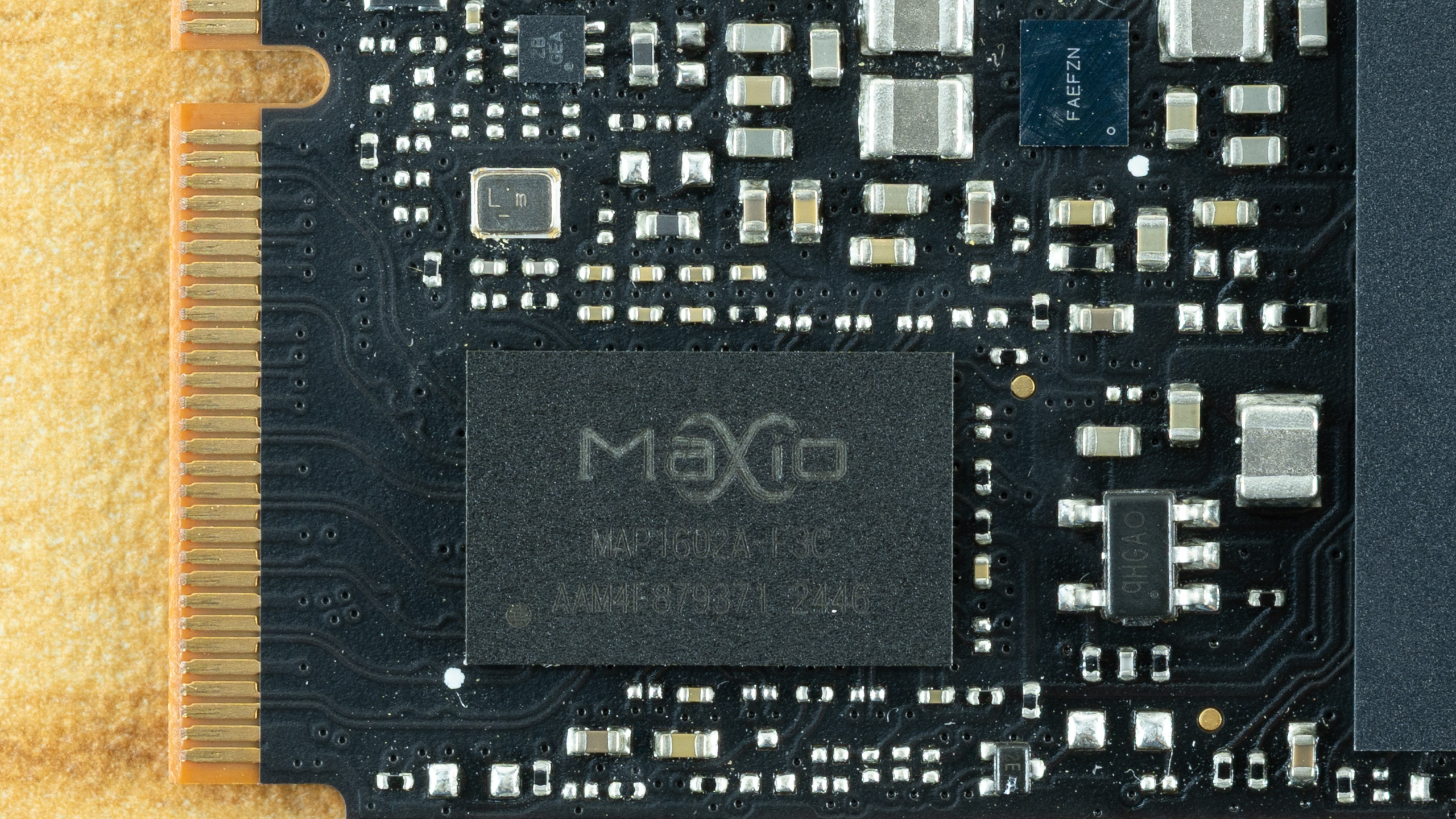

The Black Opal NV7400 is considered a budget PCIe 4.0 drive because it’s DRAM-less with only a four-channel controller, and there is a lot of competition in this space. At the top, you’re looking at drives with TLC flash – this flash is faster and has higher endurance than QLC – and specifically newer, faster TLC flash that can saturate the PCIe 4.0 link. Prominent drives here are the Lexar NM790, the TeamGroup MP44, the Sabrent Rocket 4, the SanDisk Black SN7100, which is now known as the Optimus GX 7100, and the Samsung 990 EVO Plus. The first two use the same MAP1602 controller as the NV7400. The final two use proprietary controllers instead. In the middle, the Rocket 4 is using a controller from Phison that’s comparable to the MAP1602. This covers most bases to give you a full look at the competition.

From here, we’re looking at drives with a comparable controller using QLC flash rather than TLC. In daily use, such drives can be just as fast, but you should expect to save some money, as QLC is designed to be less expensive per GB. The Acer FA200 is a good example of a drive using the same MAP1602 controller but with YMTC’s QLC flash, although of a generation equivalent to the NV7400’s TLC. Moving beyond YMTC and Micron flash, the SanDisk Blue SN5100, or now Optimus 5100, is using distinct BiCS8 QLC flash instead. This drive can punch above its weight in many benchmarks. Finally, we have the Kingston NV3, which can have TLC or QLC flash and is designed to be affordable. It’s probably the drive that will be most available universally, but its hardware is variable, meaning it can change over time.

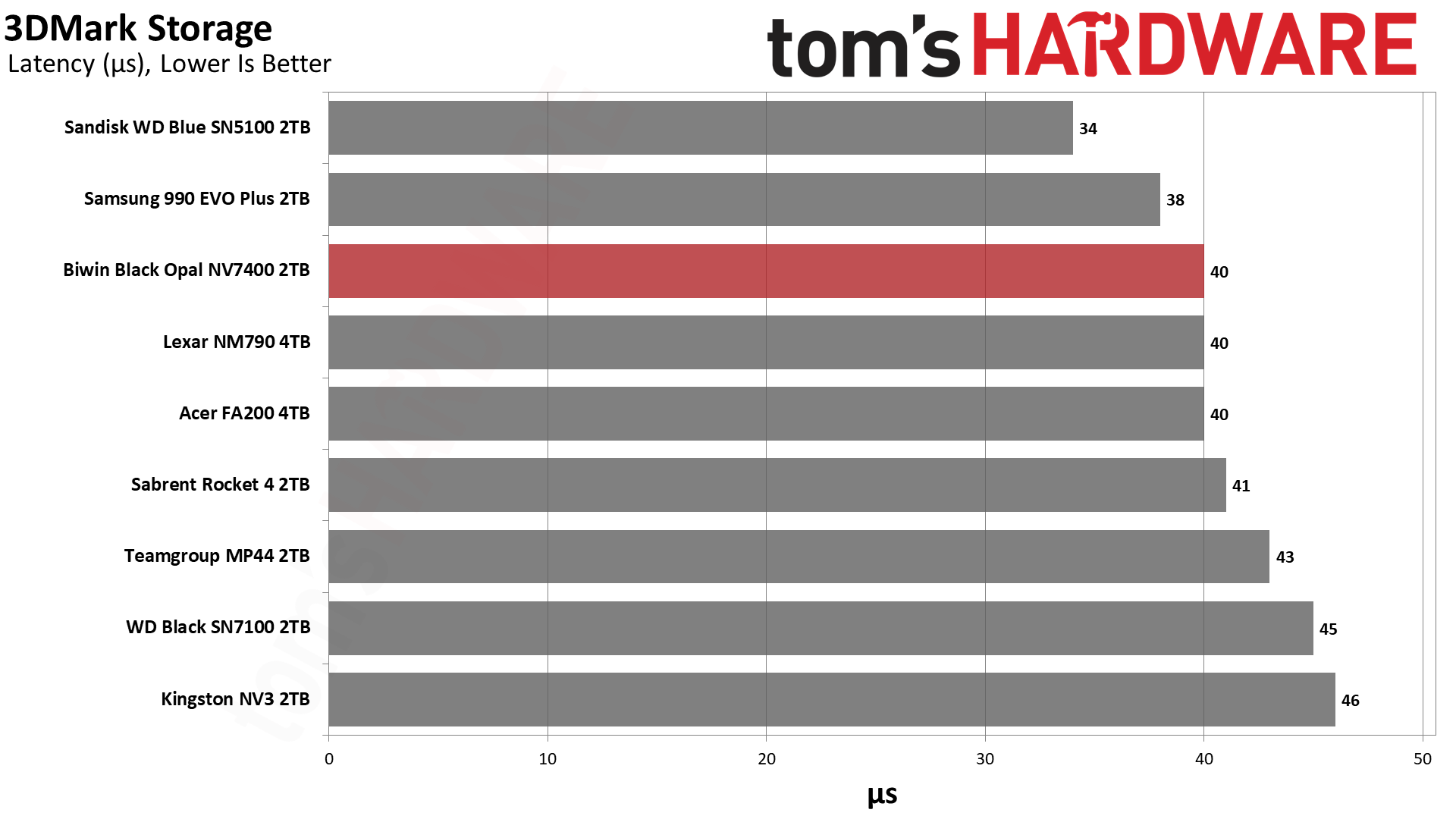

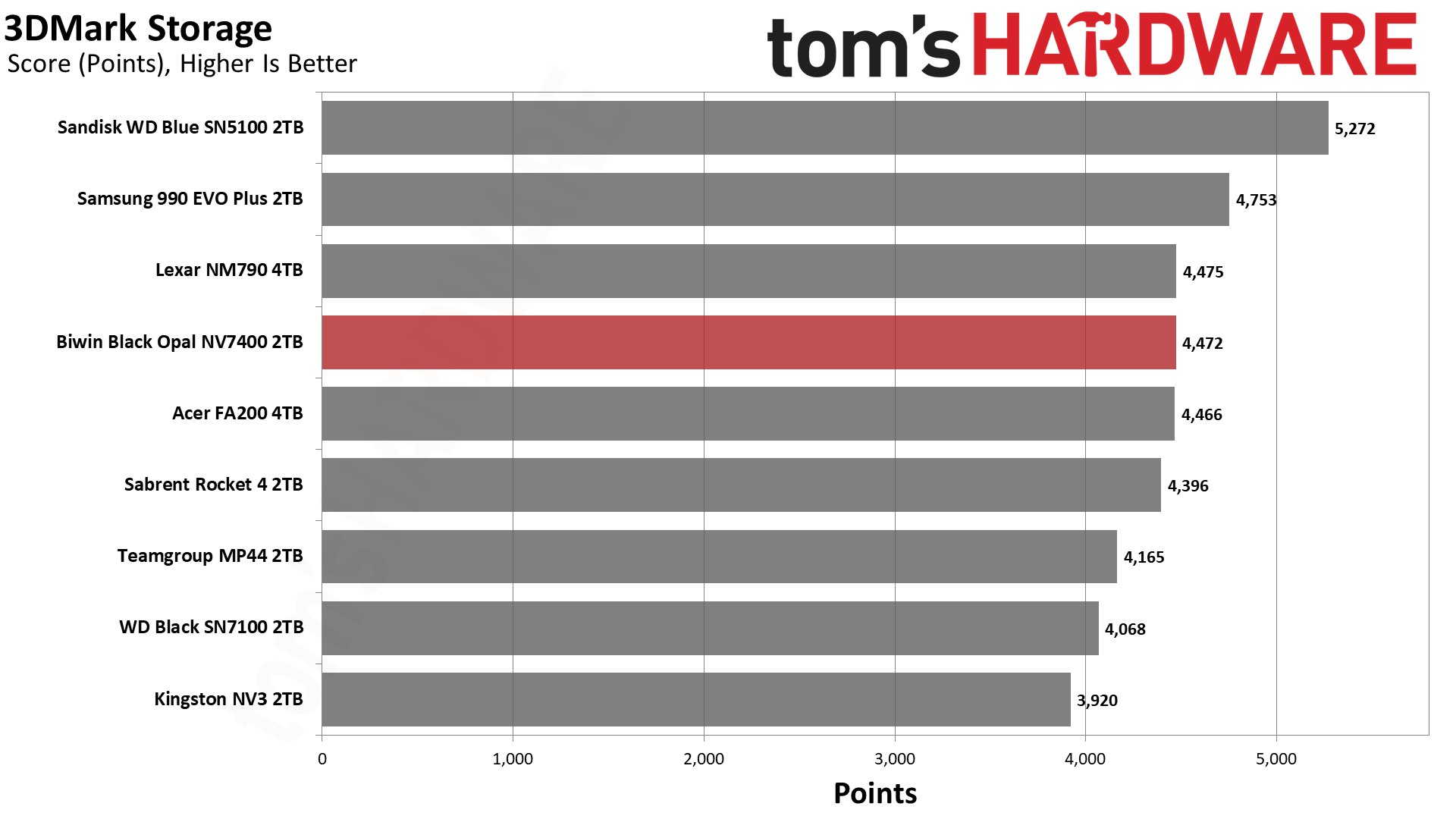

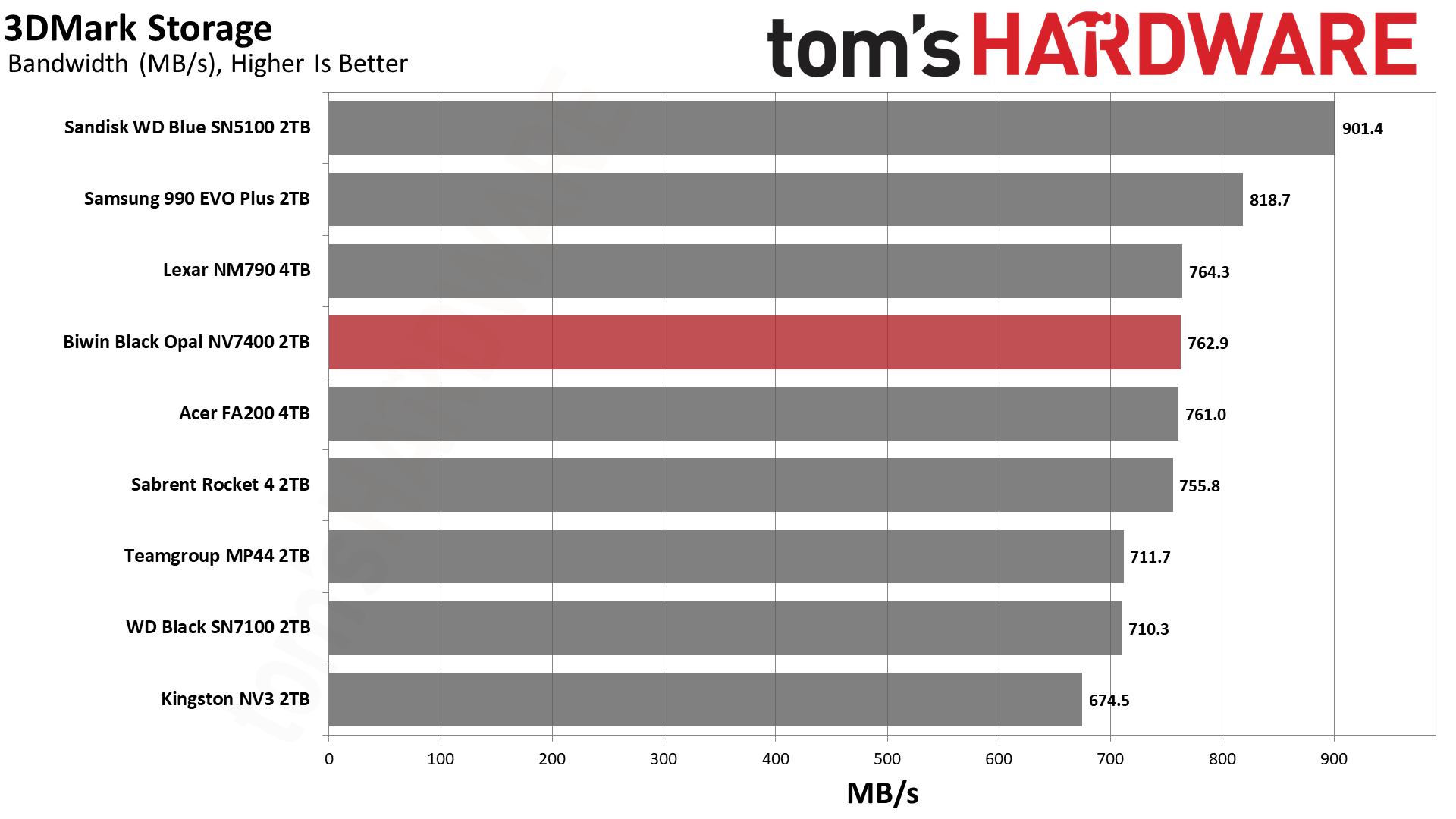

Trace Testing — 3DMark Storage Benchmark

Built for gamers, 3DMark’s Storage Benchmark focuses on real-world gaming performance. Each round in this benchmark stresses storage based on gaming activities including loading games, saving progress, installing game files, and recording gameplay video streams. Future gaming benchmarks will be DirectStorage-inclusive and we also include notes about which drives may be future-proofed.

The NV7400 delivers very good performance in 3DMark with relatively low latency, beating all but two drives. The two faster drives may surprise you – the Blue SN5100 is QLC-based, using ostensibly slower flash, and the 990 EVO Plus performs quite well considering the 990 EVO underwhelmed us in most tests. While the Blue SN5100 is not using TLC flash, the BiCS8 QLC that it does use can be very swift if it’s able to operate in the pSLC or cache mode, and QLC flash is usually optimized specifically for reads to compensate for its higher average latency.

Two drives we want to pay attention to here, in this and other tests, are the NM790 and MP44. These use the same controller as the NV7400 but with YMTC’s TLC flash instead of Micron’s. The NM790 is at a higher capacity, but Maxio has custom versions of its controller to handle more flash, so the performance impact is not severe. DRAM-less drives tend to have only half the flash channels of drives with DRAM and therefore tend to be able to handle less flash with potential performance drops at higher capacities. This isn’t the case here. That’s relevant news because 4TB drives will sometimes be the least expensive per TB, and that capacity is pretty great if you want one big drive, with the GB per $ ratio becoming more important as prices go up.

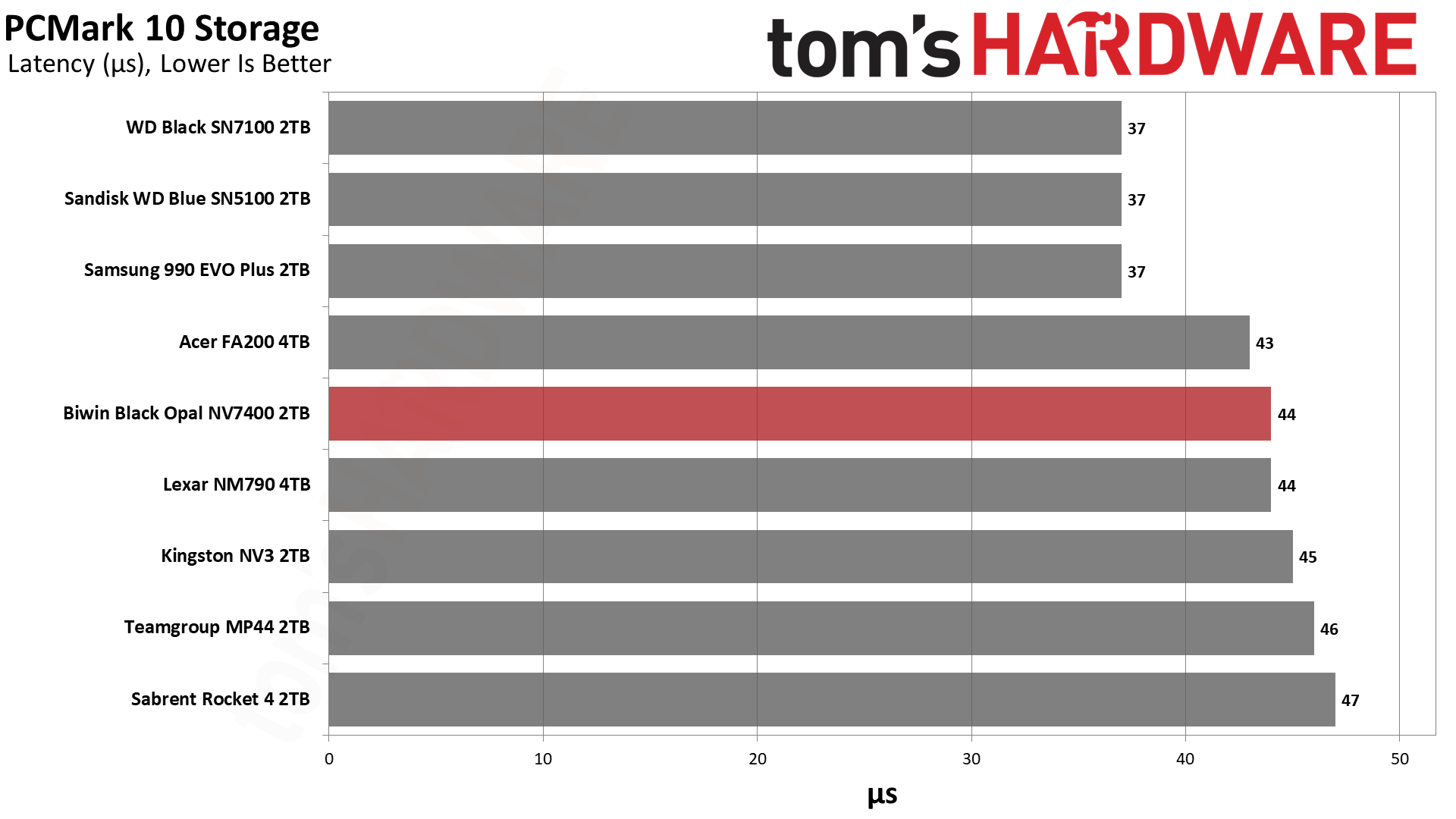

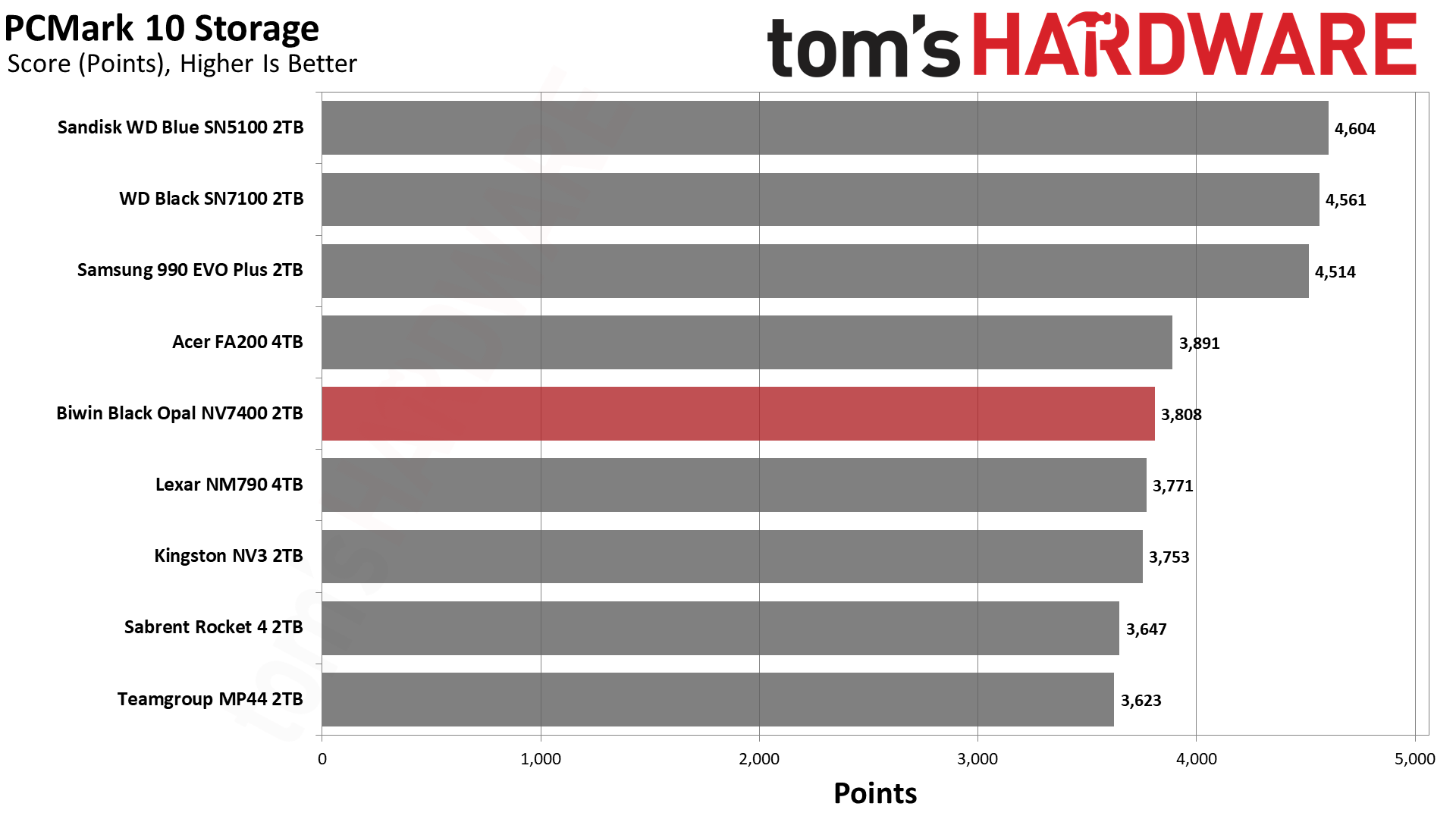

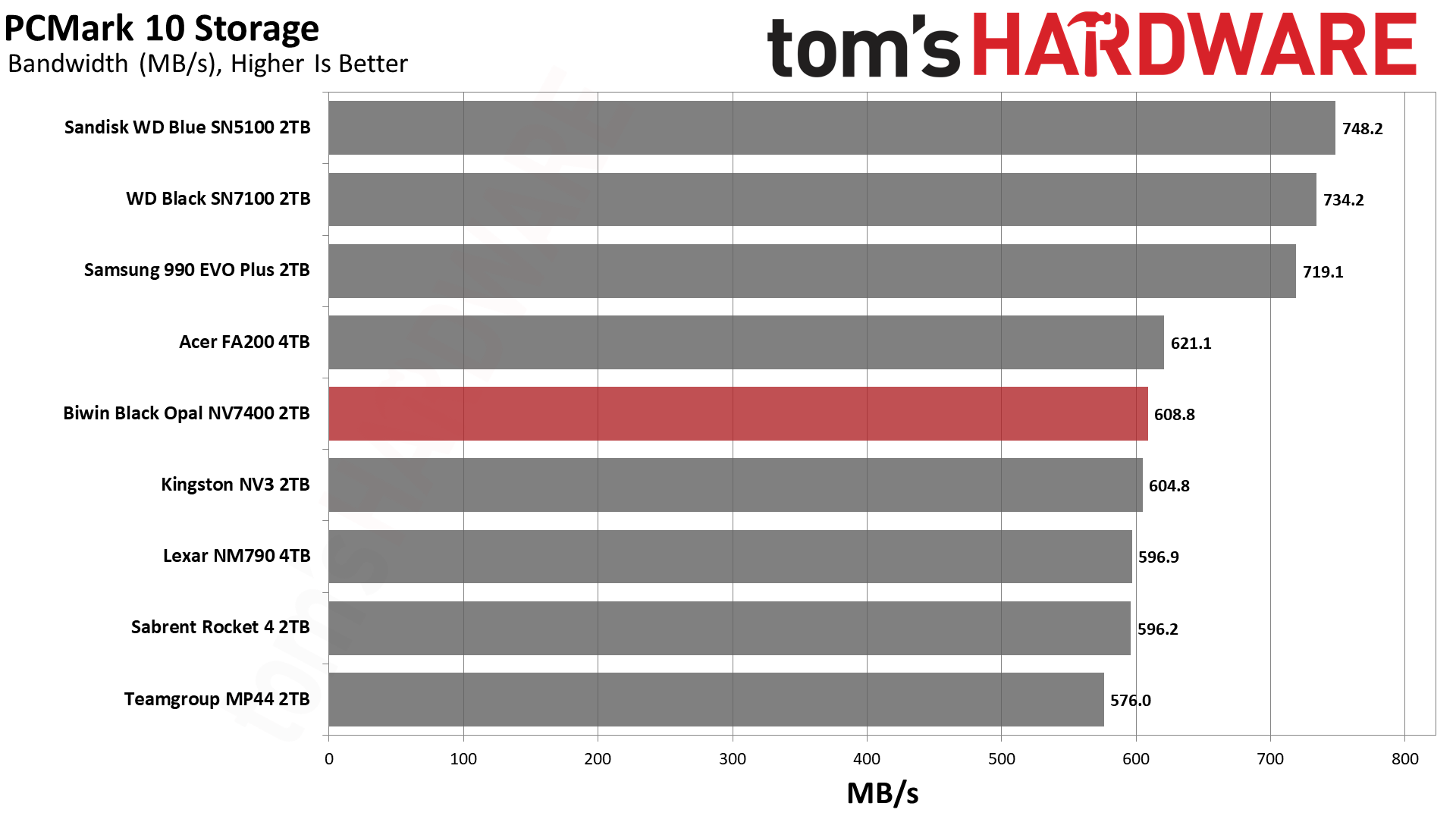

Trace Testing — PCMark 10 Storage Benchmark

PCMark 10 is a trace-based benchmark that uses a wide-ranging set of real-world traces from popular applications and everyday tasks to measure the performance of storage devices. The results are particularly useful when analyzing drives for their use as primary/boot storage devices and in work environments.

Things aren’t as rosy in PCMark 10, but the NV7400 still beats the NM790 and MP44. Things are close enough among the older drives – the Blue SN5100, Black SN7100, and 990 EVO Plus are using newer hardware – that you won’t miss out on anything by going with the NV7400. This is actually a good result because the Micron flash is holding up nicely against this scrutiny.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

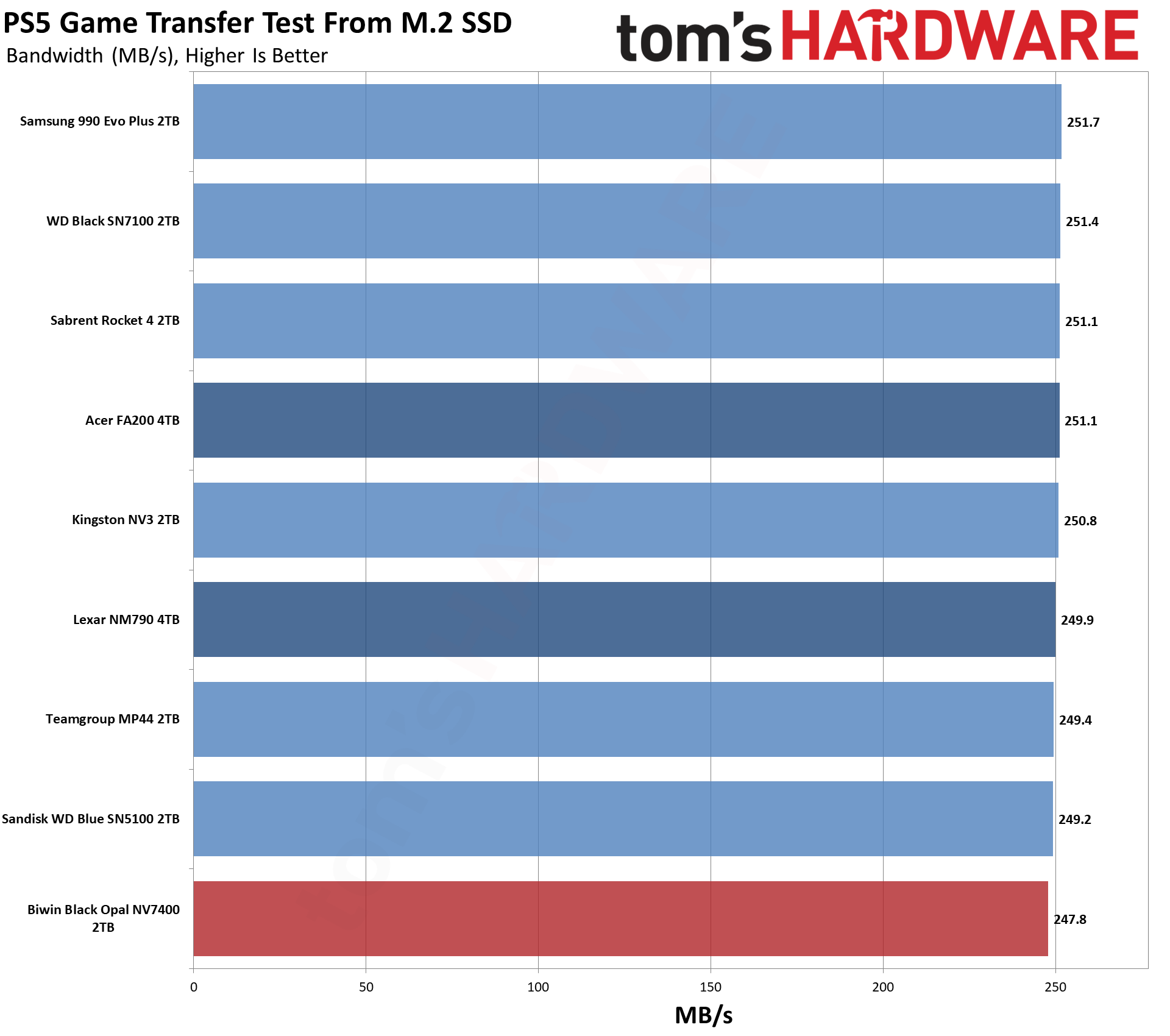

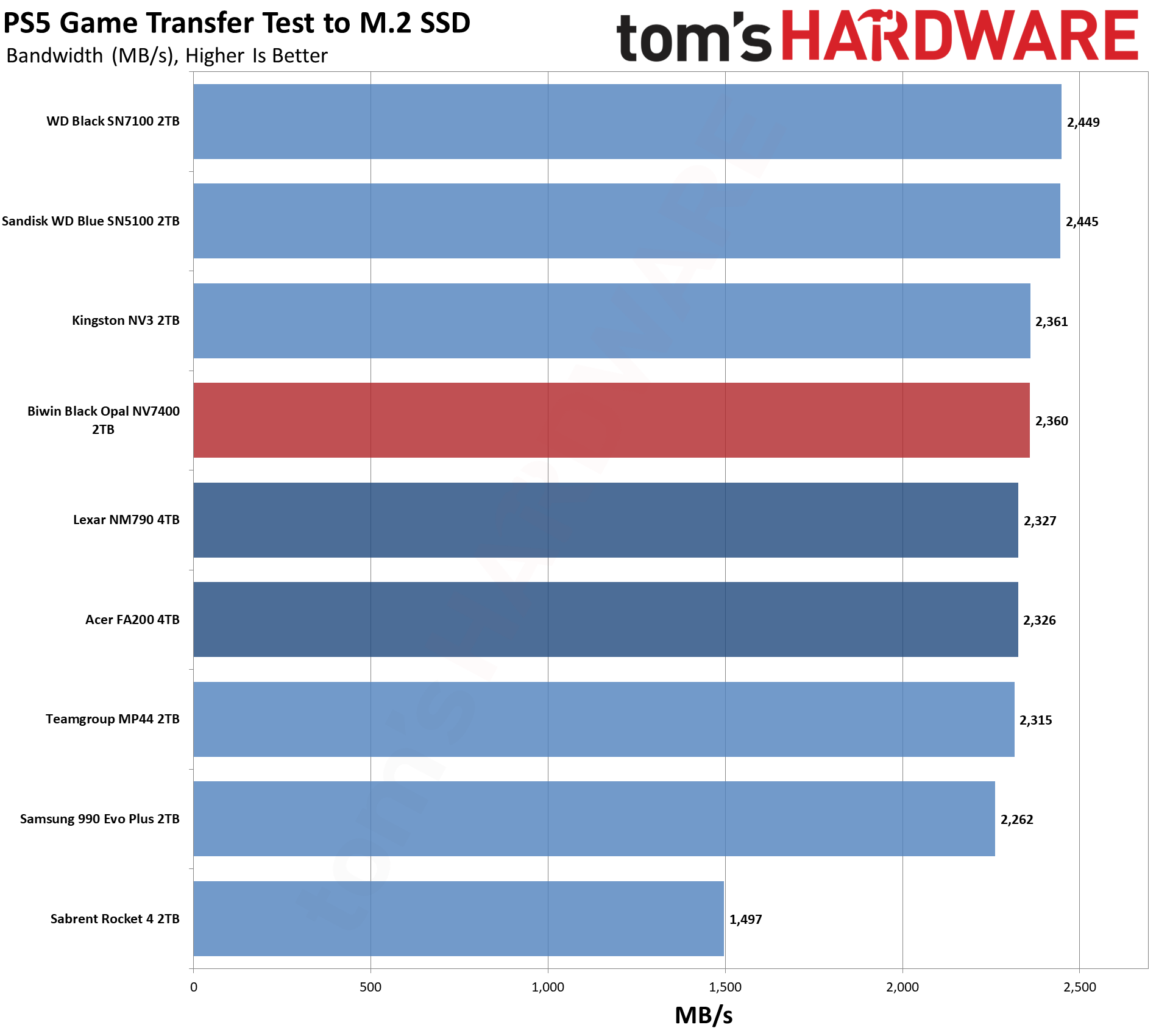

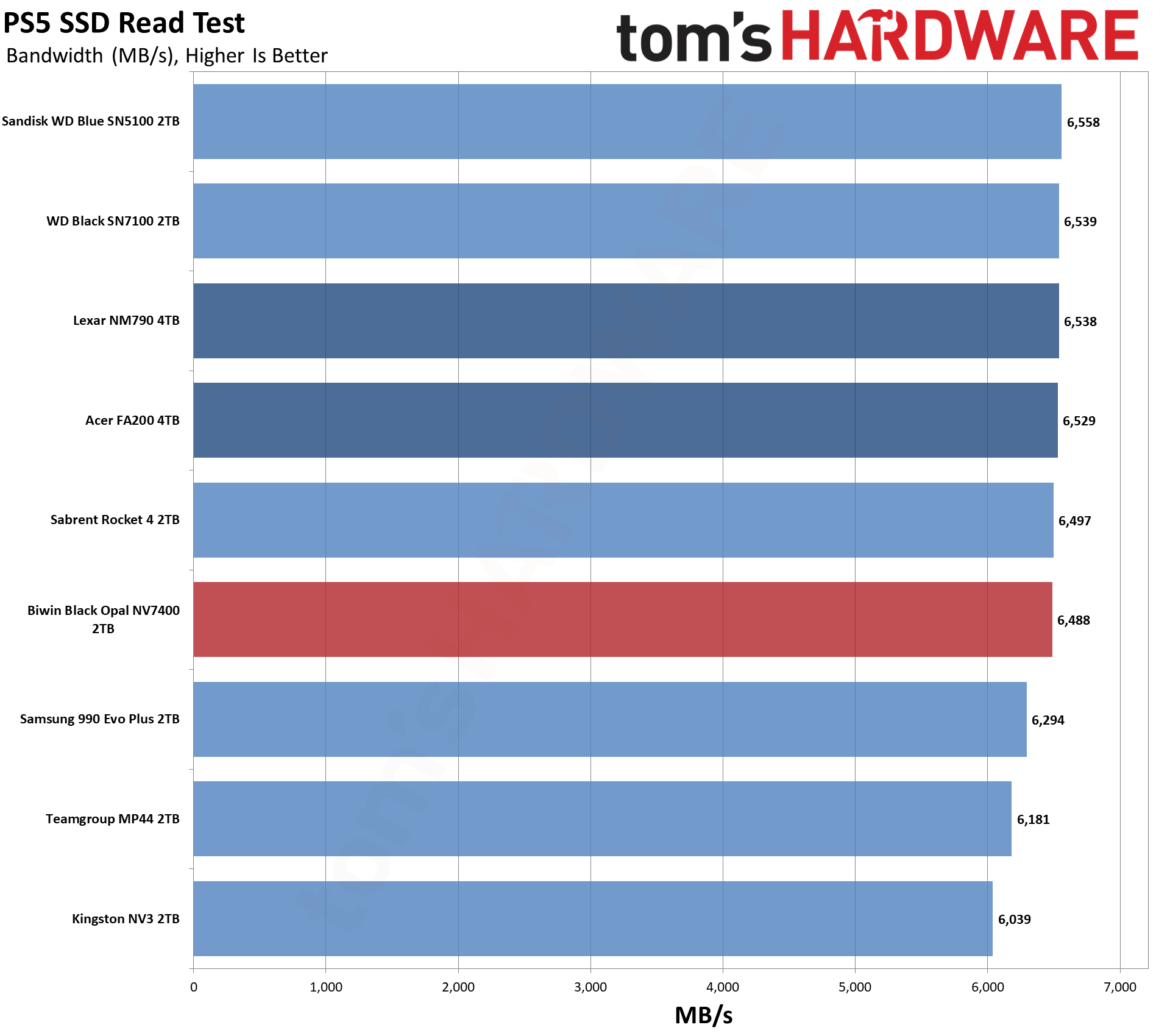

Console Testing — PlayStation 5 Transfers

The PlayStation 5 is capable of taking one additional PCIe 4.0 or faster SSD for extra game storage. While any 4.0 drive will technically work, Sony recommends drives that can deliver at least 5,500 MB/s of sequential read bandwidth for optimal performance. In our testing, PCIe 5.0 SSDs don’t bring much to the table and generally shouldn’t be used in the PS5, especially as they may require additional cooling. Check our Best PS5 SSDs article for more information.

Our testing utilizes the PS5’s internal storage test and manual read/write tests with over 192GB of data both from and to the internal storage. Throttling is prevented where possible to see how each drive operates under ideal conditions. While game load times should not deviate much from drive to drive, our results can indicate which drives may be more responsive in long-term use.

The PS5 is not very demanding on storage used for expansion, which is a good thing. You can always save some money by going with a less expensive drive. While we do present performance numbers for the console, there are certain cases where a drive will hitch up on you; the bigger focus should be on cost and reliability. Reliability is difficult to measure, but knowing what hardware you have is a step in the right direction.

For instance, the NV3 is a great budget SSD, but you can never be sure what hardware you’ll get. This puts a lot of faith into your RNG at the time of purchase. As memory markets get tighter, things get dicier, although Kingston is probably more trustworthy than many no-name brands. If you’re not someone who likes gambling, then you are more likely to go with a WD drive, an NM790, or, as the case may be, the NV7400.

Beyond the fact that the hardware is mature and known, we can expect the drive to run relatively cool, which mitigates one potential area of failure. Drives in the PS5 can get hot, and we do generally recommend a heatsink, but if you want something you can just throw in and not worry about, then the NV7400 would fit the bill. Biwin may not be a household name yet, but it has a legacy of providing assistance for some decent OEM drives, which by design need to be reliable.

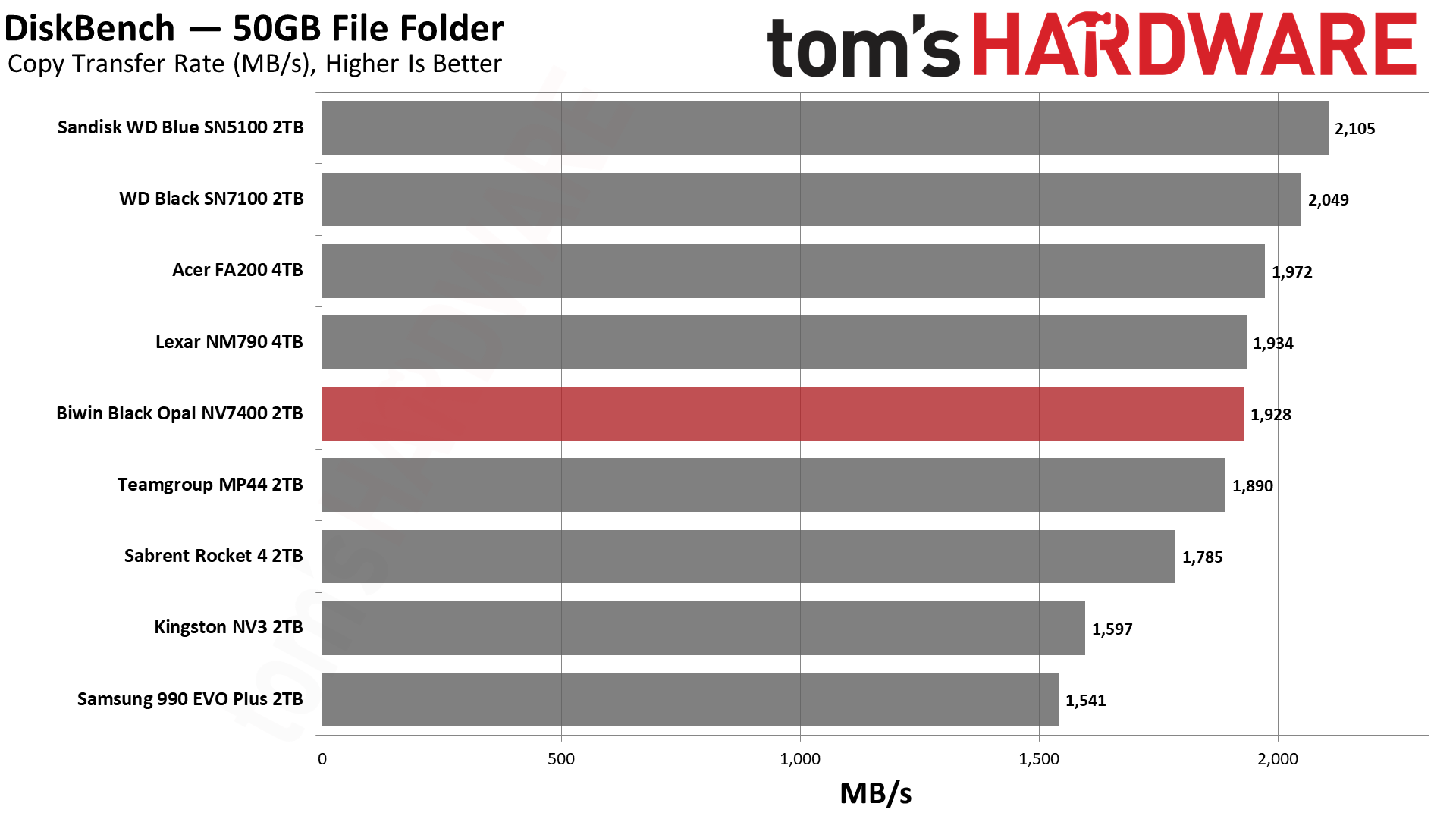

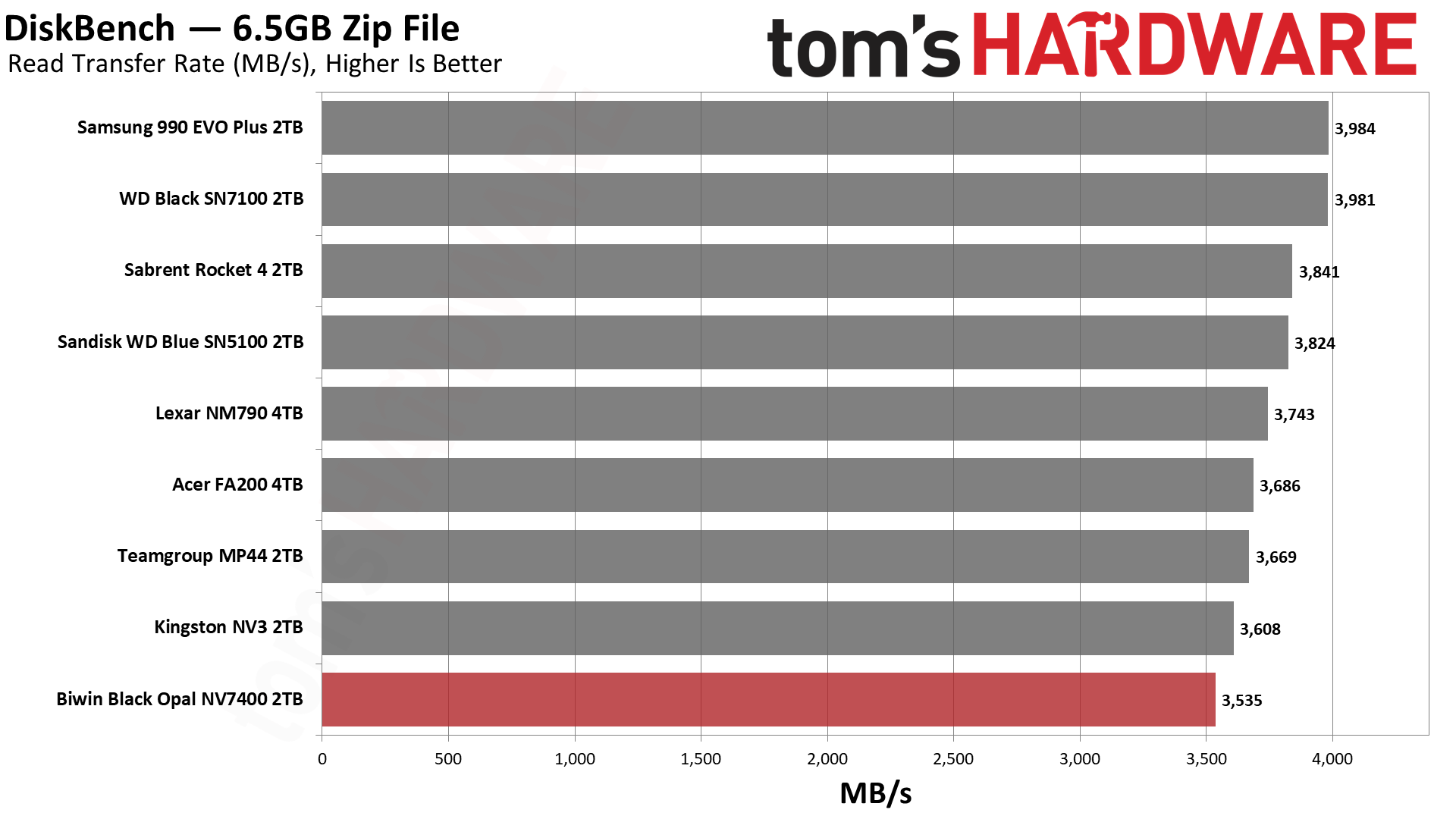

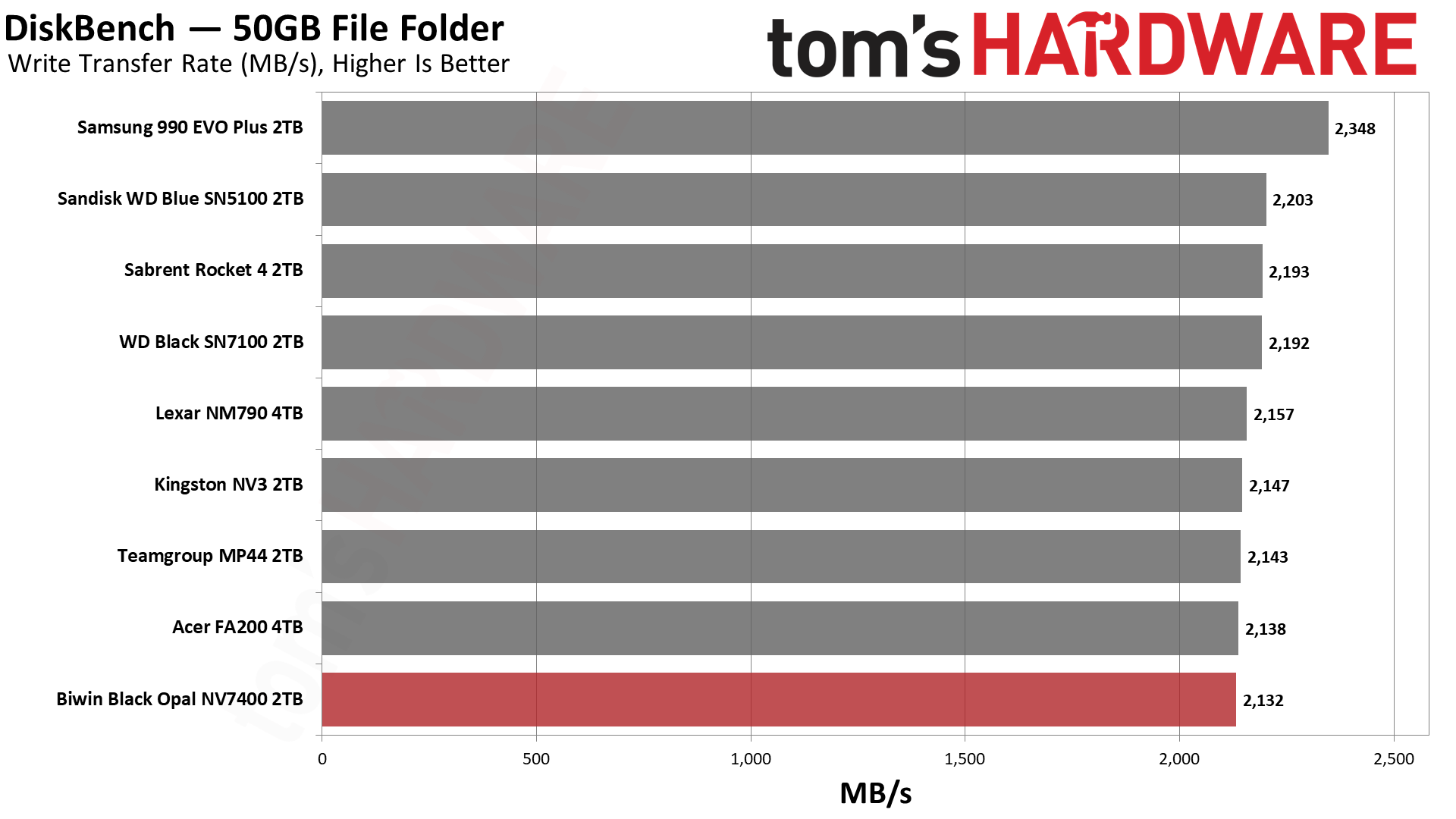

Transfer Rates — DiskBench

We use the DiskBench storage benchmarking tool to test file transfer performance with a custom, 50GB dataset. We write 31,227 files of various types, such as pictures, PDFs, and videos to the test drive, then make a copy of that data to a new folder, and follow up with a reading test of a newly-written 6.5GB zip file. This is a real world type workload that fits into the cache of most drives.

We like to look at copy performance to get a feel of real-world transfer speeds. You’re not always, or even often, going to be copying to the same drive, but DiskBench breaks it down so you can see reads, writes, and what happens when both occur simultaneously. The drive is ultimately limited by its write speed, but its ability to handle mixed I/O is an important factor for a storage drive. So, while the NV7400 is dead last in reads and writes, its copy transfer rate is average. It’s right between the NM790 and MP44, which is exactly where we would expect it to be.

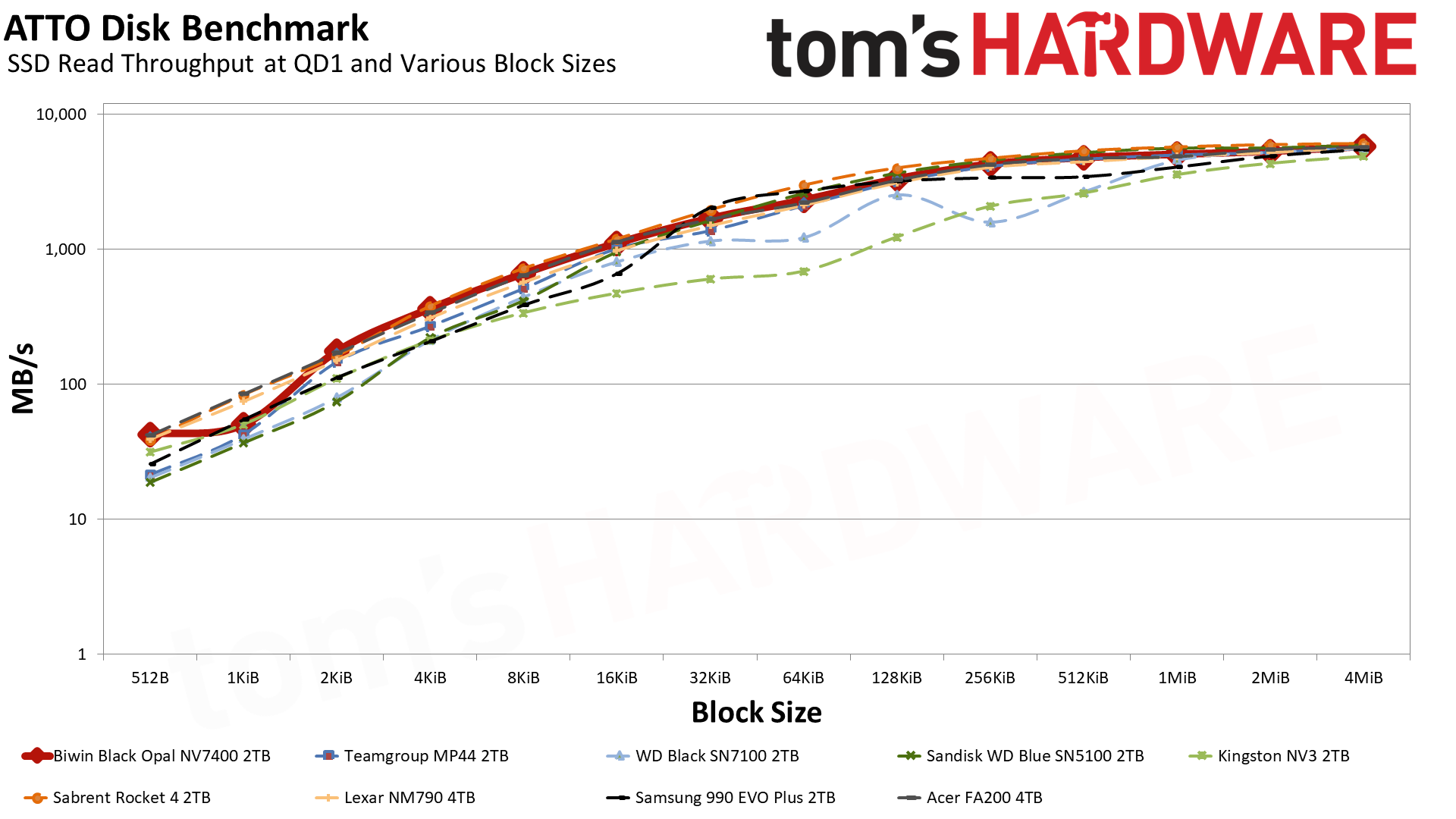

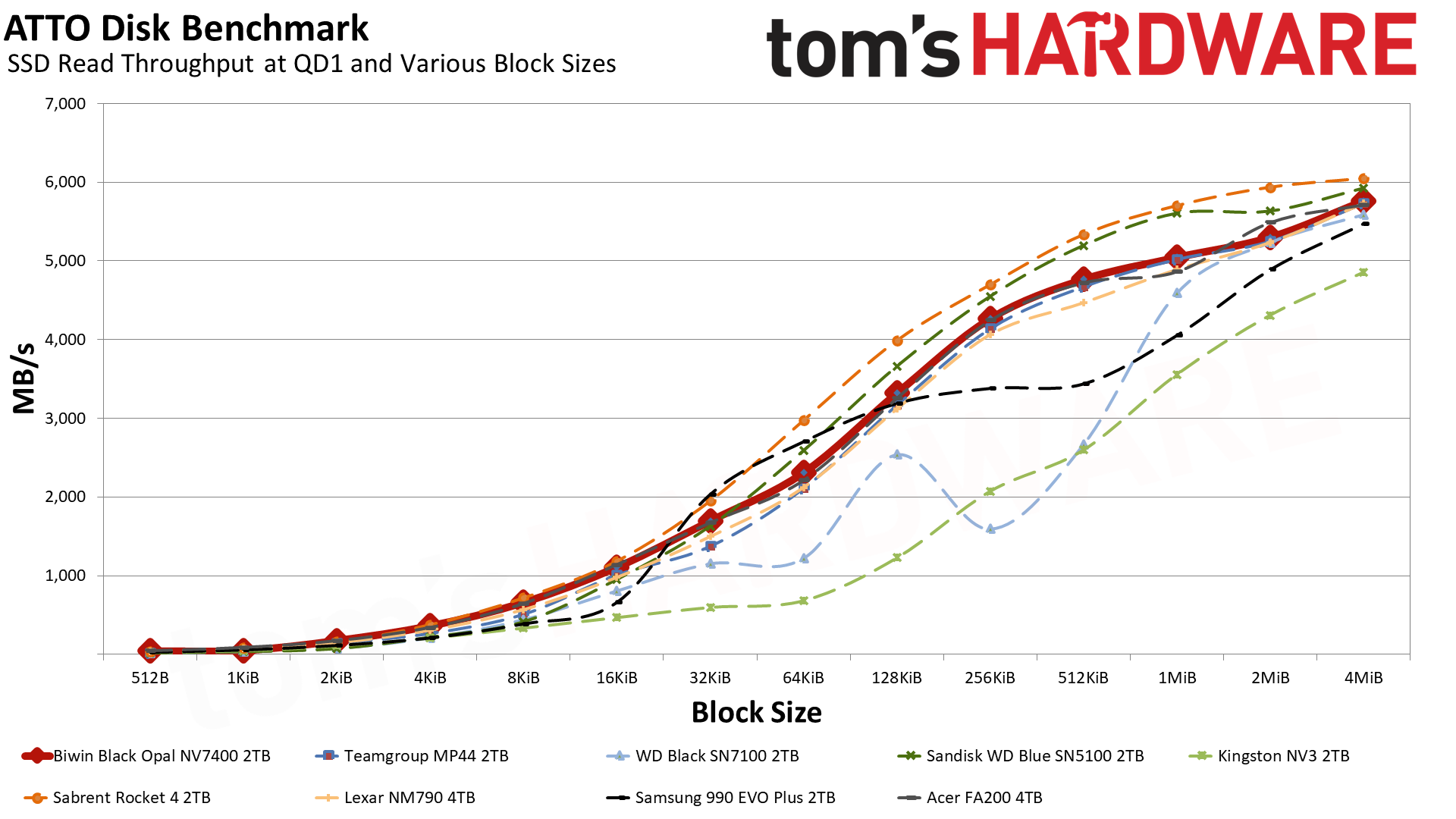

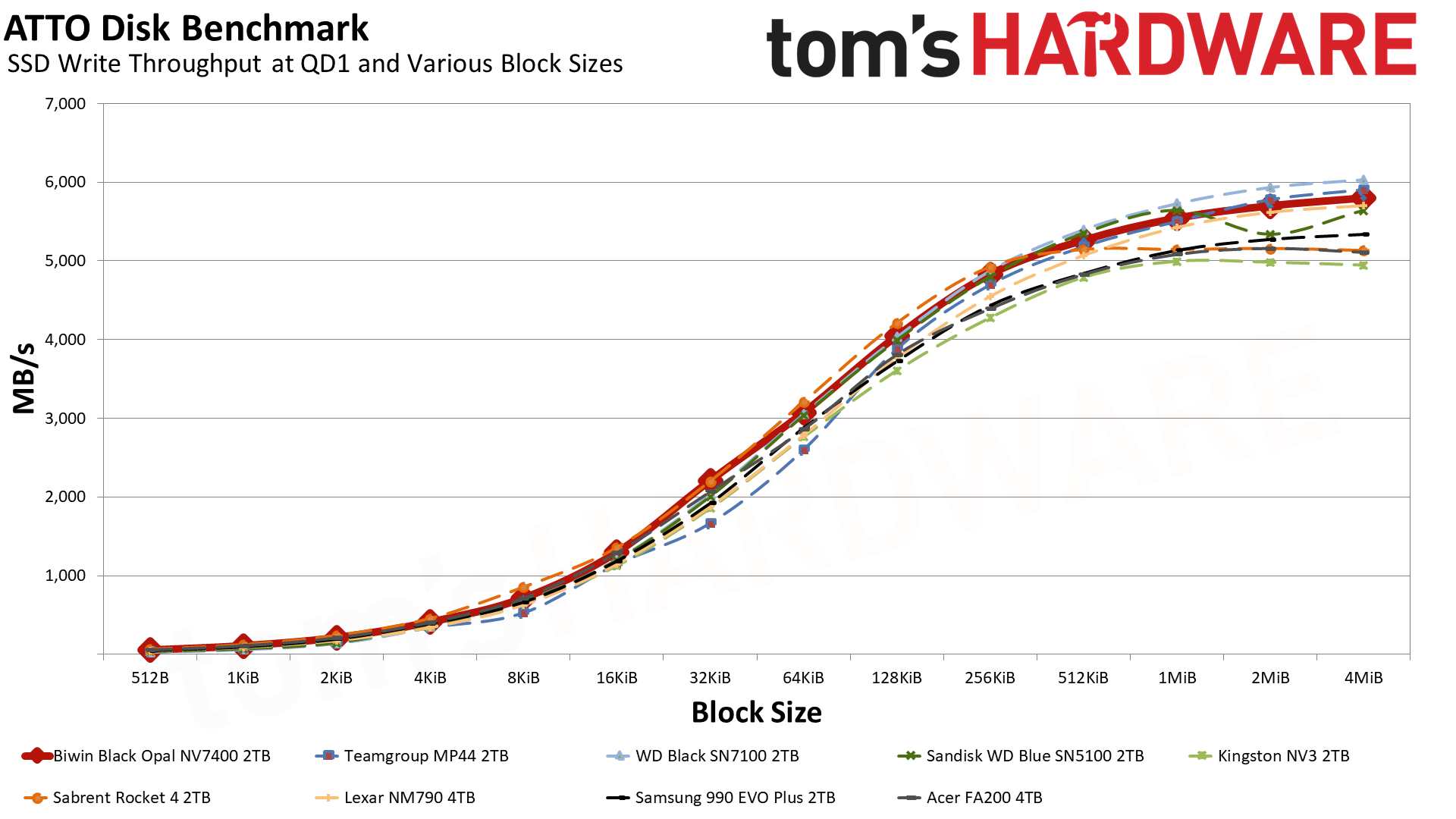

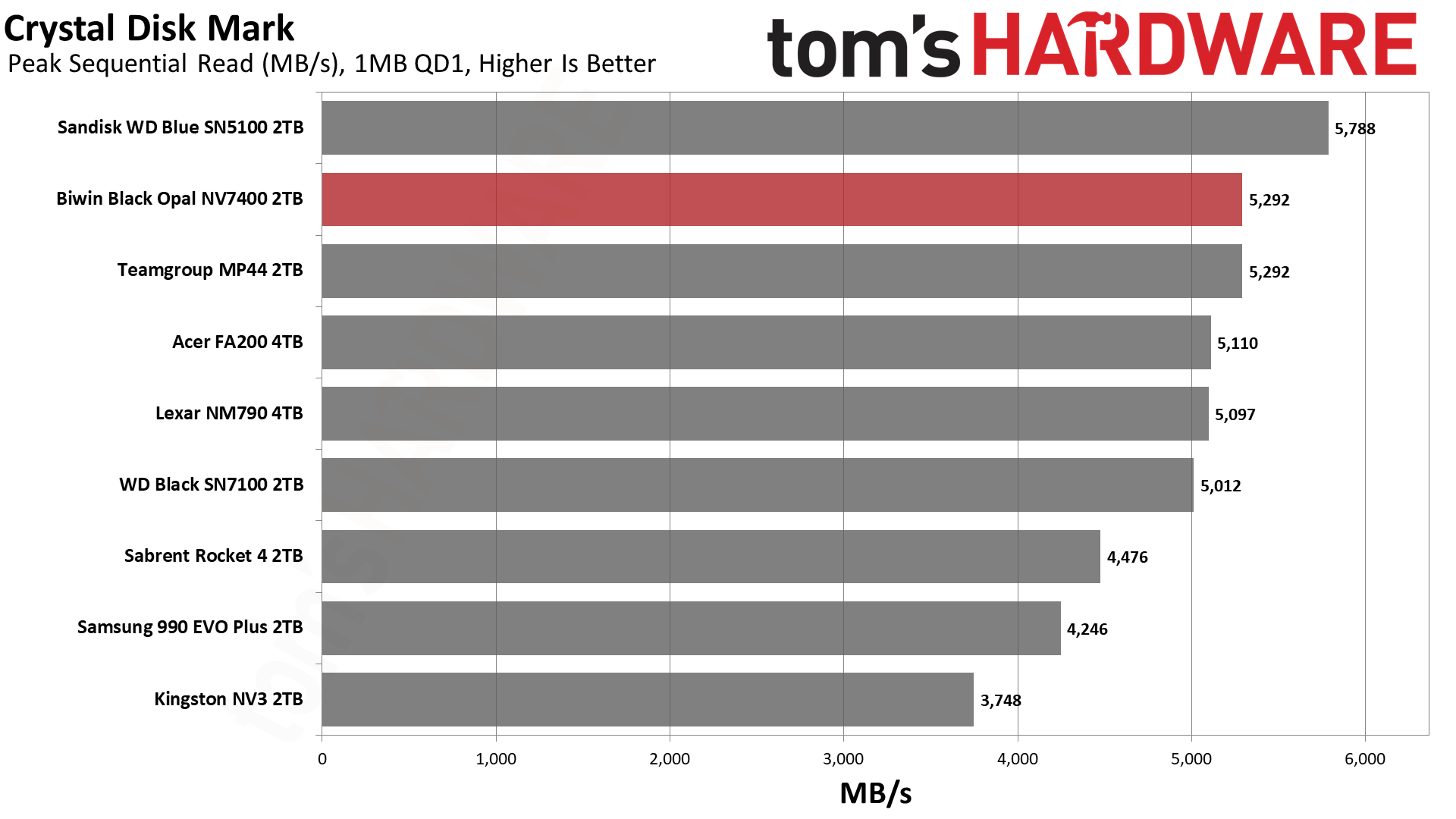

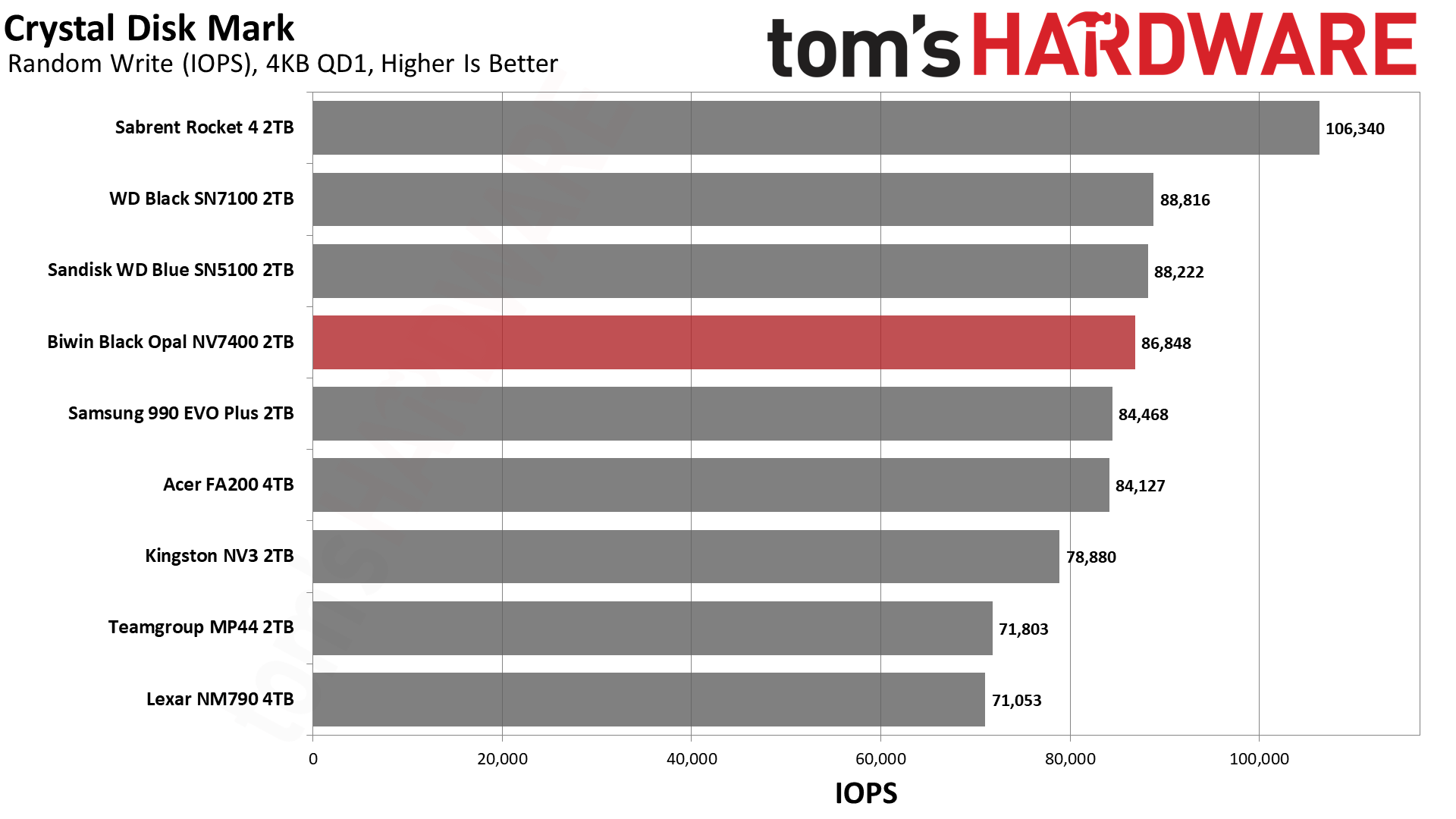

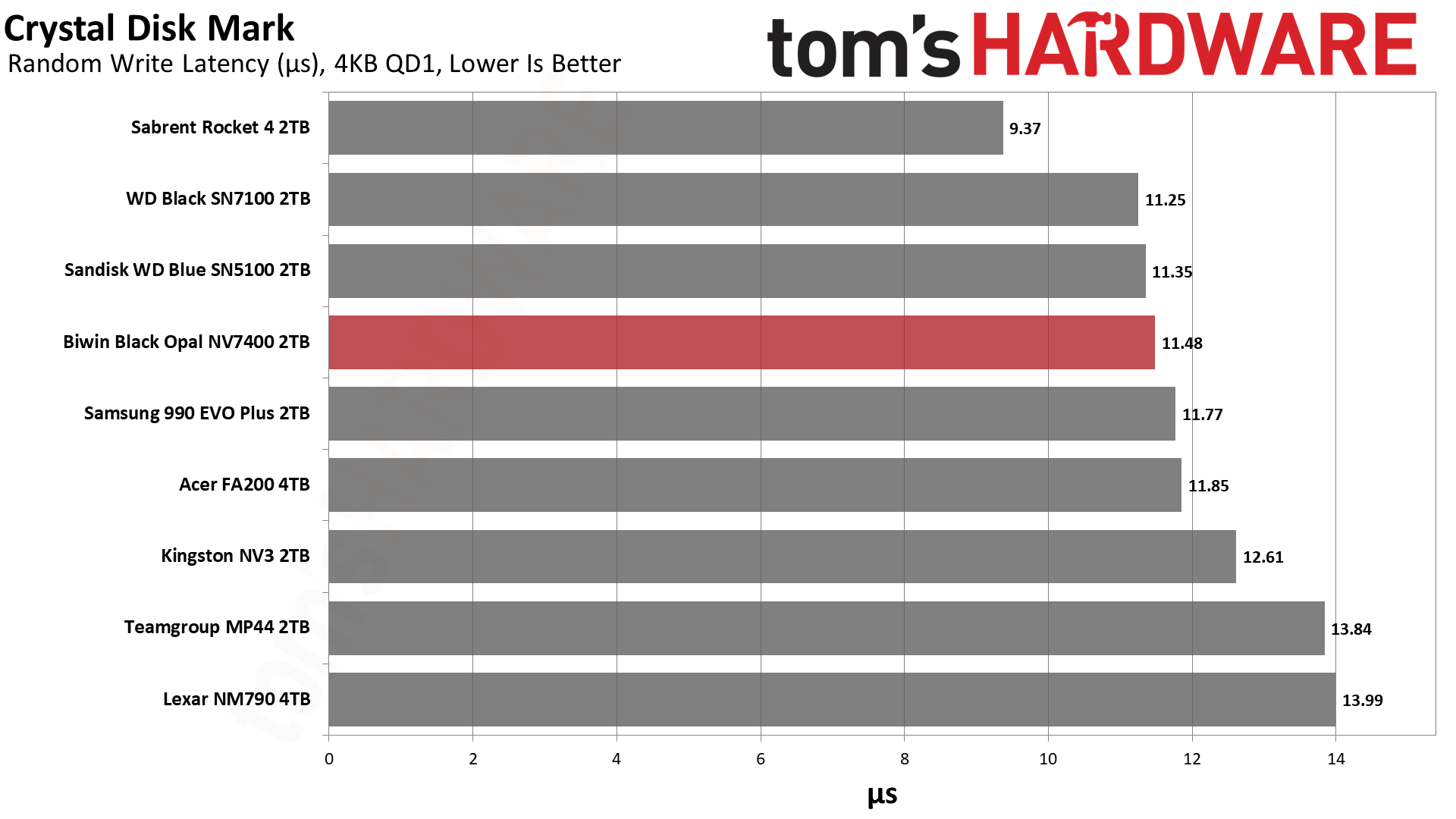

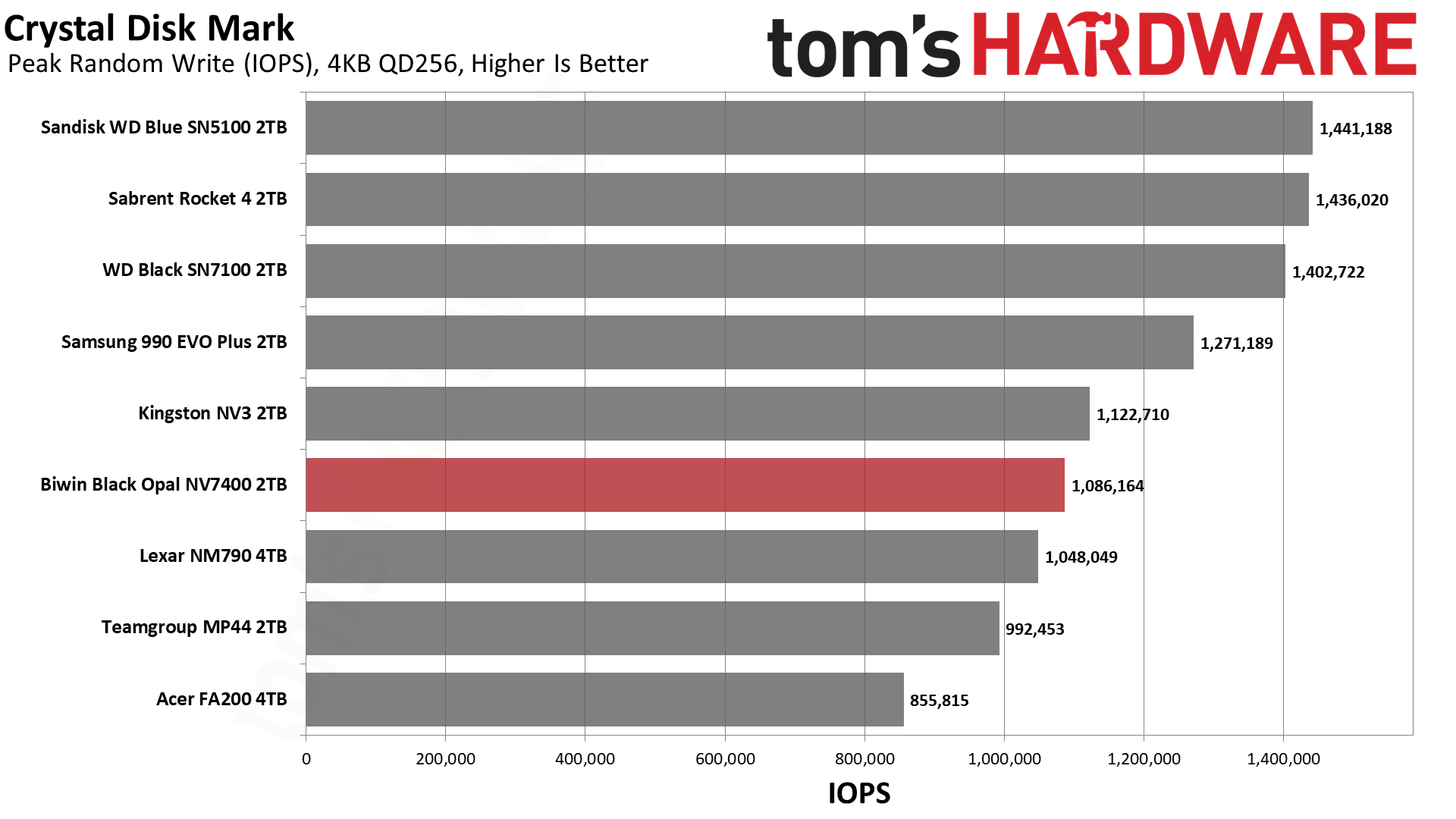

Synthetic Testing — ATTO / CrystalDiskMark

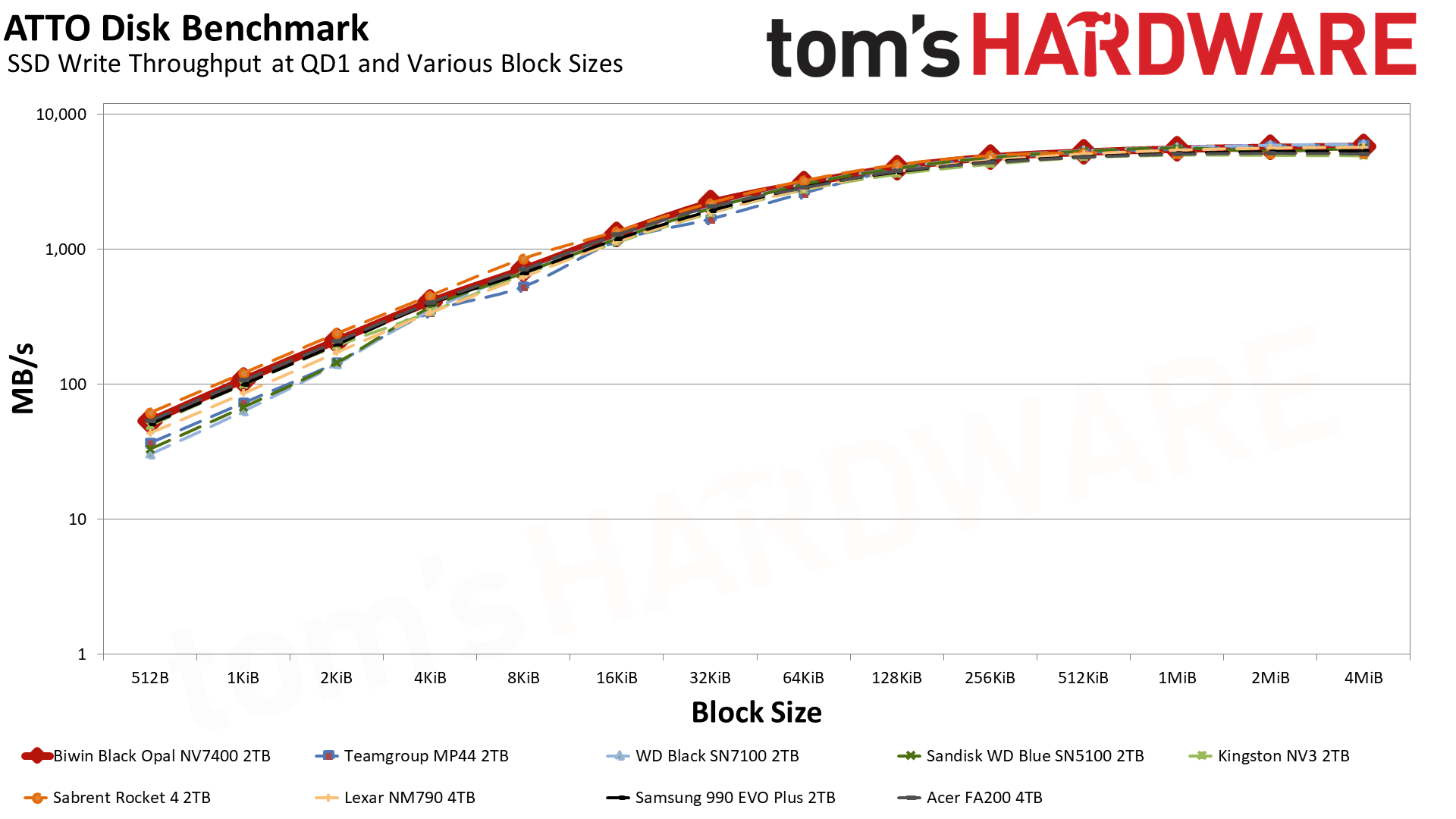

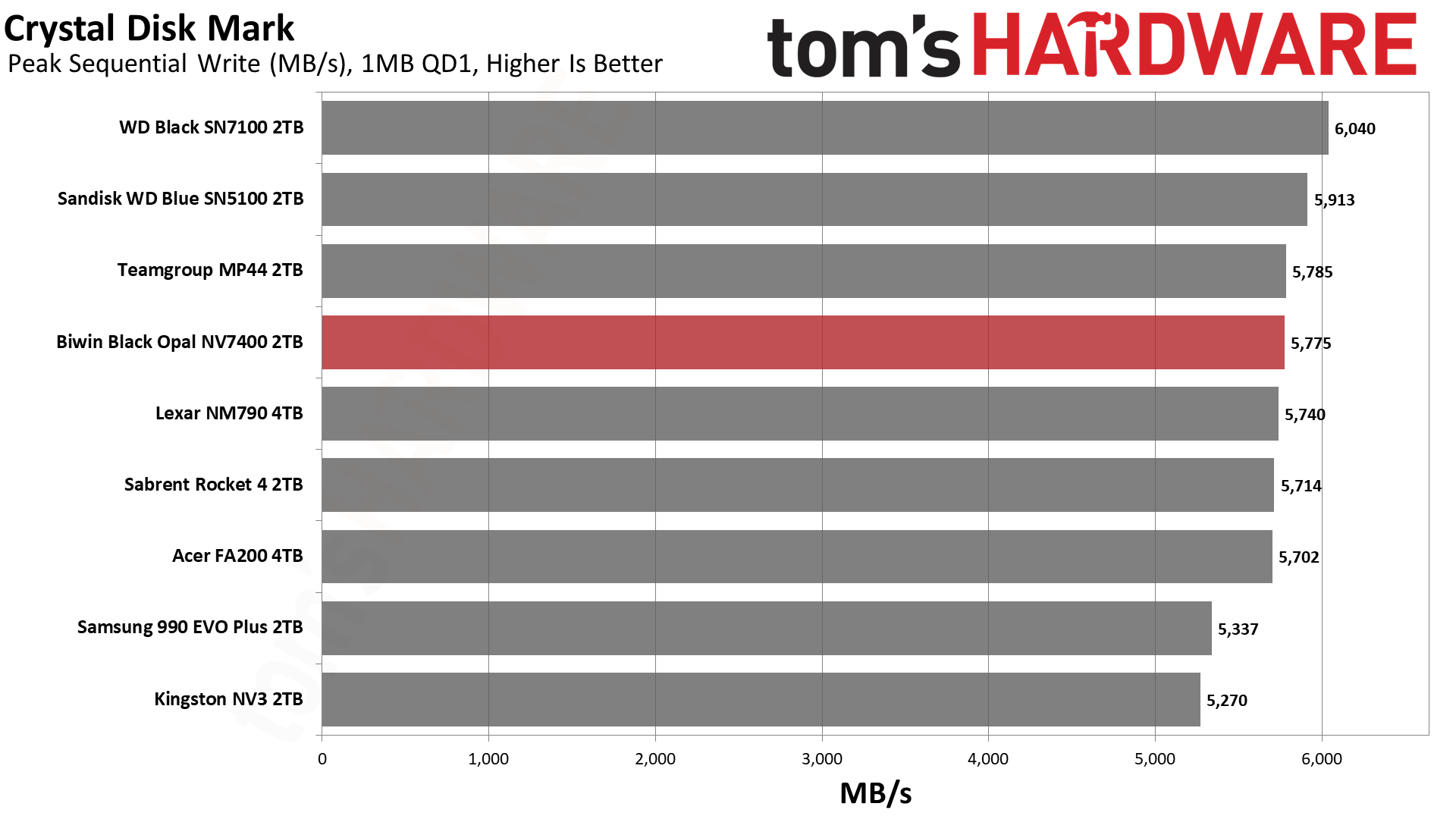

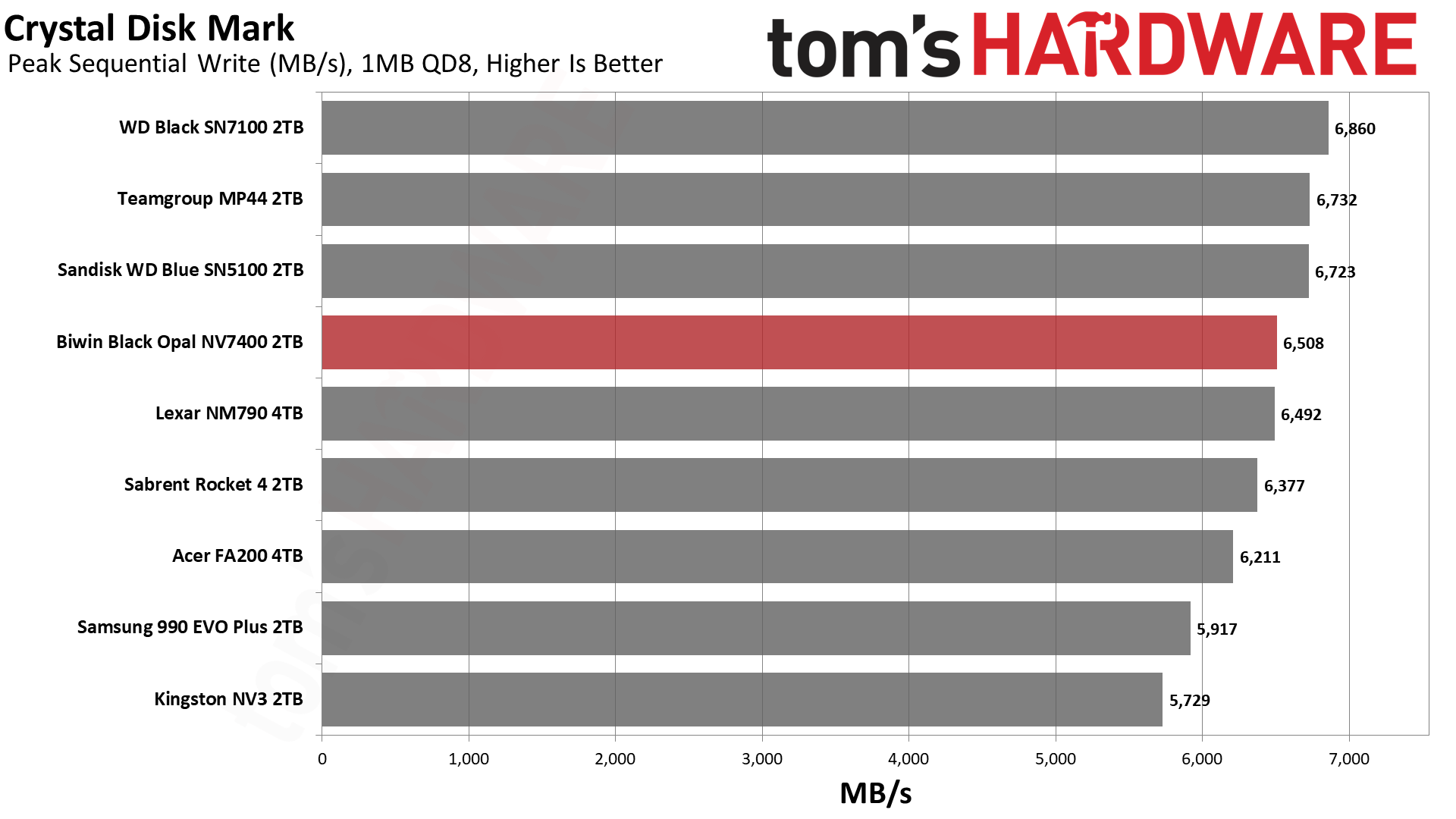

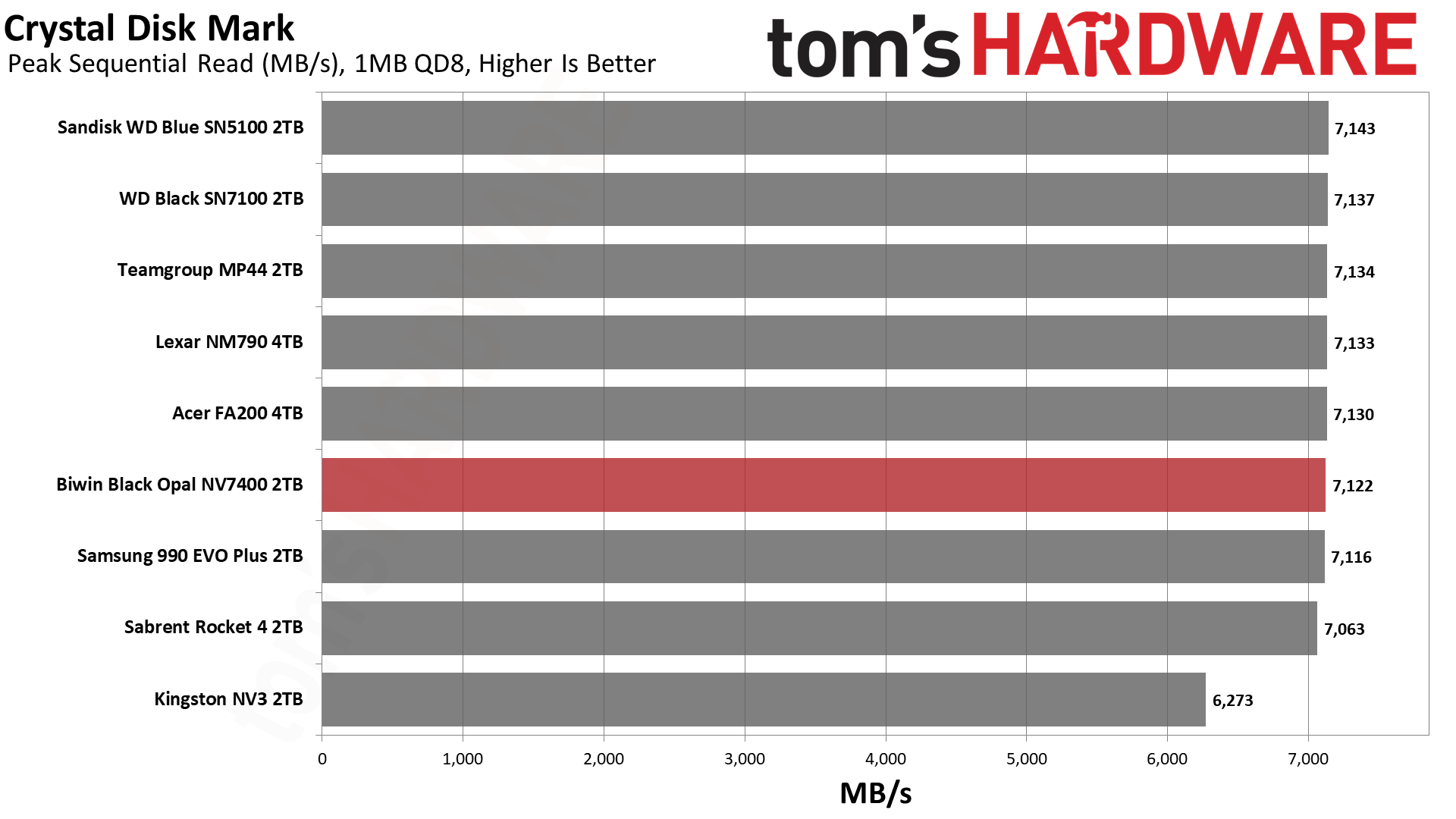

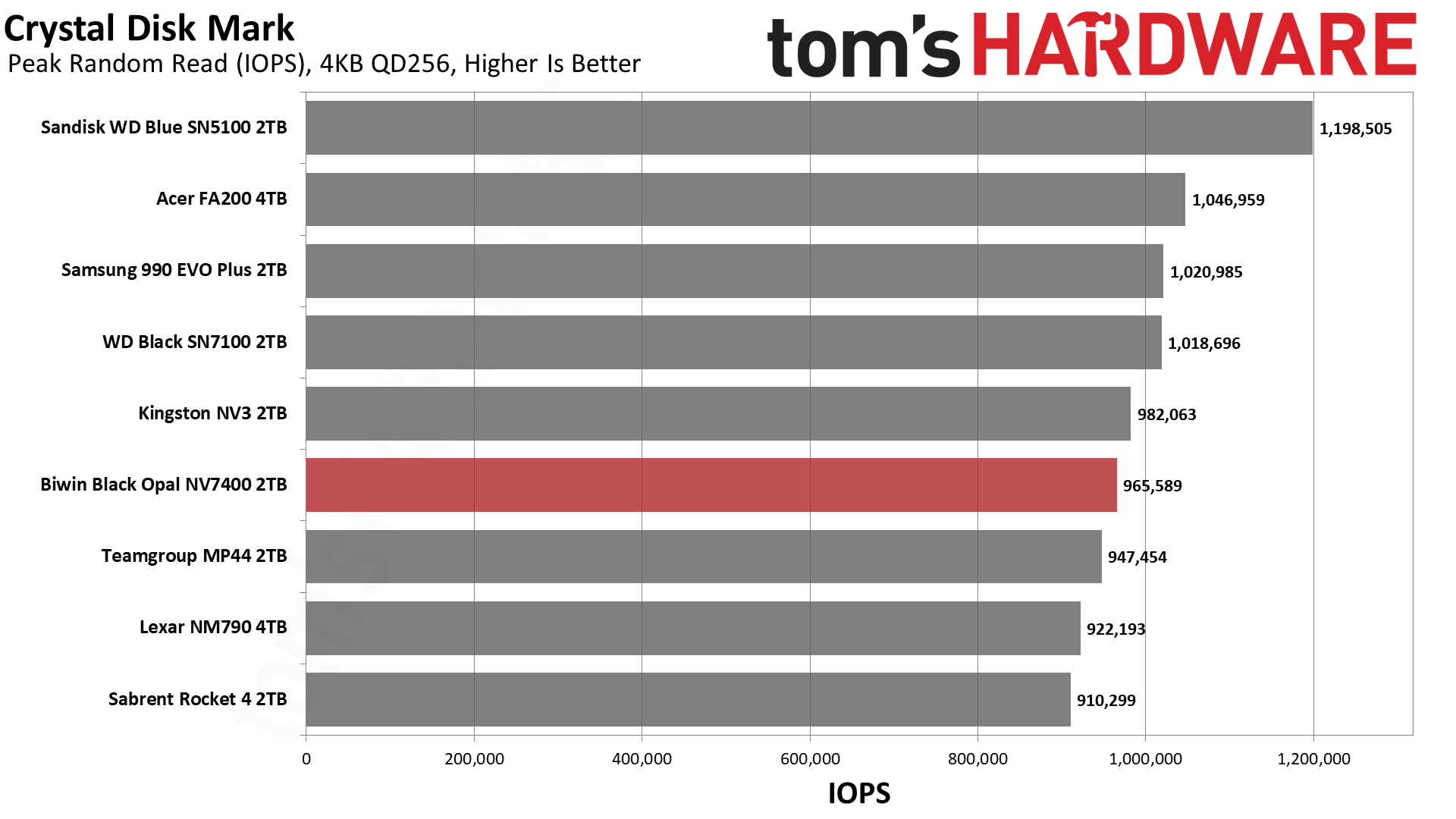

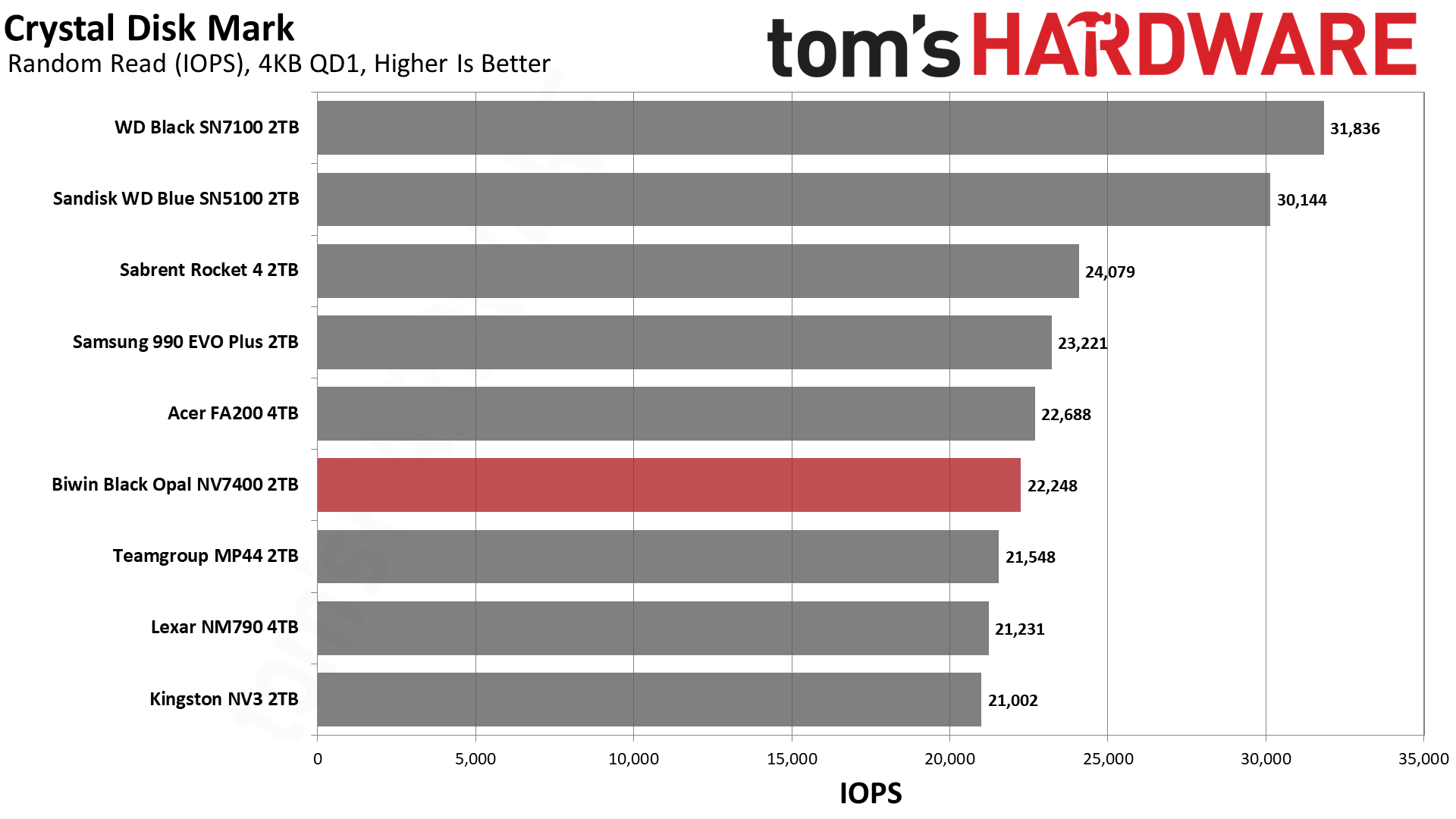

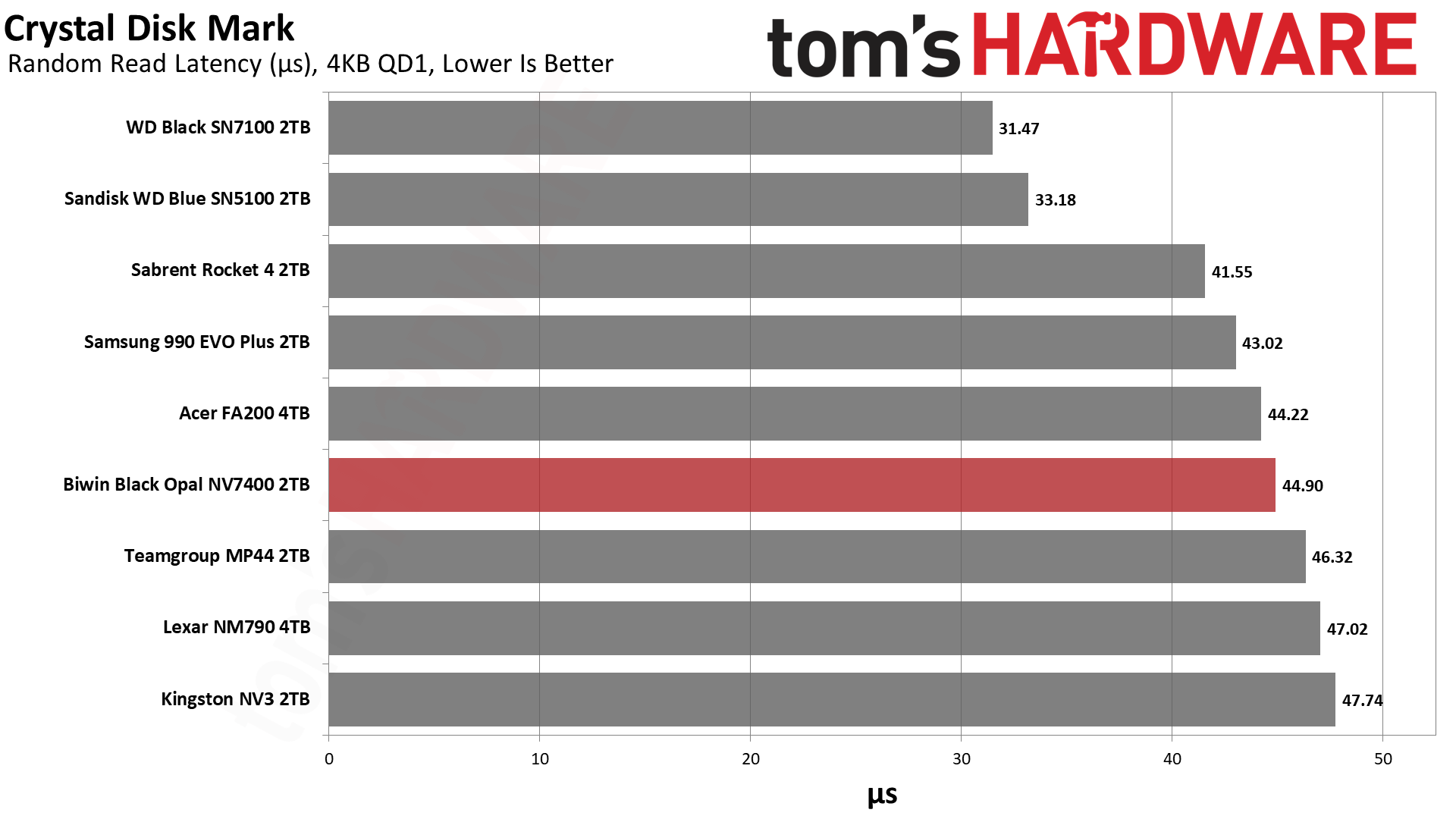

ATTO and CrystalDiskMark (CDM) are free and easy-to-use storage benchmarking tools that SSD vendors commonly use to assign performance specifications to their products. Both of these tools give us insight into how each device handles different file sizes and at different queue depths for both sequential and random workloads.

Let’s start with ATTO, a benchmark that tests performance across a range of block sizes to represent different transfer speeds. The NV7400 is very much in line with the MP44 and NM790, although the latter is a bit below the first two. This is as expected since the 4TB NM790 has to deal with more overhead due to having more flash. The NV7400 actually performs very close to the MP44. YMTC and Micron’s 232-layer TLC flashes have a suspicious amount of similarities, including the same plane count of six. Up to this point, we can say they are interchangeable, even with a Maxio controller, where there has potentially been more time for YMTC flash optimization.

We do start to see some divergence in CrystalDiskMark. While sequential performance is more or less the same at QD1, random read and write performance are both better on the NV7400. This suggests that the NV7400 will feel more responsive, although this can be difficult to tell in daily use. It’s true that we’re working with a mature and updated controller on the NV7400, which means there may have been an optimization pass or two since we reviewed the other two drives. Nevertheless, the performance gap is enough that we would call it for the Micron flash – we’d take the NV7400 over the typical YMTC-based drives, all else being equal.

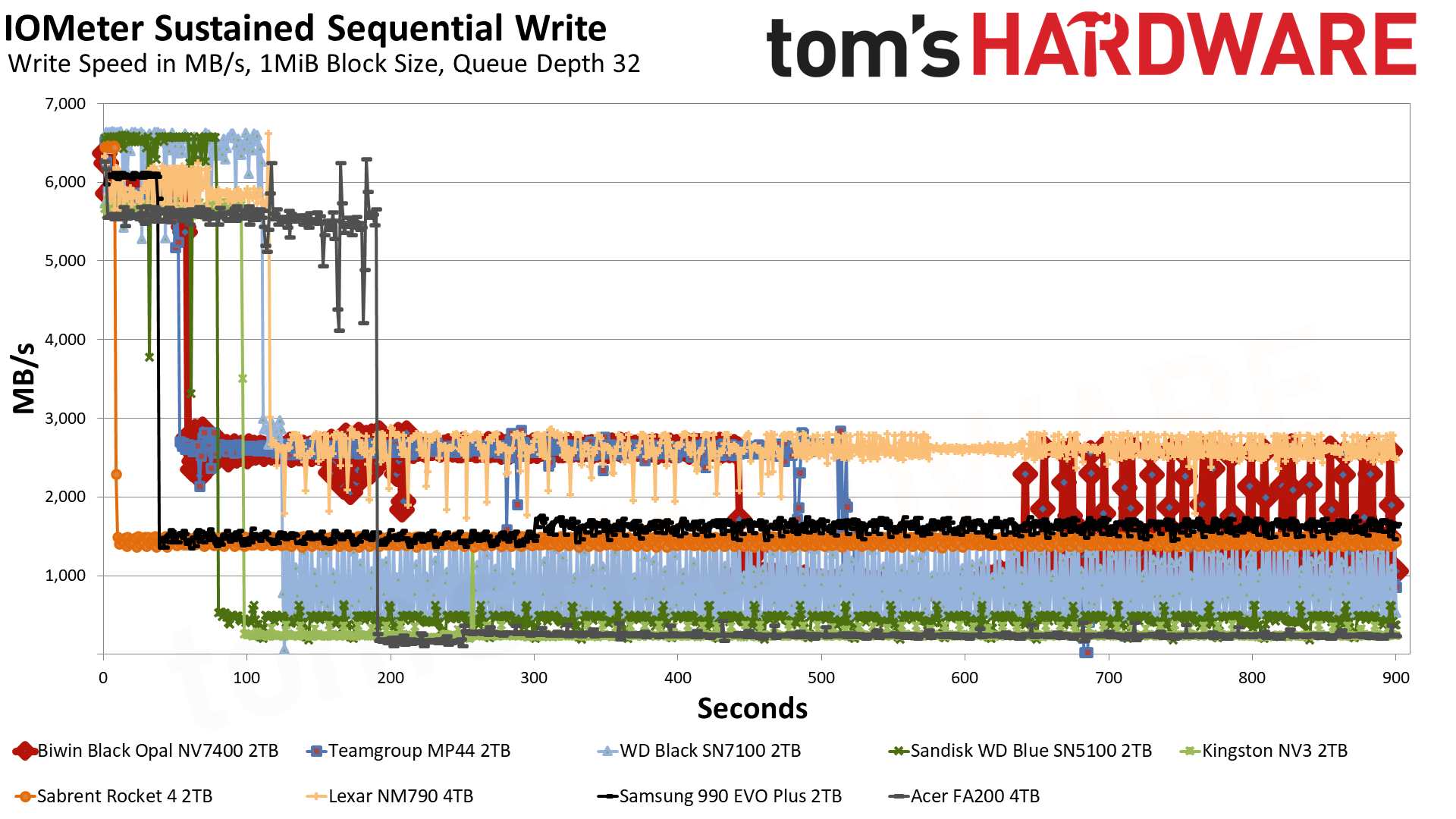

Sustained Write Performance and Cache Recovery

Official write specifications are only part of the performance picture. Most SSDs implement a write cache, which is a fast area of pseudo-SLC (single-bit) programmed flash that absorbs incoming data. Sustained write speeds can suffer tremendously once the workload spills outside of the cache and into the "native" TLC (three-bit) or QLC (four-bit) flash. Performance can suffer even more if the drive is forced to fold, which is the process of migrating data out of the cache in order to free up space for further incoming data.

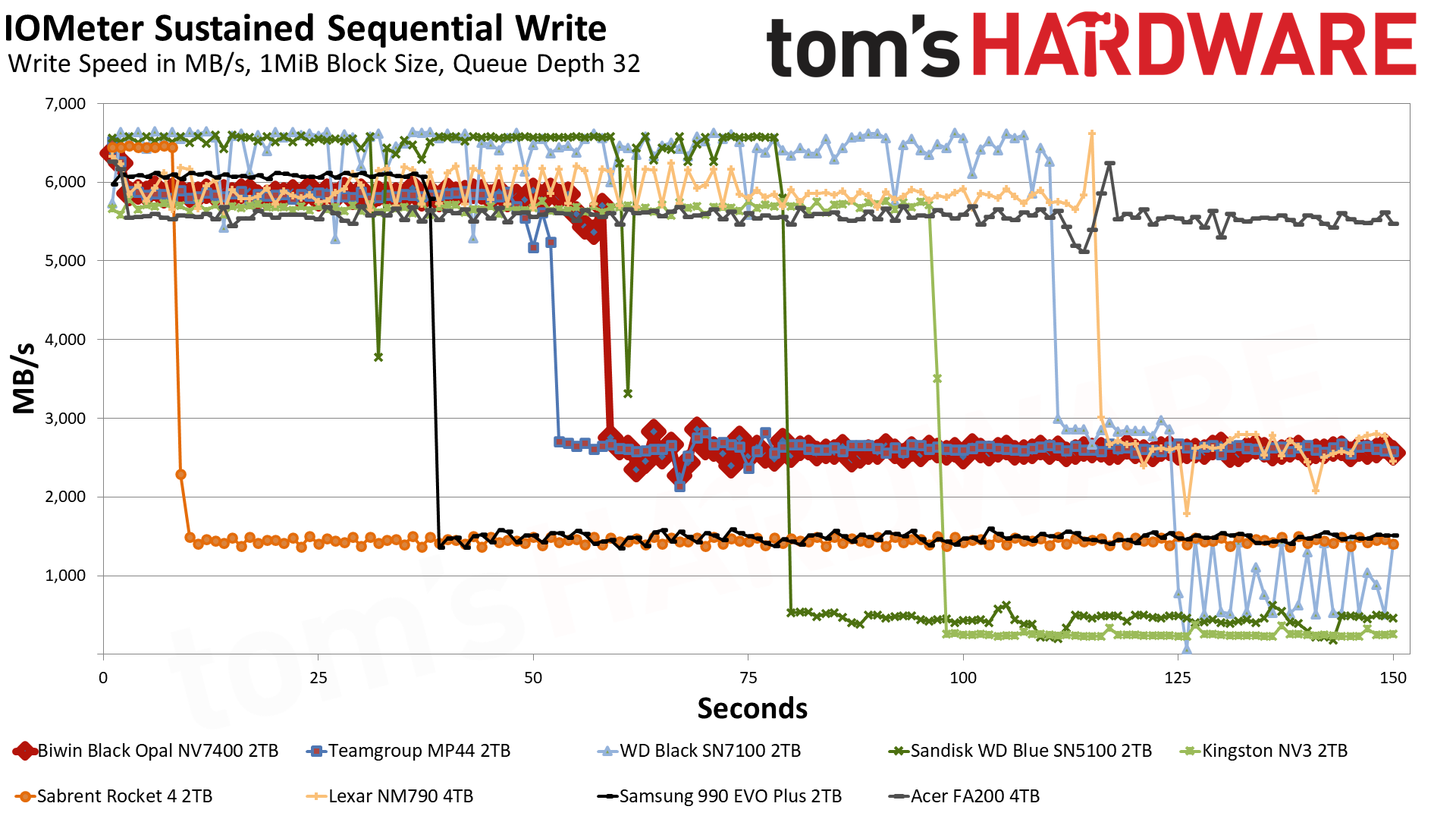

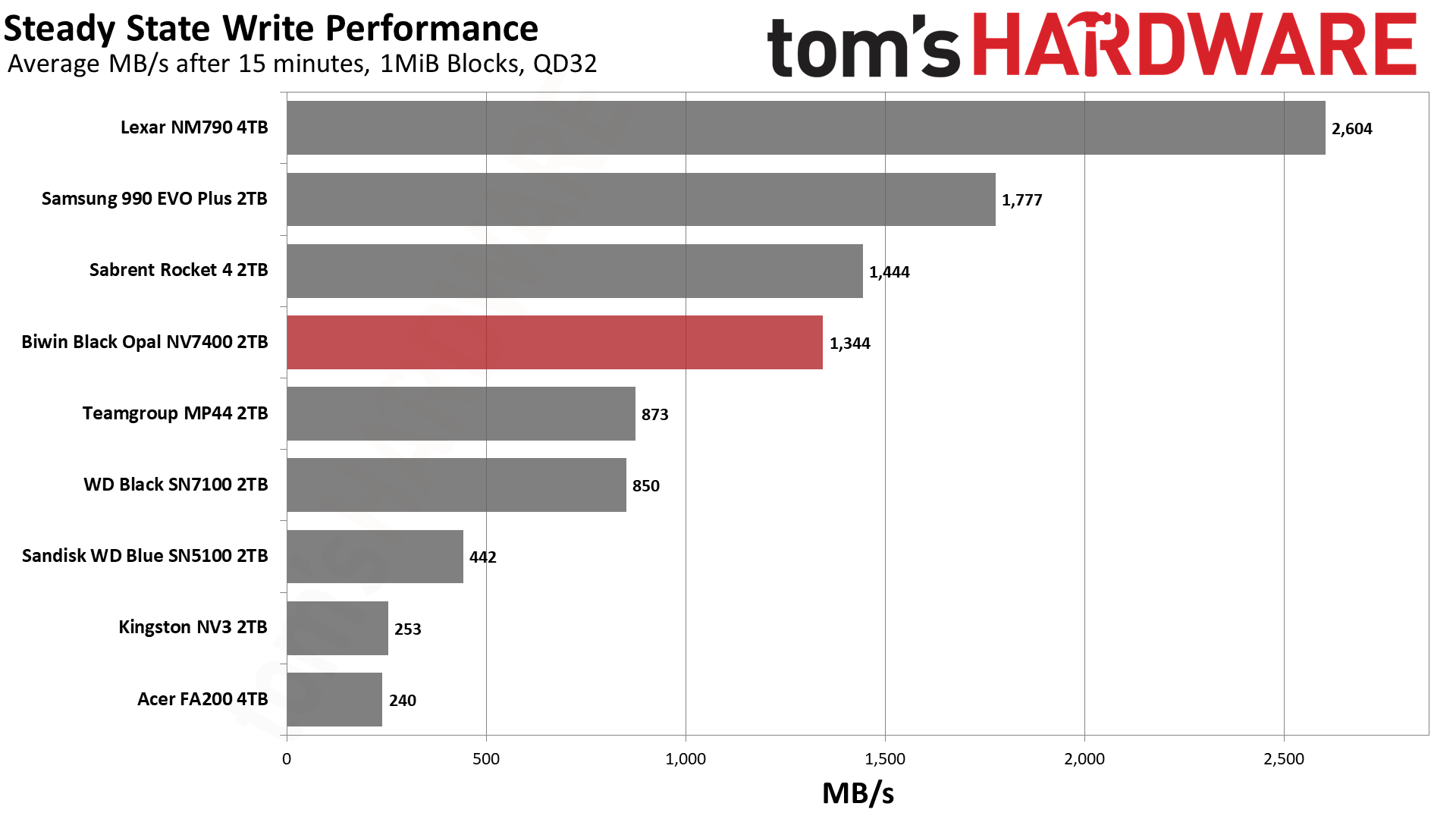

We use Iometer to hammer the SSD with sequential writes for 15 minutes to measure both the size of the write cache and performance after the cache is saturated. We also monitor cache recovery via multiple idle rounds. This process shows the performance of the drive in various states as well as the steady state write performance.

Modern SSDs have multiple write performance states that depend upon active conditions. Usually, we see three such states: writes in the super-fast pSLC cache, writes that are going directly to the flash in its native mode, and writes that are held up as the drive attempts to copy or fold data over from the cache to the native flash. These states are by no means ironclad, and in fact, the drive will attempt to juggle multiple states at once as it needs to maintain performance and free space simultaneously, something made more challenging by the fact that the cache mode trades capacity for speed. It’s a temporary and limited boost, and the size of the cache is also taken as a tradeoff for sustained performance. You may like the numbers on the box, but they might not always be there.

The NV7400 starts in the pSLC cache with writes of 5.84 GB/s for 58 seconds. Doing the math, this implies a 339GB cache, which is mid-sized by today’s standards. As this drive is using 3-bit TLC, the maximum cache size is approximately one-third the listed drive capacity, and this cache is about half of that. Drives like the WD Blue SN5100 have a larger cache – it’s QLC-based, so the tradeoff is 4:1, though – and others, like the Rocket 4, have smaller caches. Larger caches may have reduced performance in the long run, while smaller ones can deliver better write consistency. The NV7400 is somewhere in the middle, which is a good place to be.

After the cache is exhausted, the NV7400 starts writing to TLC at around 2.6 GB/s. This is pretty fast, especially for a four-channel controller. This is more or less even with the NM790 and MP44. We’ve mentioned how similar YMTC and Micron 232-Layer TLC flash perform, although in some technical documents, the former is supposed to write faster. In practice, with the same controller, they are more or less dead even. Consistency is such that we get different steady state write speeds, though. For instance, the NM790 is almost twice as fast as the NV7400, but this kind of makes sense as it has twice the flash – if you can interleave more flash, you can reach higher speeds. This makes sense if performance is otherwise unbound. The MP44, on the other hand, performs significantly worse. The truth is, all three drives put out roughly the same performance where it matters, so it’s important to be careful about reading too much into any one number.

In fact, all three drives end up in a folding state below 900 MB/s. The folding state occurs when the drive is forced to move data over from pSLC to TLC before it can accept more incoming writes. There are reasons to push writes through the cache first – not only for speed, but because it can reduce wear in many cases. Writing straight to TLC is suboptimal. If the drive is busy moving data over, its inherent speed is usually going to be less than half of its TLC speed because you’re introducing an extra write pass for data that’s already been written, and this has to be read and verified first. Interruptions, such as trying to read the data while such writes are being processed, delay this action further and increase latency to the detriment of the user experience.

To put it succinctly, you want to avoid hitting the drive this hard, but it’s good to know how the drive handles itself in such a scenario. This is one reason that drives must be preconditioned before being reviewed, as the performance you get out of the box or under ideal conditions tells you little about how the drive will perform over a longer period of time. SanDisk recently added an optimized preconditioning process to flexible I/O (FIO), which enables much faster preconditioning by applying a mathematical algorithm so that a single write pass can simulate multiple passes, specifically with random writes. This makes sense for enterprise drives, which lack a pSLC cache, especially as preconditioning can take a long time with very large drives. For consumer drives like the ones we review, things are a bit easier. Our write saturation testing helps reveal where the drive might be weak if you’re someone who does a lot of transfers, which do tend to be sequential in nature. We should point out that other manufacturers – Western Digital and Seagate, to name two – have preconditioning patterns for a variety of workloads, but our analysis is simplified.

The bottom line is that the NV7400 does a pretty good job of balancing tradeoffs, and you’re not losing anything with it over the NM790 or MP44. In fact, the NV7400 performs more than adequately when put up against any drives in its class. This makes it great even if you intend to use it as a secondary drive.

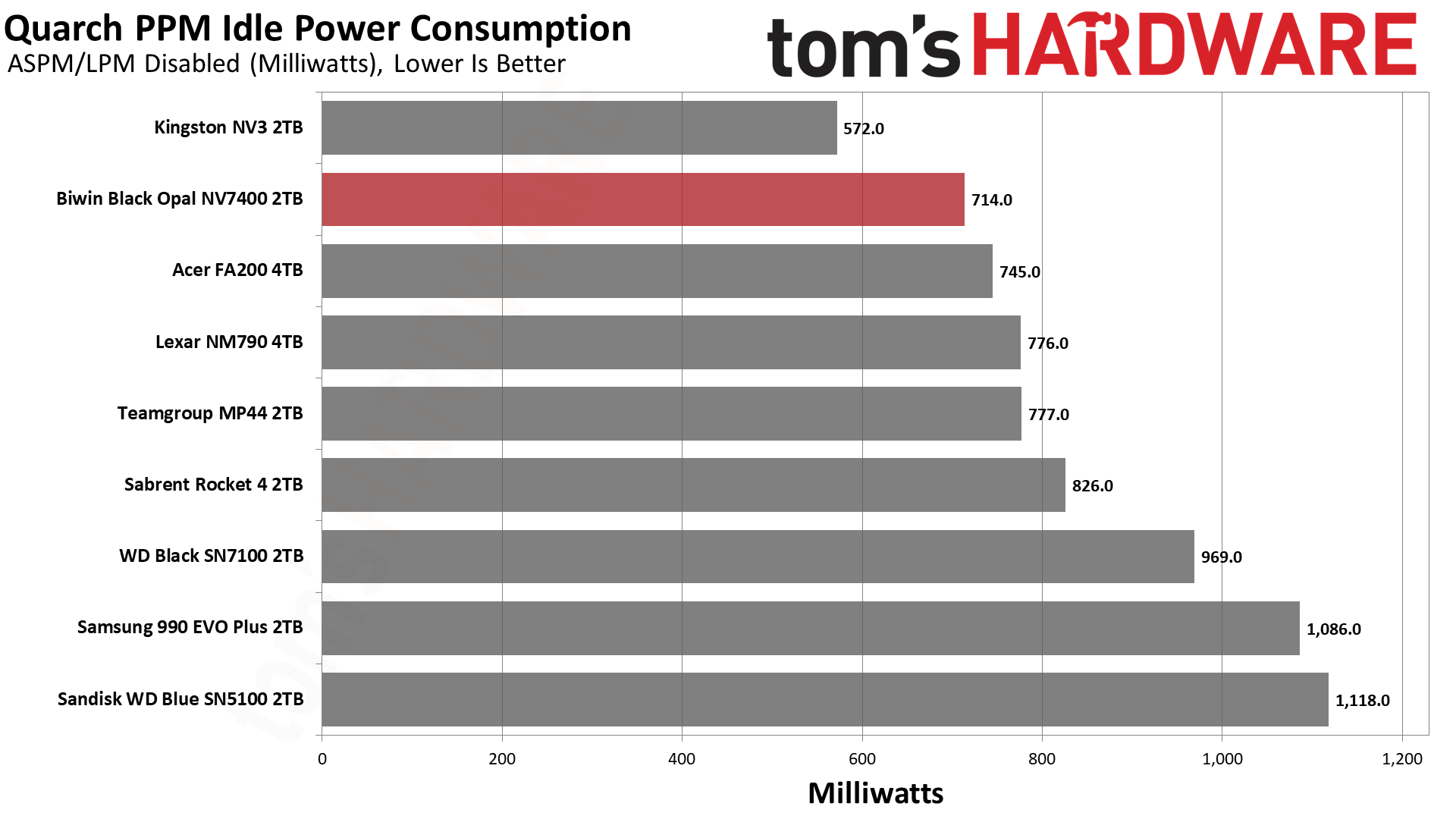

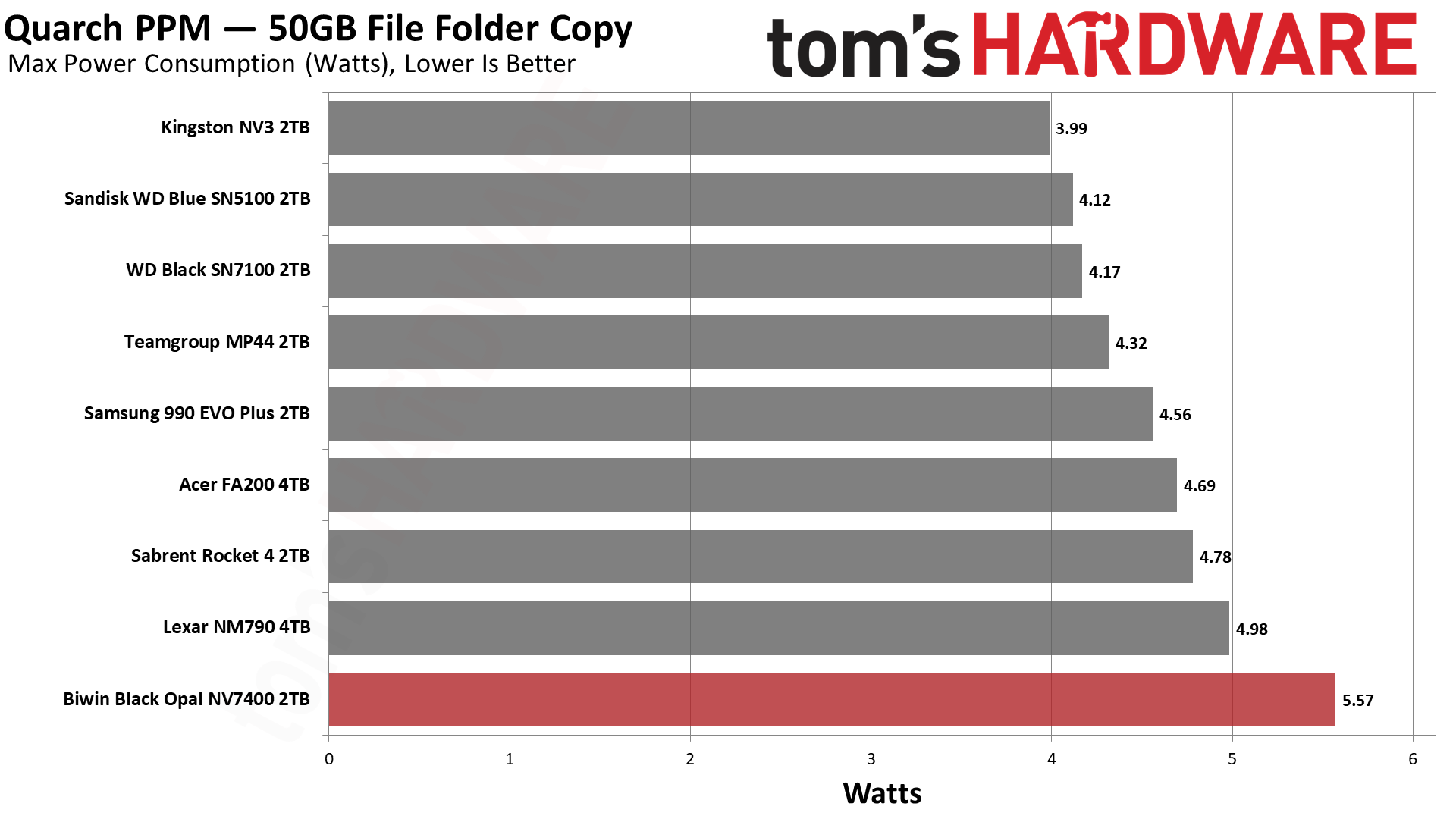

Power Consumption and Temperature

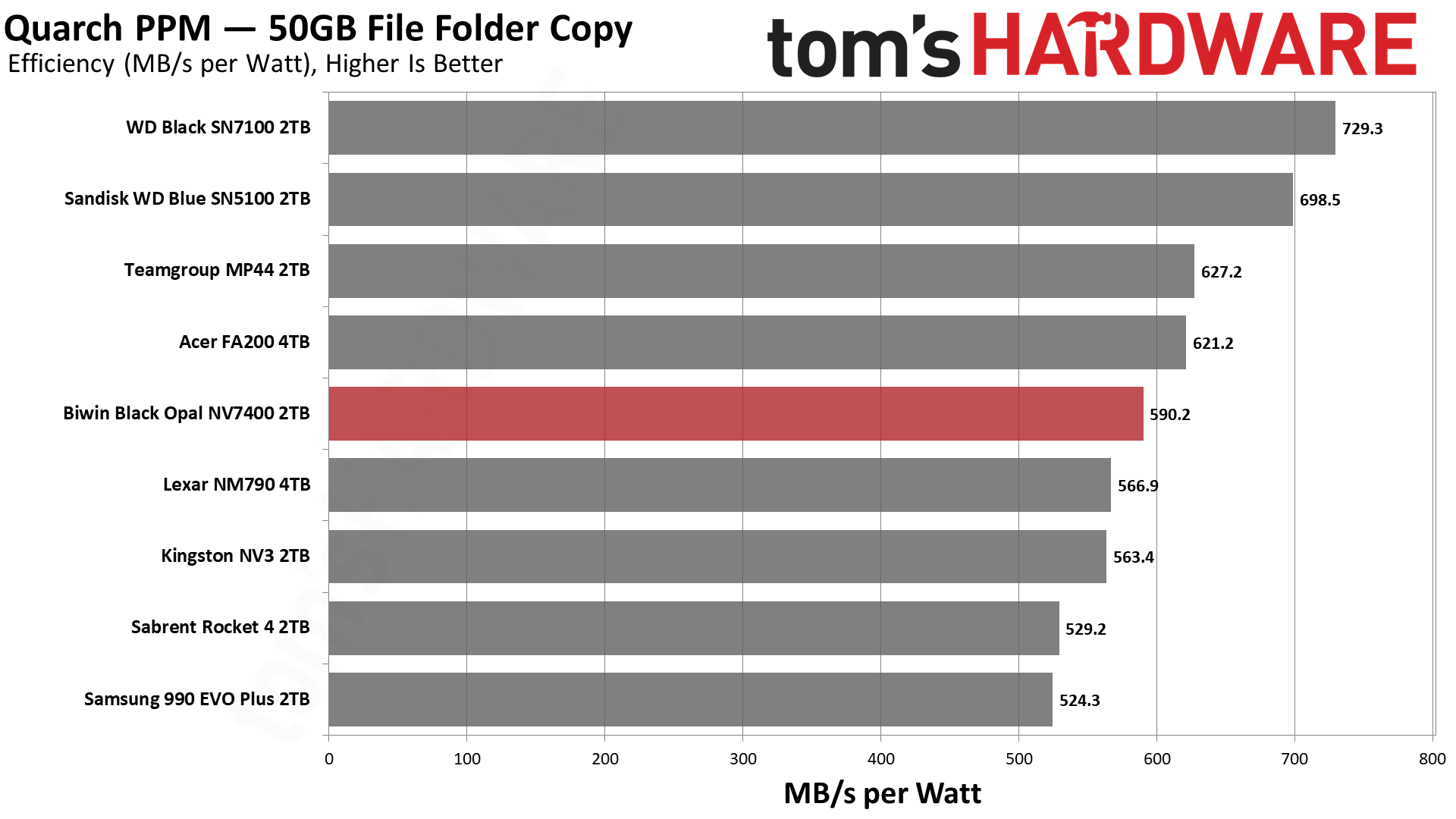

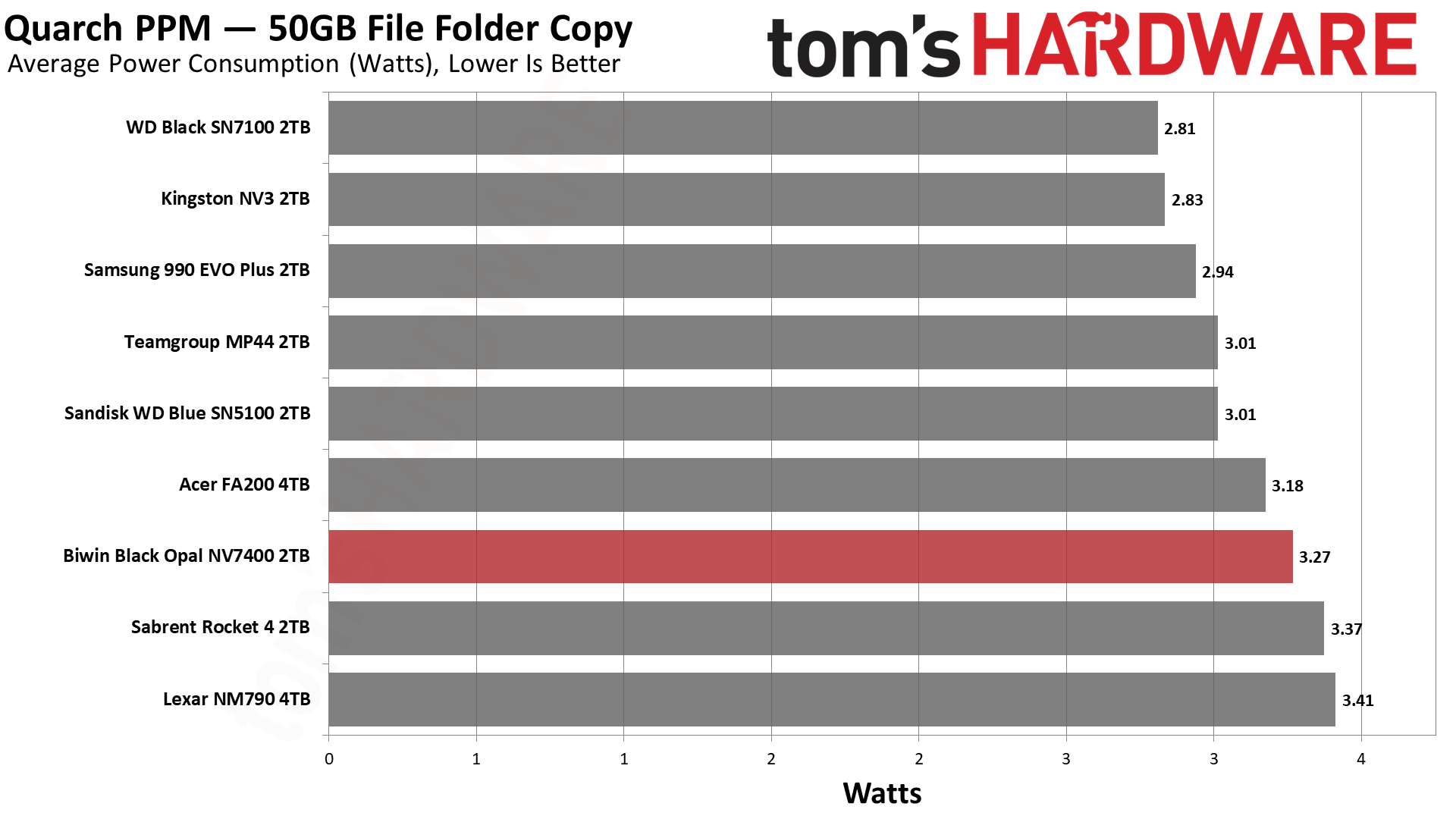

We use the Quarch HD Programmable Power Module to gain a deeper understanding of power characteristics. Idle power consumption is an important aspect to consider, especially if you're looking for a laptop upgrade, as even the best ultrabooks can have mediocre stock storage. Desktops may be more performance-oriented with less support for power-saving features, so we show the worst-case.

Some SSDs can consume watts of power at idle while better-suited ones sip just milliwatts. Average workload power consumption and max consumption are two other aspects of power consumption, but performance-per-watt, or efficiency, is more important. A drive might consume more power during any given workload, but accomplishing a task faster allows the drive to drop into an idle state more quickly, ultimately saving energy.

For temperature recording, we currently poll the drive’s primary composite sensor during testing with a ~22°C ambient. Our testing is rigorous enough to heat the drive to a realistic ceiling temperature.

If there is one place we would expect the NV7400 to dip against some of its peers, it’s with power efficiency. Not because the MAP1602 controller is inefficient – it actually was one of the first really efficient PCIe 4.0 SSD platforms – but because we would expect YMTC’s flash to be more efficient than Micron’s. This is validated by the MP44 being more efficient than the NM7400, but not by a great deal. The NM790 has the excuse of having to drive twice as much flash. On the whole, the NV7400’s power draw, even at peak, is not enough to be concerning. This will work great in any system.

Power consumption also translates to heat production. This drive is single-sided with a simple label, but with four NAND flash packages, it has enough surface area to effectively spread heat. In our testing, it barely got above 50°C and got nowhere near throttling. We think this will not only be fine in any system – including laptops, portable systems, and the PS5 – but will be fine without a heatsink or additional cooling. This includes enclosures, too, and the flash is fast enough to sustain a typical 10Gbps USB connection. That makes it a great drive to have around, even if you don’t have an immediate use in mind.

Test Bench and Testing Notes

CPU | |

Motherboard | |

Memory | |

Graphics | Intel Iris Xe UHD Graphics 770 |

CPU Cooling | |

Case | |

Power Supply | |

OS Storage | |

Operating System |

We use an Alder Lake platform with most background applications such as indexing, Windows updates, and anti-virus disabled in the OS to reduce run-to-run variability. Each SSD is prefilled to 50% capacity and tested as a secondary device. Unless noted, we use active cooling for all SSDs.

Biwin Black Opal NV7400 Bottom Line

The Biwin Black Opal NV7400 is actually not a bad SSD. It has good performance across the stack, its power efficiency is good, and at up to 4TB, there is little to complain about in terms of capacity.

We’ve loved the SSD controller on almost every drive we’ve reviewed with it, but the flash combination is less common. Biwin, or at least those who partner with them, are sometimes associated with YMTC flash – we mean drives like the HP FX700 and Acer Predator GM7 – but actually the NV7400, the Black Opal X570, and the X570 Pro all use Micron flash. We mention this because Micron flash has been tough to get recently, with Micron itself having pulled out of the consumer SSD market. On the other hand, YMTC flash can be politically charged even as it sees increased production. This means things might change in the future, especially with heightened short to medium-term market volatility.

The good news is, this controller is great with a variety of flash. In fact, the Micron TLC on the NV7400 generally performed better than YMTC’s, although we’d consider them comparable in practice. The main thing you have to look out for is a QLC flash swap, which we would not expect for this model, not least because the elevated TBW is almost outside of any expected QLC range.

If you’re looking for a solid drive that isn’t quite high-end, this more than gets the job done. It’s just a matter of finding it at the right price. It’s probably best to jump on it as soon as possible if you want to lock in the storage before conditions worsen. We can easily recommend this drive for just about anything, which should help you sleep better at night if you happen to pick it up.

If we had to give an exception, it would be if you put your foot down on the need for DRAM. The WD Black SN850X – now known as the SanDisk Optimus GX Pro 850X – and others remain solid in that case, but with DRAM prices rising, this can make things even trickier for the very best drives. Most users who demand high performance probably already have good drives or will be looking at PCIe 5.0 ones, like the Samsung 9100 Pro, instead. The reason for this is that the NAND flash takes the greatest share of cost for SSDs, and therefore, the price disparity between PCIe 4.0 and 5.0 drives may start to blur more heavily. This creates a dichotomy where many people will be fine with DRAM-less PCIe 4.0 drives, or they will jump up to a high-end PCIe 5.0 one, leaving the perennial PCIe 4.0 DRAM favorites out of the picture. If that comes to pass, the NV7400 is sitting pretty.

MORE: Best SSDs

MORE: Best External SSDs

MORE: Best SSD for the Steam Deck

- 1

- 2

Current page: Biwin Black Opal NV7400 2TB Performance Results

Prev Page Biwin Black Opal NV7400 Introduction

Shane Downing is a Freelance Reviewer for Tom’s Hardware US, covering consumer storage hardware.