3D XPoint: A Guide To The Future Of Storage-Class Memory

Memory and storage collide with Intel and Micron's new, much-anticipated 3D XPoint technology, but the road has been long and winding. This is a comprehensive guide to its history, its performance, its promise and hype, its future, and its competition.

Storage Or Memory, Or Both?

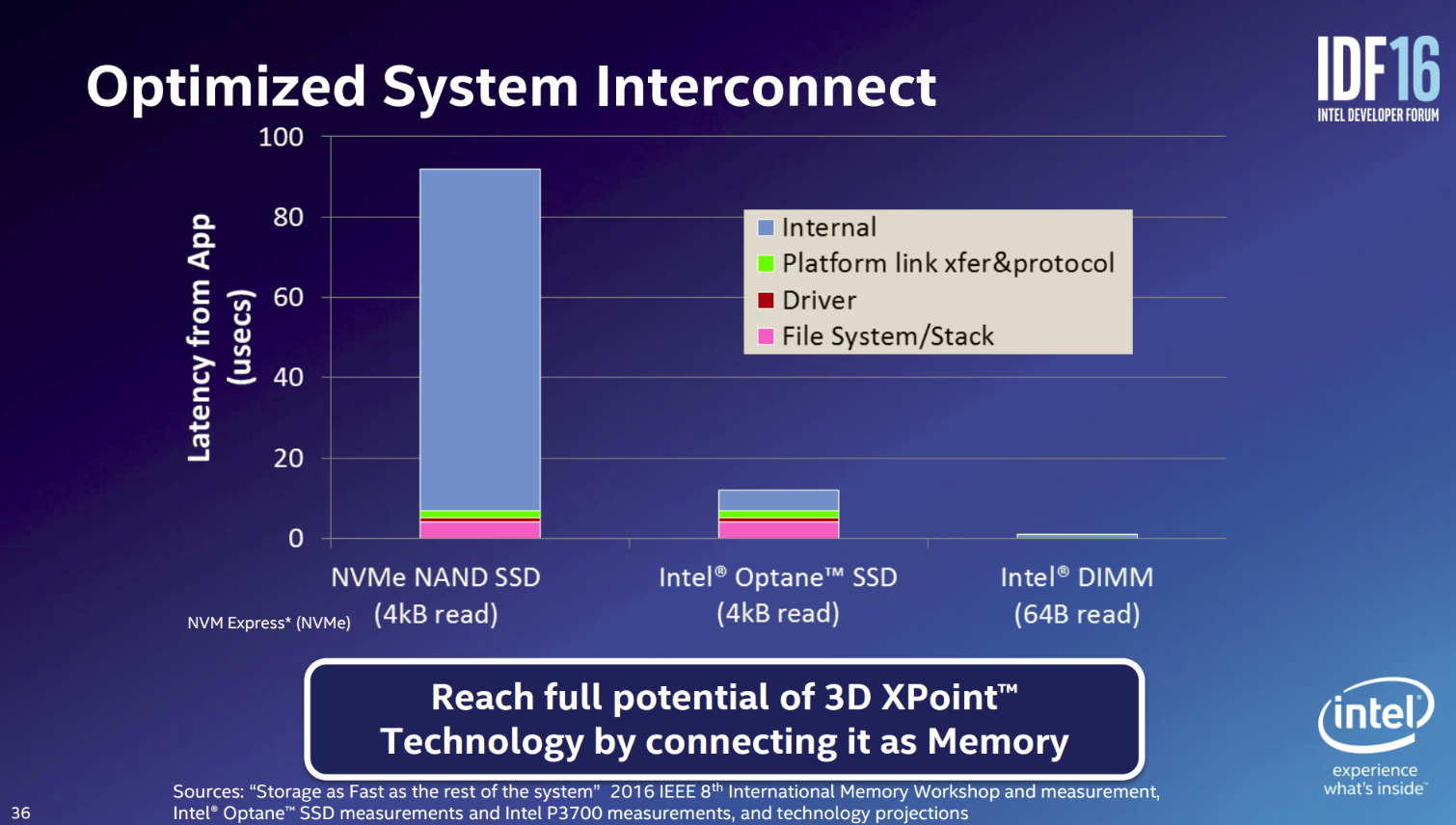

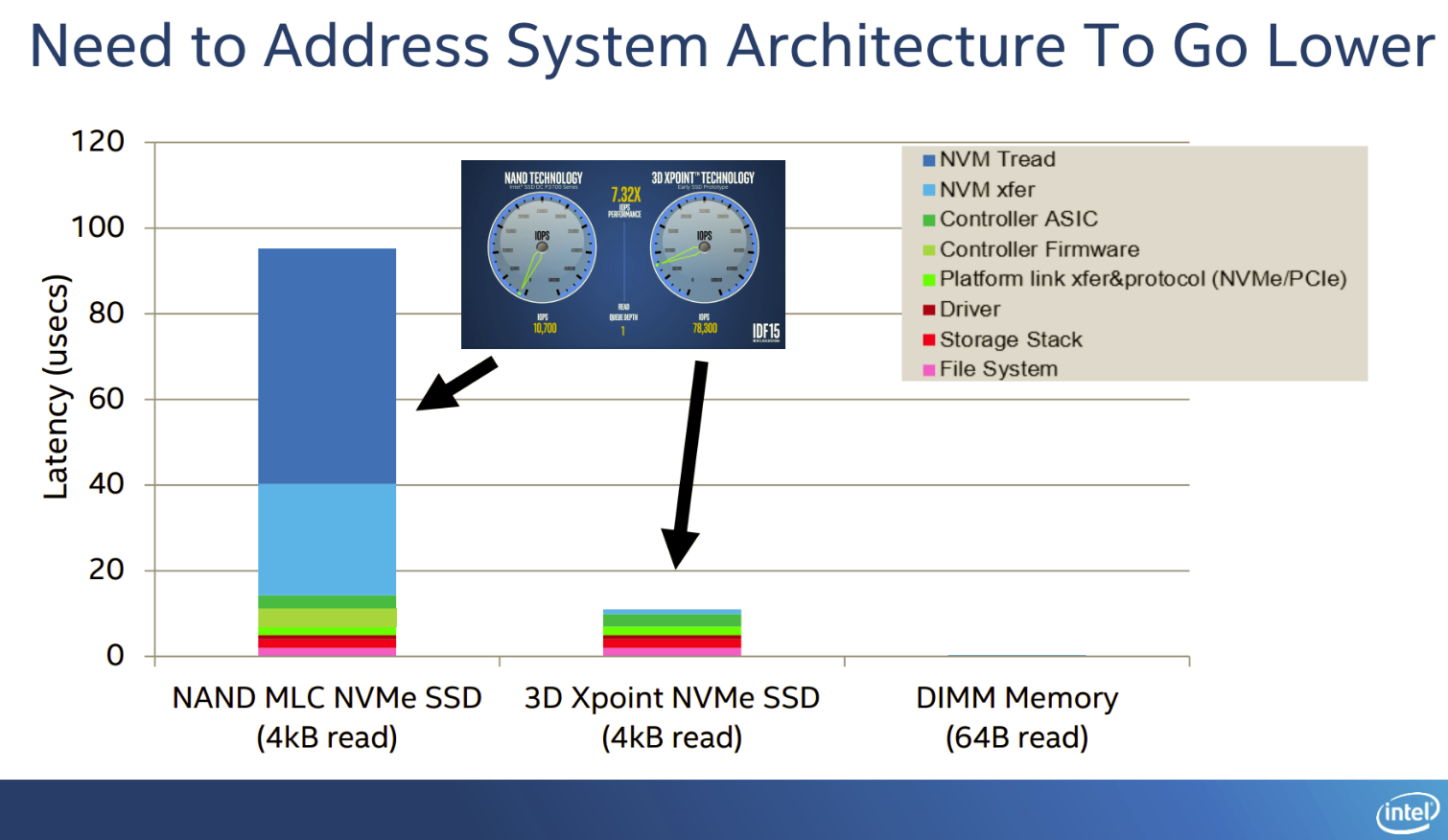

Earlier, we covered how 3D XPoint removes much of the internal device latency associated with accessing NAND storage. The Optimized System Interconnect slide (see slide album below) contains much of the same data, but it also brings the Intel DIMM into the picture, which has almost non-existent platform overhead.

The NVM Tread and NVM xfer, which are the process of reading the NAND media and transferring the data to the SSD controller, respectively, are almost completely removed within a 3D XPoint SSD. The new non-ONFI media interface also helps deliver that performance to the controller faster. The remaining overhead comes from the controller ASIC (ECC, etc.) and firmware (wear leveling, GC, etc.). 3D XPoint largely reduces those problems, but the platform "link xfer&protocol" (NVMe), driver, storage stack, and file system still stand in the way.

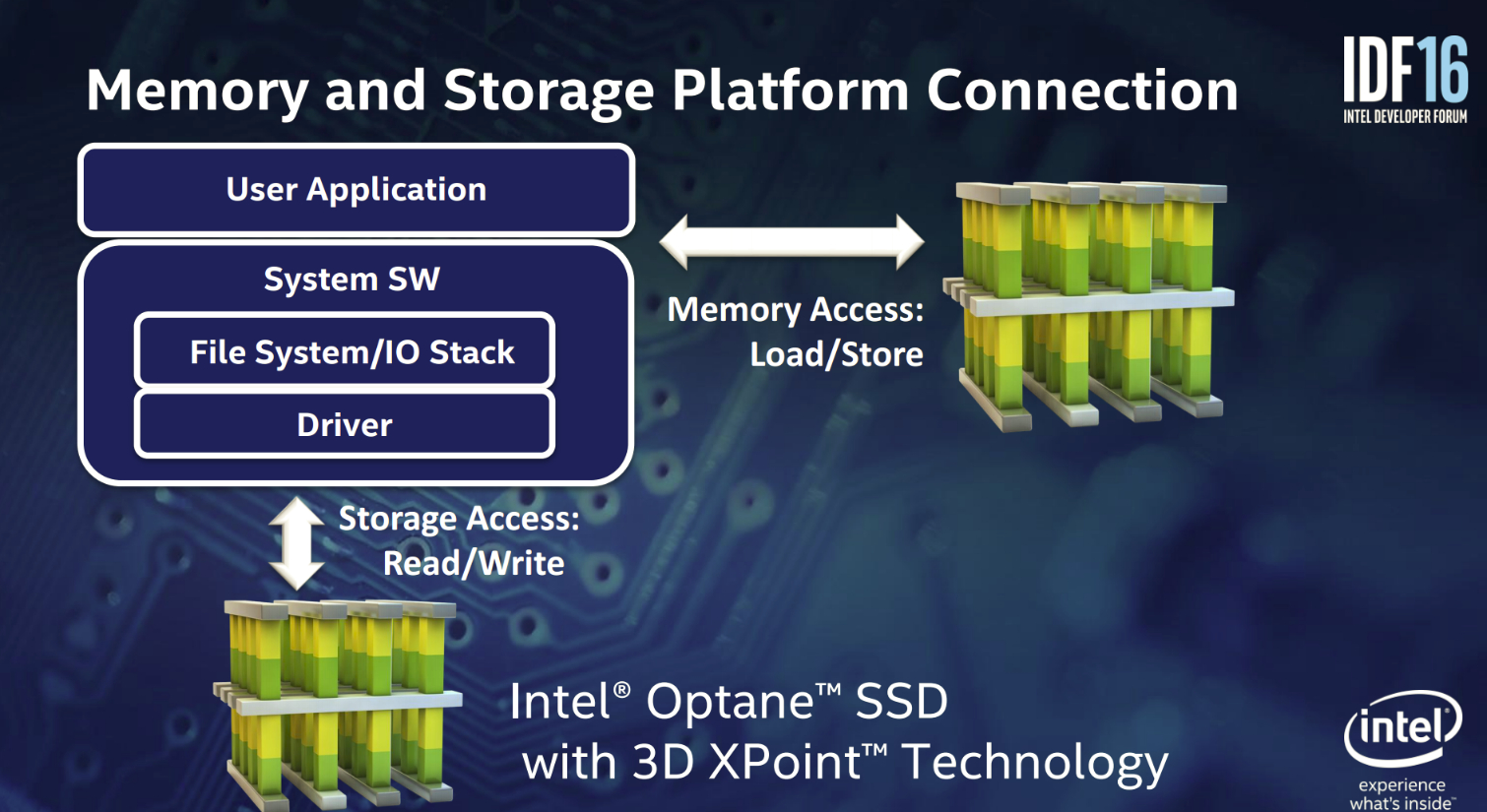

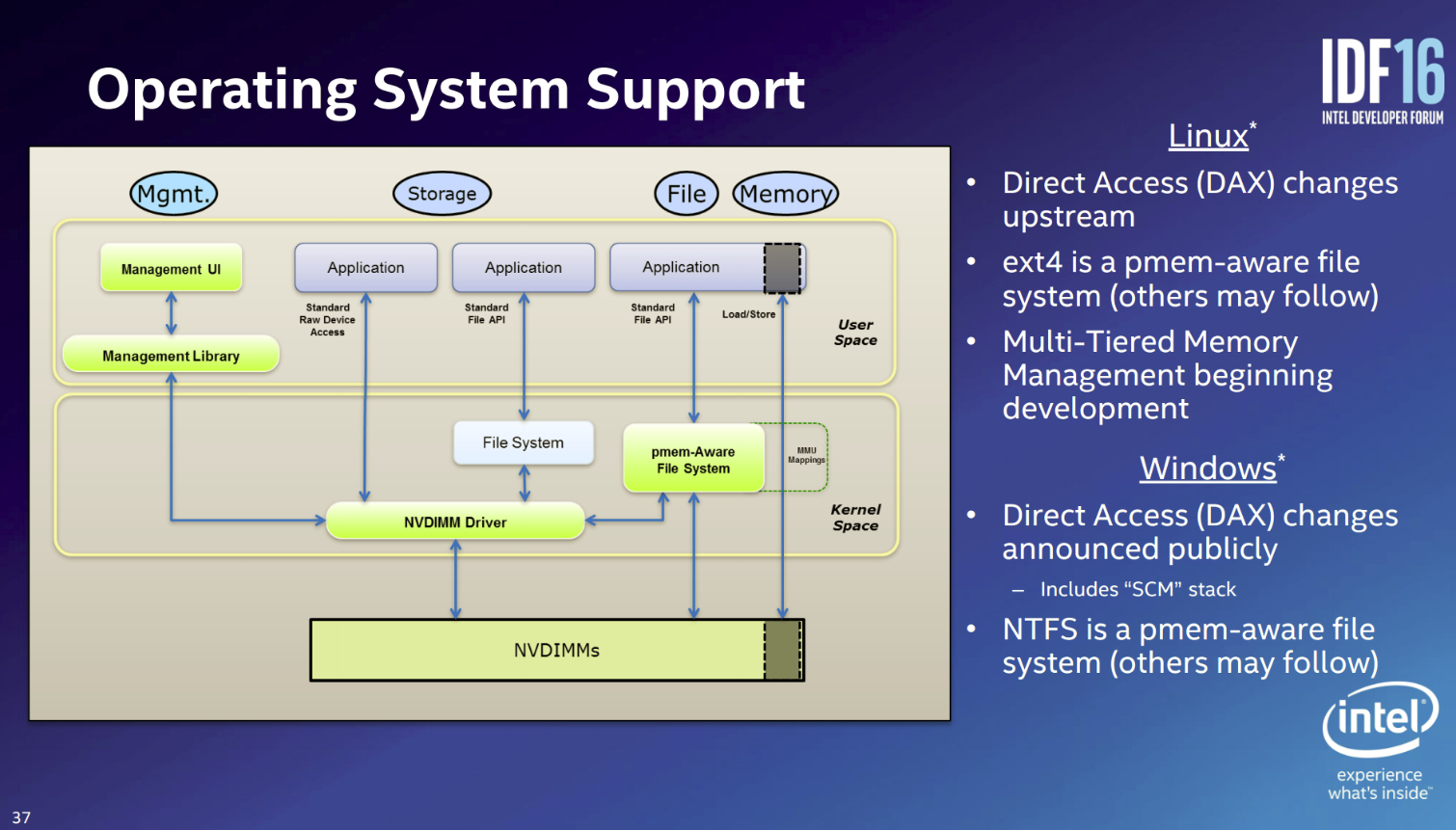

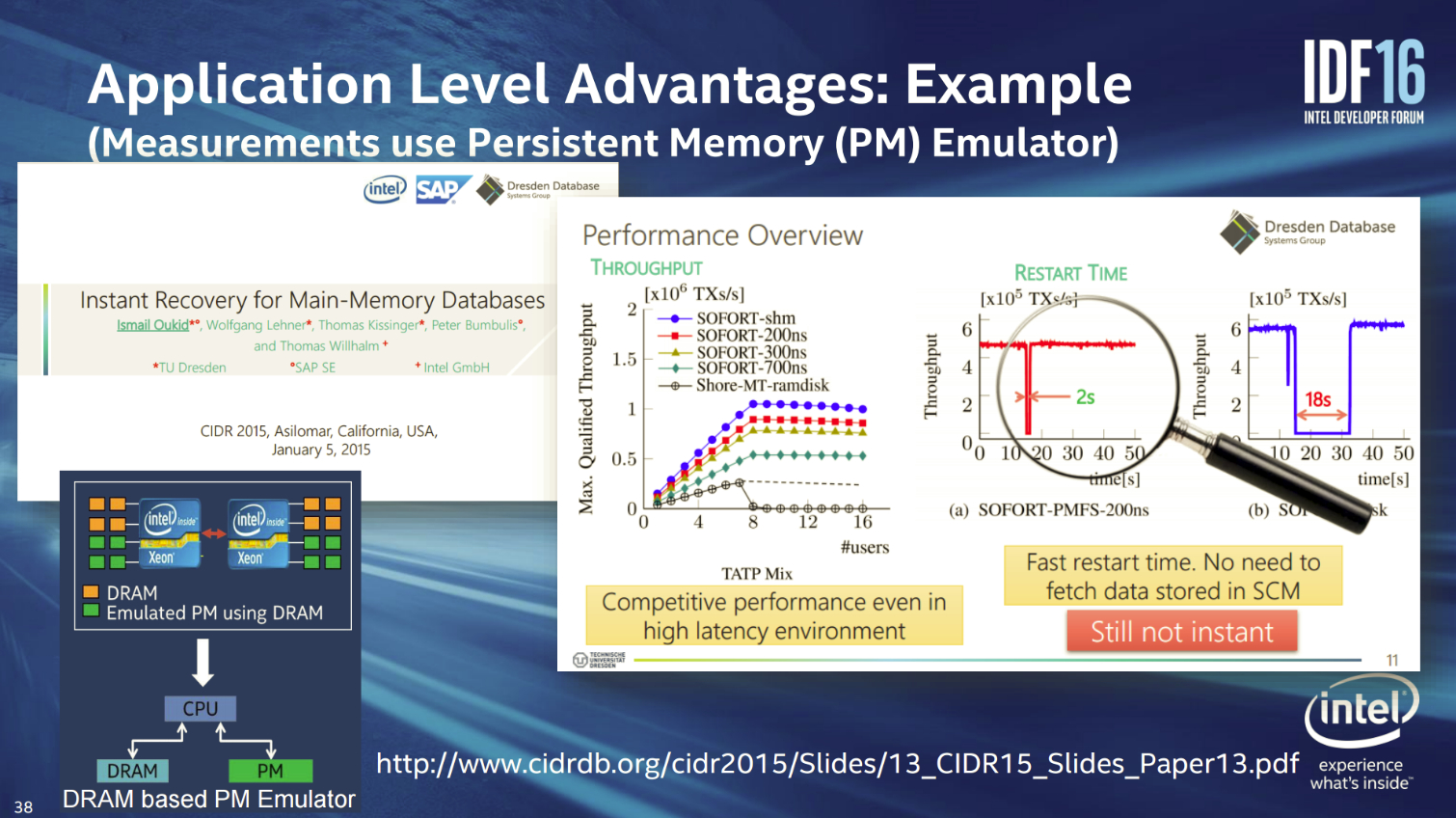

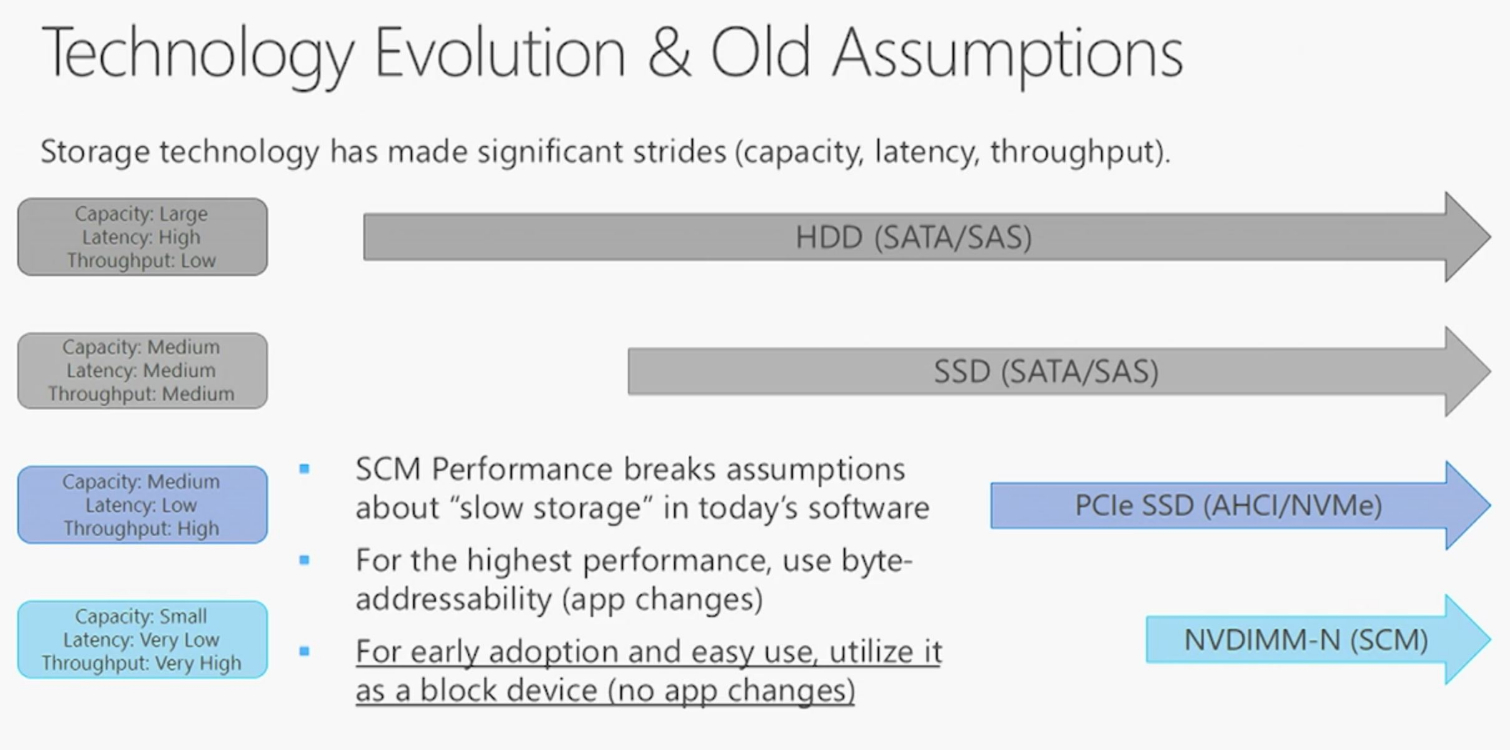

Removing these last obstacles will unlock 3D XPoint's full capabilities. One of the key differentiators between memory and storage access is how the system accesses data. Storage access requires the comparatively slow read/write commands that must traverse the driver and stack to get to the application, whereas memory uses load/store commands that have a faster path to the application, which results in the elimination of the additional overhead.

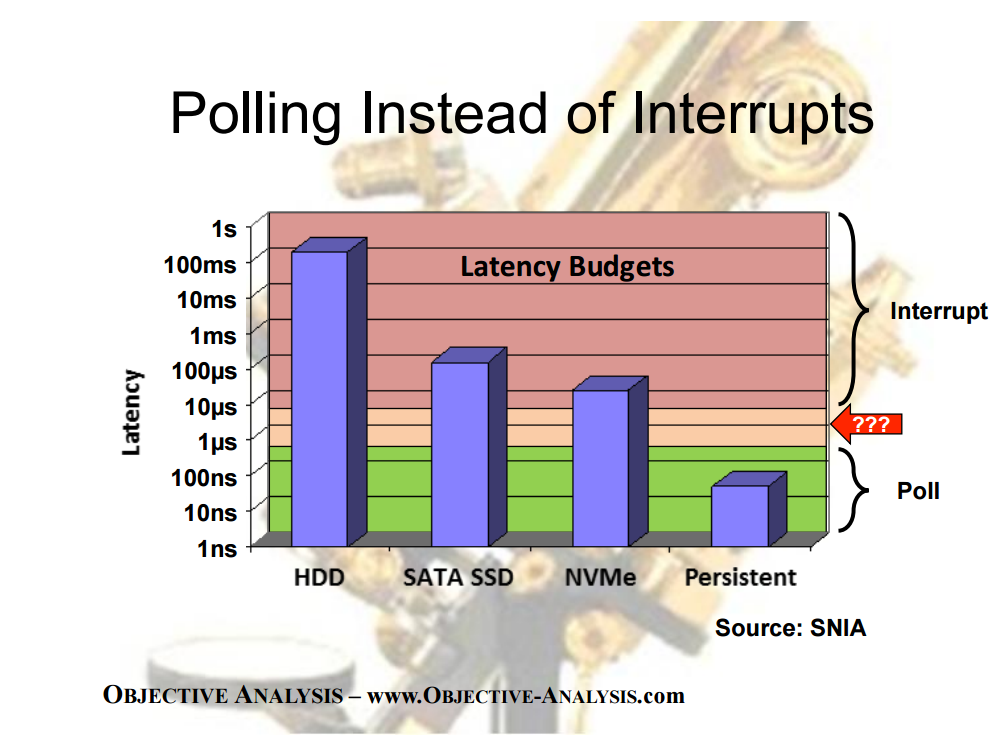

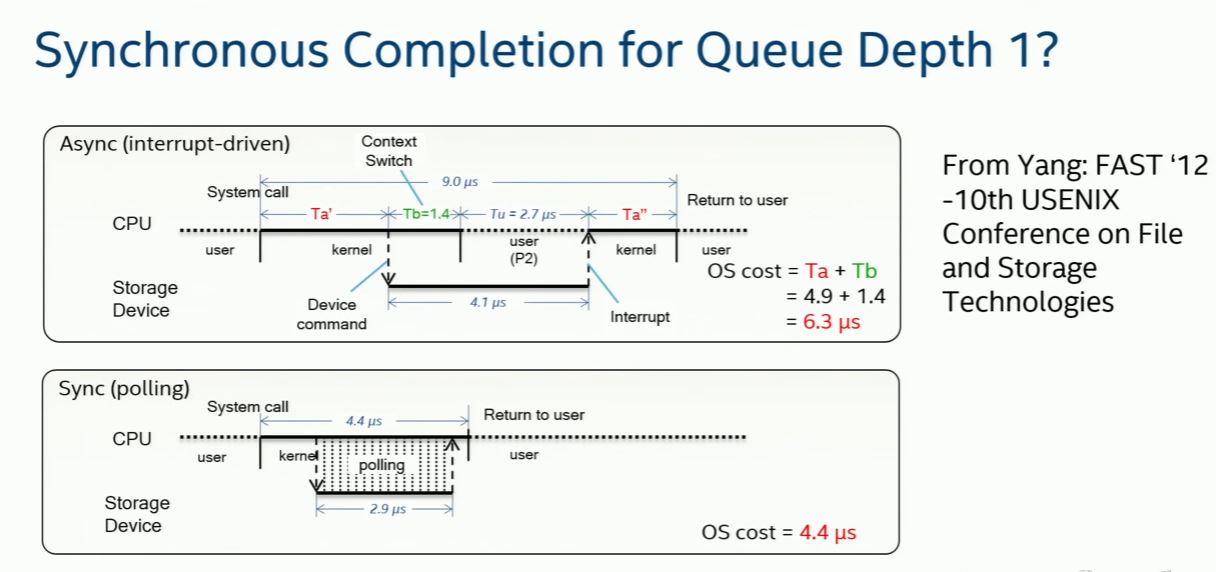

Usually, storage semantics require interrupts, but there is a growing movement to use polling instead. Polling simply checks for outstanding requests on a regular cadence, as opposed to waiting for an interrupt to begin processing. It requires 6.9 microseconds of OS time to issue and receive an interrupt, whereas it only requires 4.4 microseconds for polling. Polling is an emerging technique to boost low-QD performance, but it does come at a significant CPU expense. Intel already has polling provisions in its SPDK (Storage Performance Development Kit), so we expect it to become more commonplace, particularly with persistent memories. There are also Linux developments that only poll when the queue is active, which should help reduce overhead.

The Support Ecosystem

Intel is bringing its 3D XPoint DIMMs to market, and though the silence around them has fostered suspicions of a delay, the persistent memory ecosystem development continues unabated. We don't know if Intel will use NVDIMM approaches, or simply use its DIMMs as a standard memory replacement, or both.

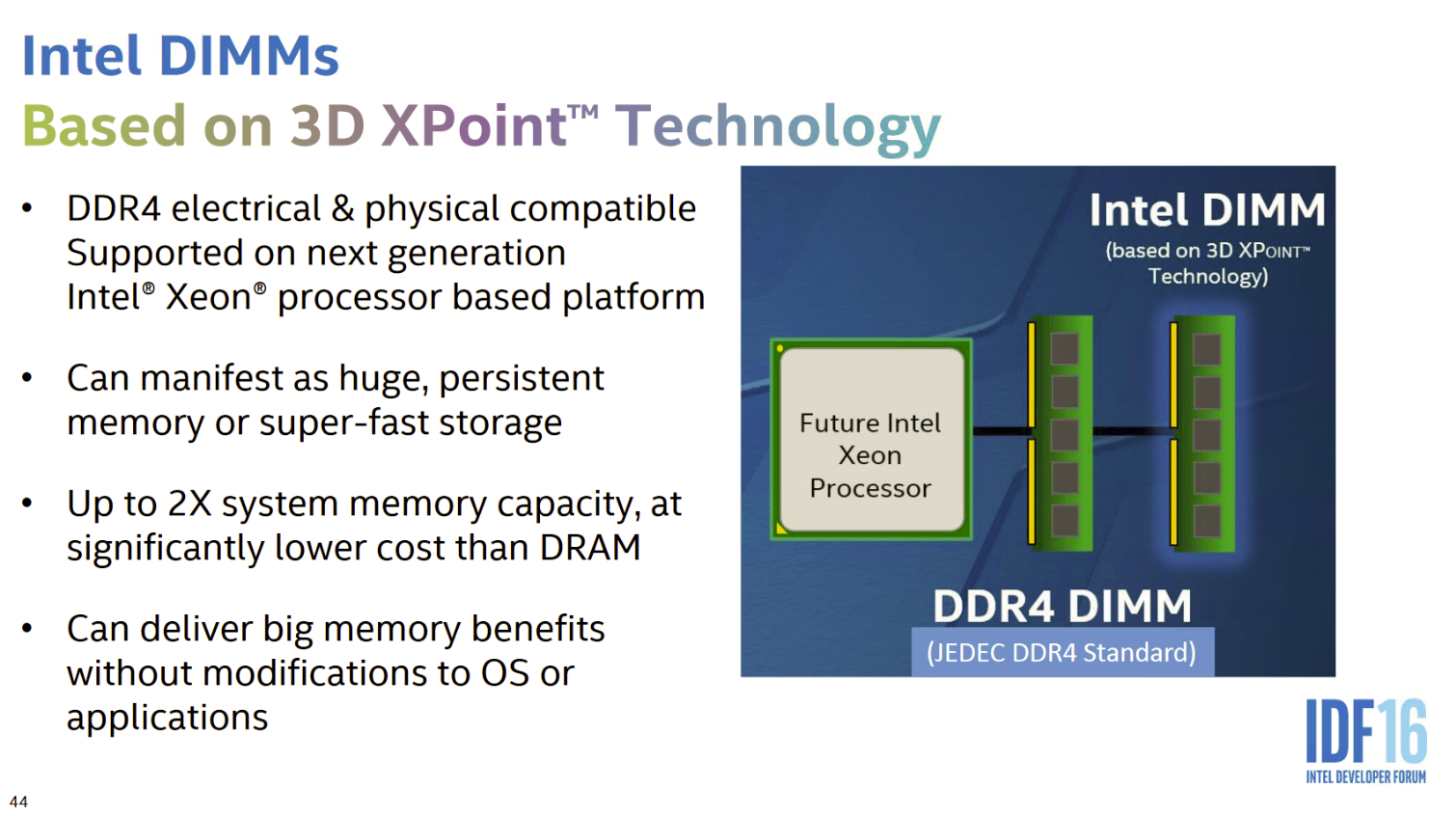

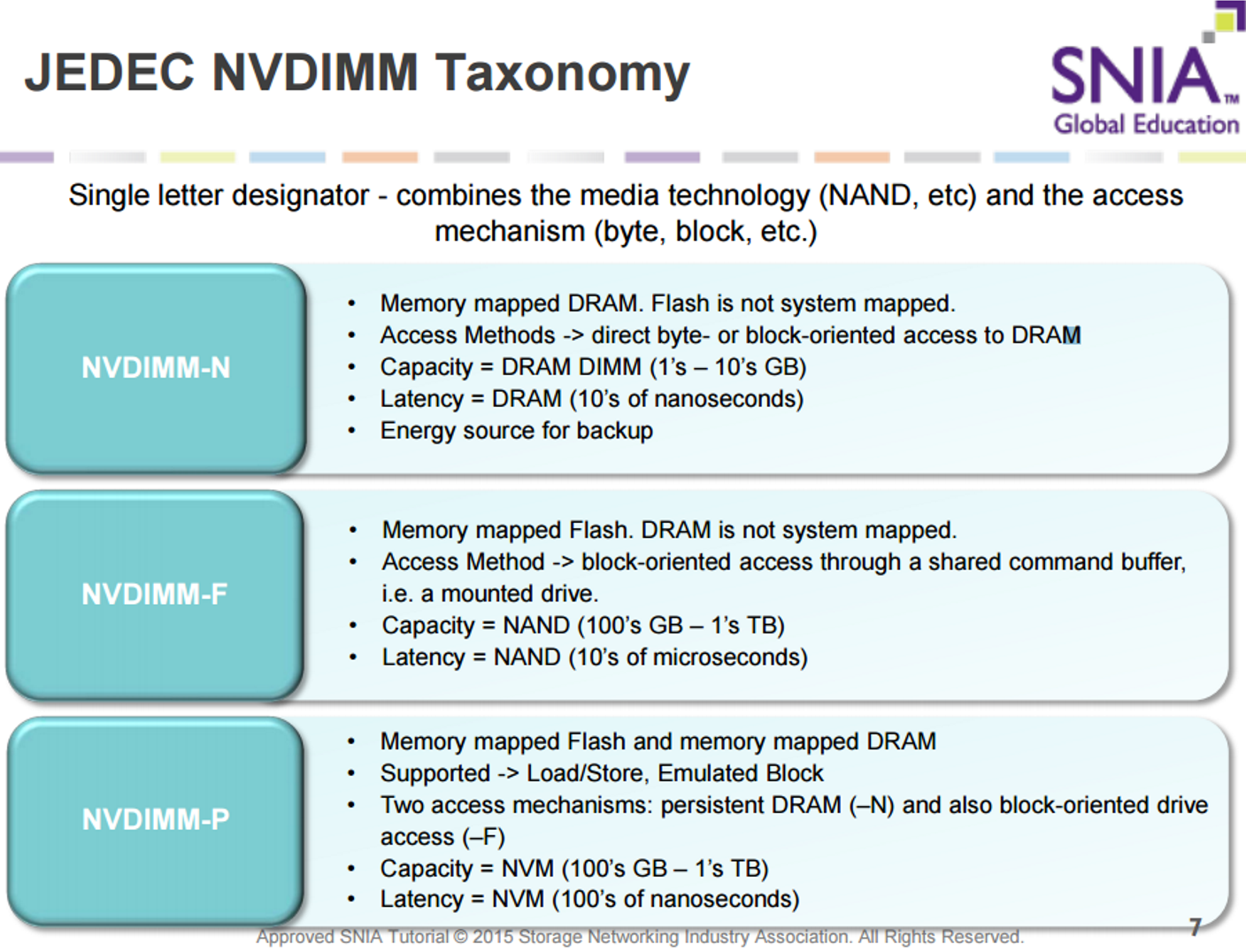

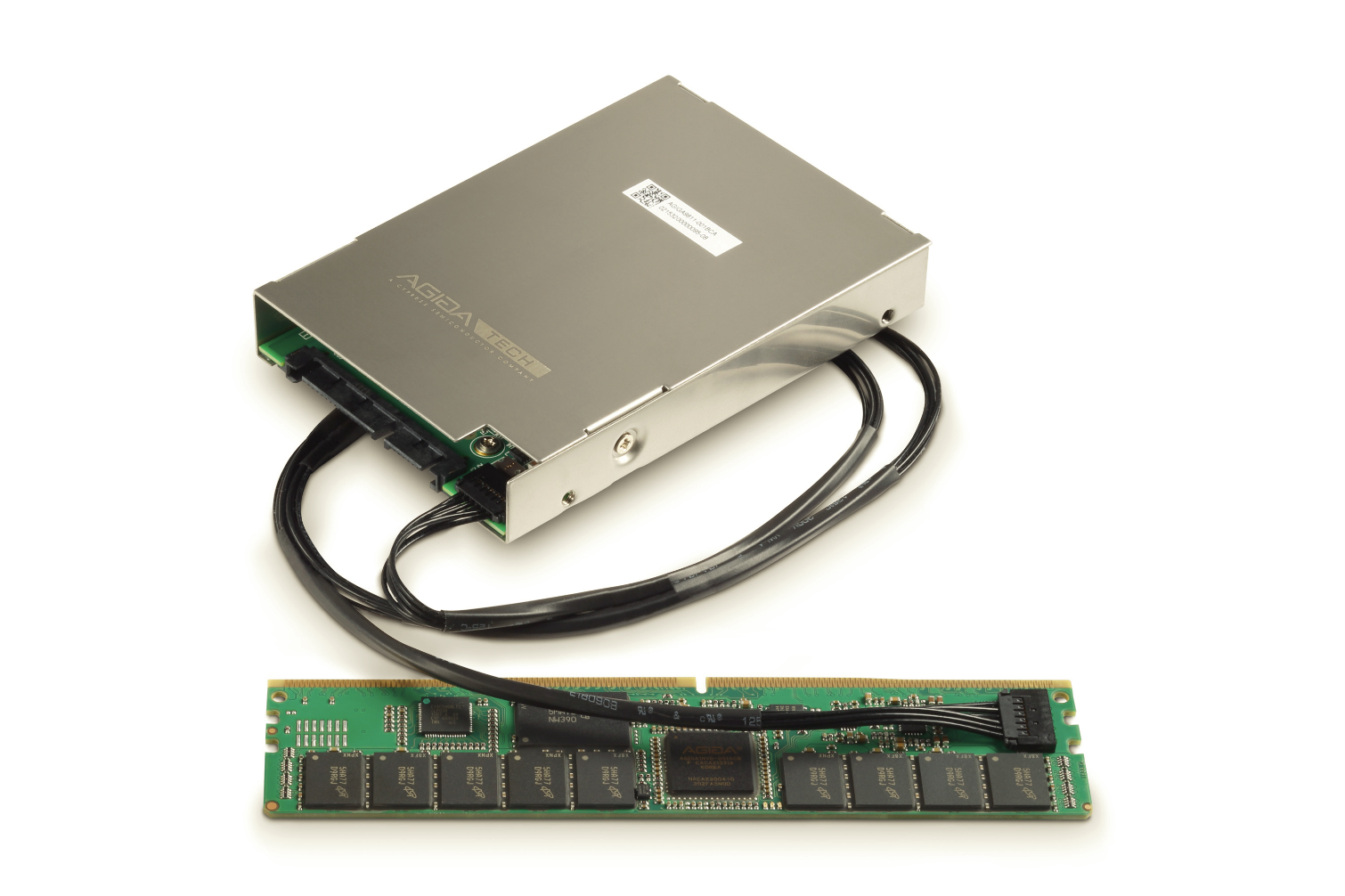

Vendors can use either the PCIe bus or DIMM slots to employ 3D XPoint as either memory or storage, with the DIMM slot being the most desirable option due to its faster interface. In-memory compute has roared to the forefront, and the industry is already developing NVDIMM technology with NAND-based DIMMs. NVDIMMs (Non-Volatile DIMM) are electrically and physically DDR4-compatible DIMMs that support either storage or persistent memory use cases with NAND. 3D XPoint could serve the same purpose, but with more speed. Using NVDIMMs requires some manipulation of the existing stack, which is already well underway.

NVDIMMs come in many flavors. Some use a non-volatile memory to back volatile DRAM (byte- or block-addressable NVDIMM-N), address NAND flash (or other non-volatile memories) as block-accessed memory (NVDIMM-F), or address both DRAM and NAND as a combined memory pool for either persistent DRAM or block access (NVDIMM-P).

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

There are a number of companies working on blended software-defined memory (SDM) initiatives that unlock a new wave of combined memory and storage pools. Plexistor is top of mind, largely because Micron announced during the Flash Memory Summit that it is working with the company. There are also other techniques, like Diablo's Memory1, that simply use NAND as the primary memory pool.

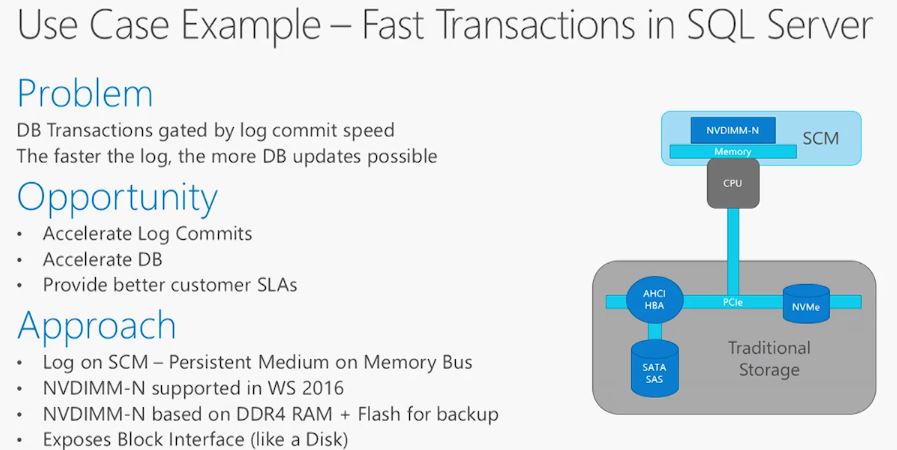

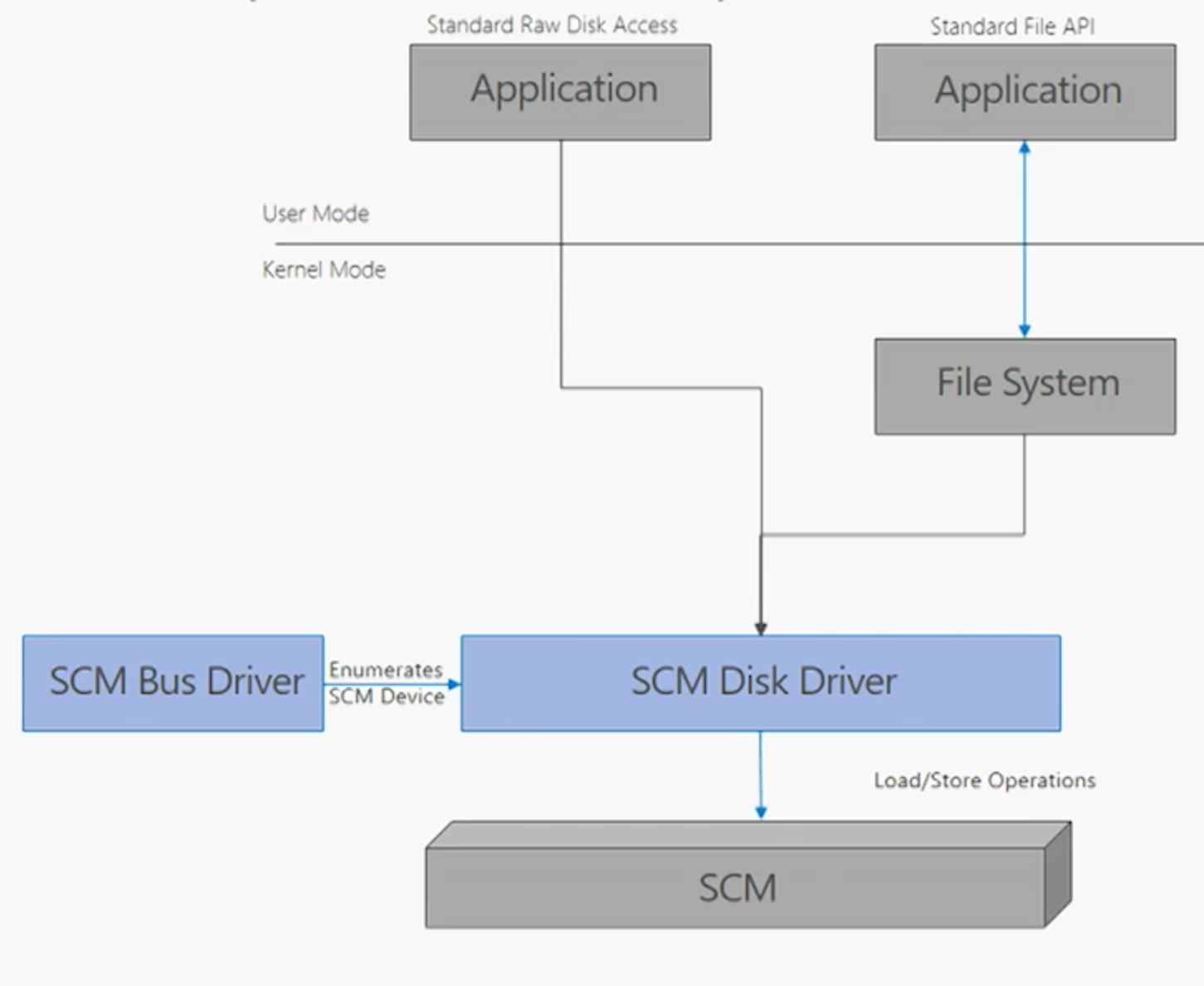

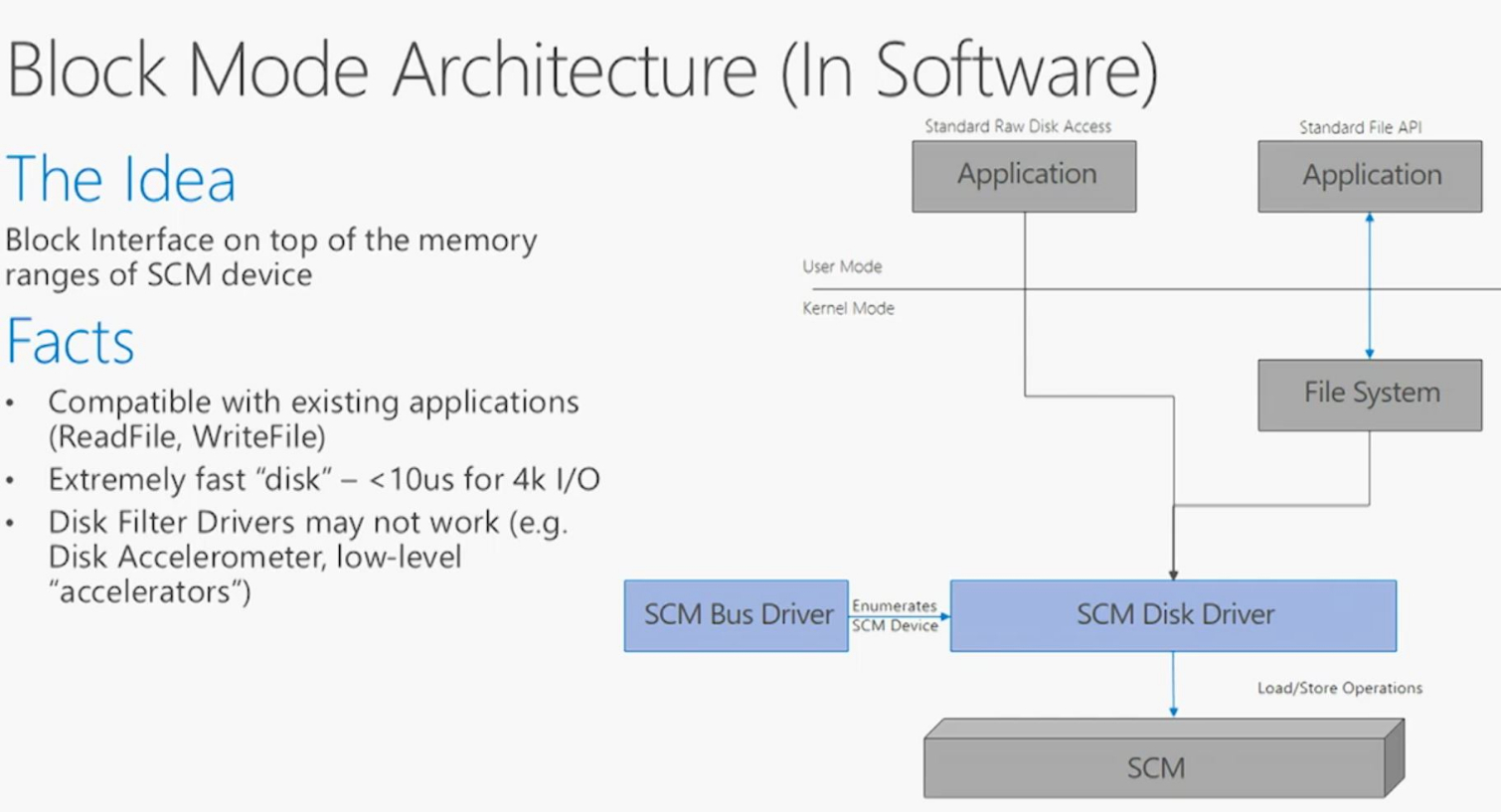

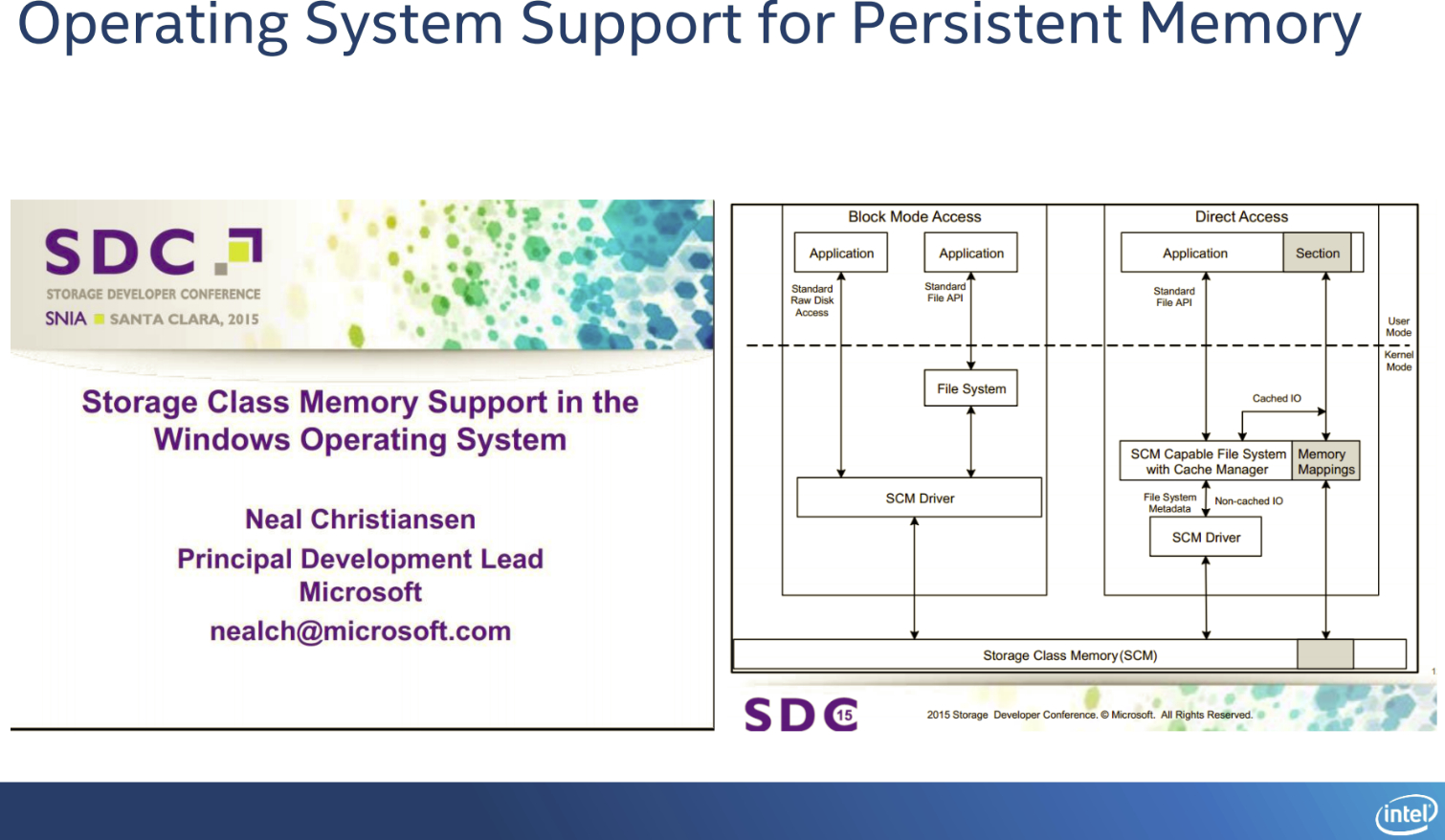

Microsoft Dances An NVDIMM-N Jig

Much of the leading-edge work for persistent memory programming is still underway, but NVDIMMs have already hit prime time. Windows Server 2016 and a forthcoming Windows 10 build provide for using NVMDIMM-N either as block storage (with no app changes) or as Direct Access volumes (DAX) for byte-addressable, memory-mapped use cases. Microsoft even baked the functionality into Storage Spaces, which simplifies and expands use cases and allows for common management tasks like volume mirroring, striping, and write-back caching with NTFS and ReFS file systems.

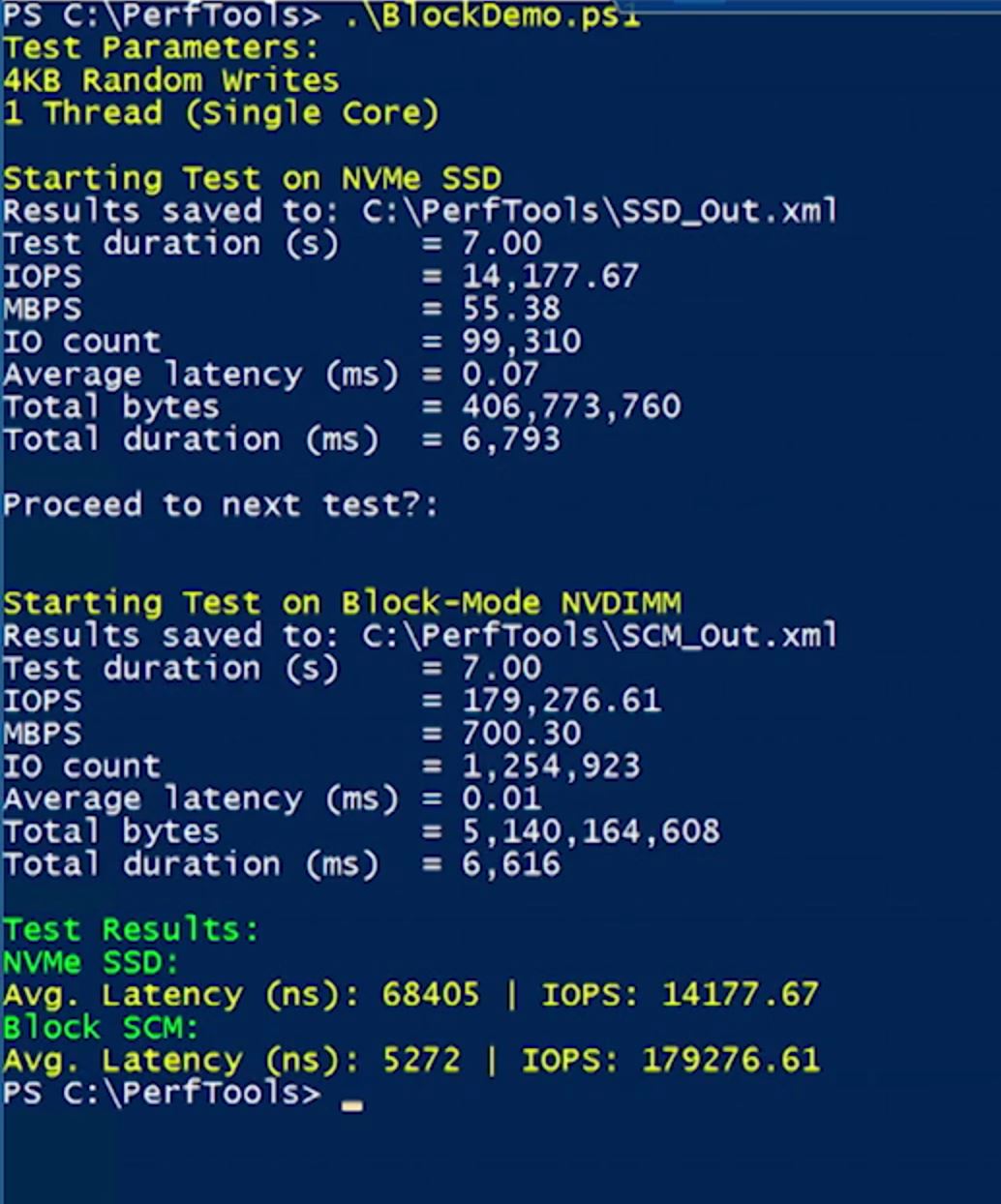

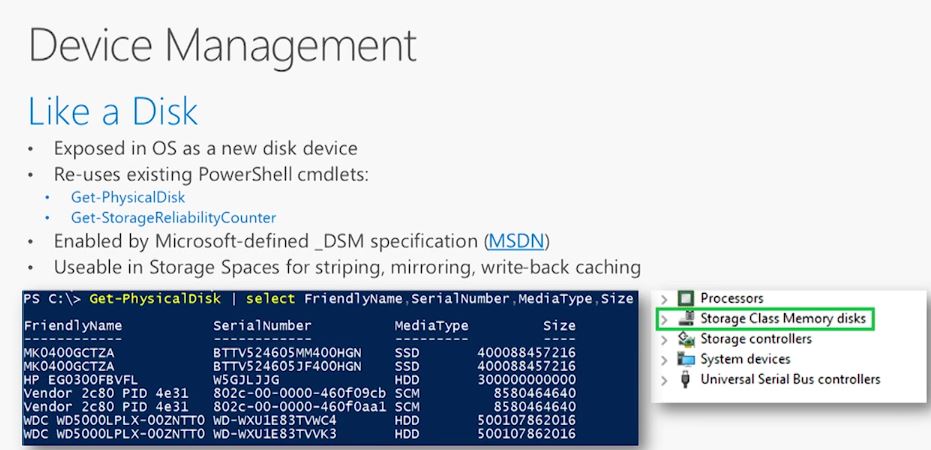

The OS abstracts away the complexity and speaks to the underlying media with standard memory semantics, such as load/store and memcopies. Microsoft provided a demo of an NVMe SSD at QD1 compared to an NVDIMM-N block device. The SSD scores 14,177 IOPS at QD1 compared to 179,276 IOPS for the NVDIMM. Another interesting caveat is the new "Storage Class Memory disks" entry in the Device Management pane, which we can't wait to see on our own computers.

Proprietary Interconnects Go Big

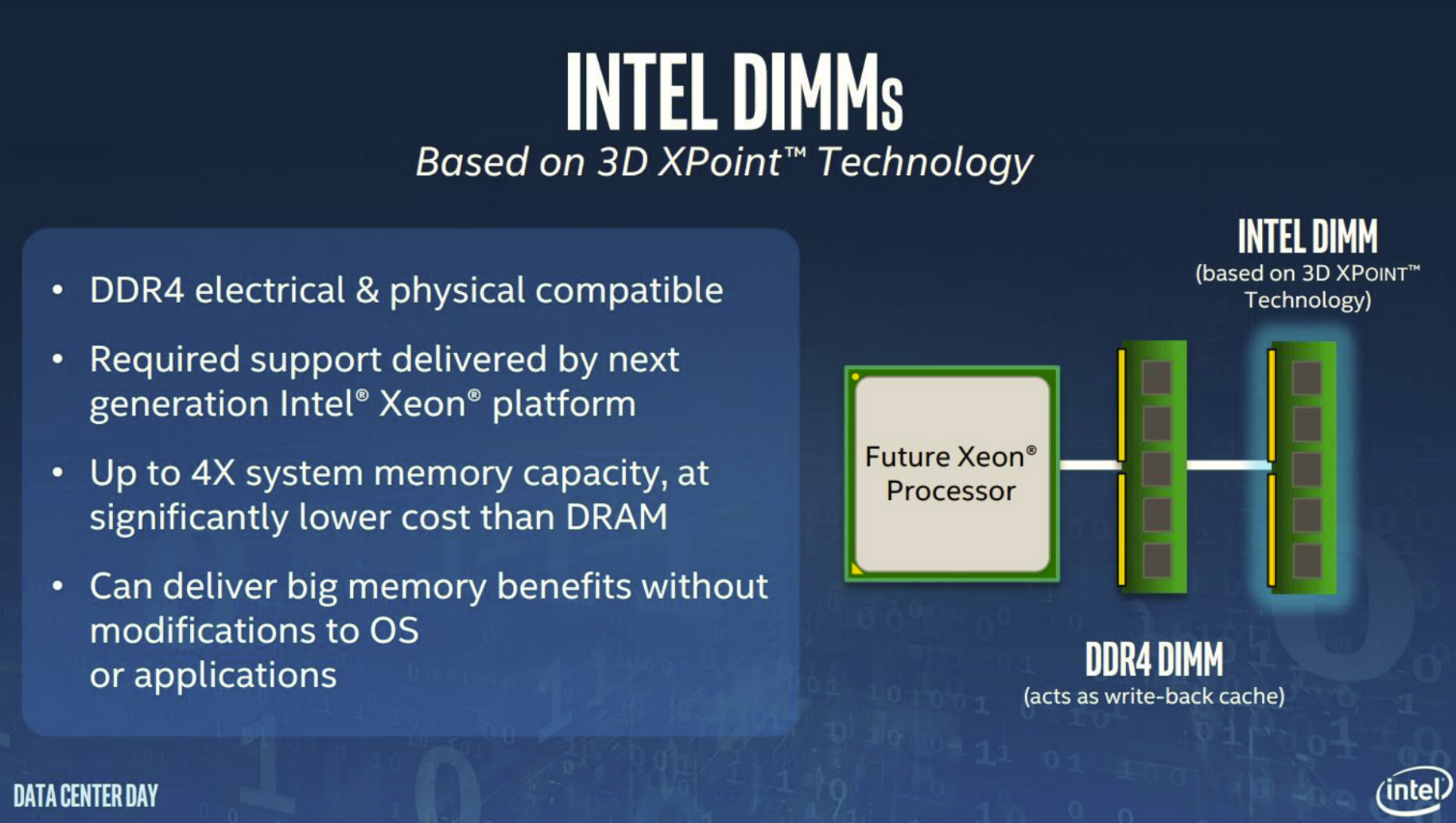

Intel's Optane DIMM strategy is to use 3D XPoint as its own flavor of memory, which will bring the benefit of increased density. Intel disclosed that this would require proprietary extensions to the DDR4 interface due to the long "outliers," or delayed responses, that are inherent to any non-volatile storage medium. For instance, a read or write command may not process in the nice orderly fashion that the DDR4 interface requires based on an ECC event.

The DDR4 spec requires a fixed number of clock cycles for data to return, and it doesn't have provisions to accept commands with variable latency. Intel's proprietary DDR4 extensions will accommodate the need. Intel has noted that the DIMMs will require processor support, which is likely the result of some adjustments to the IMC (Integrated Memory Controller) to accommodate the new extensions.

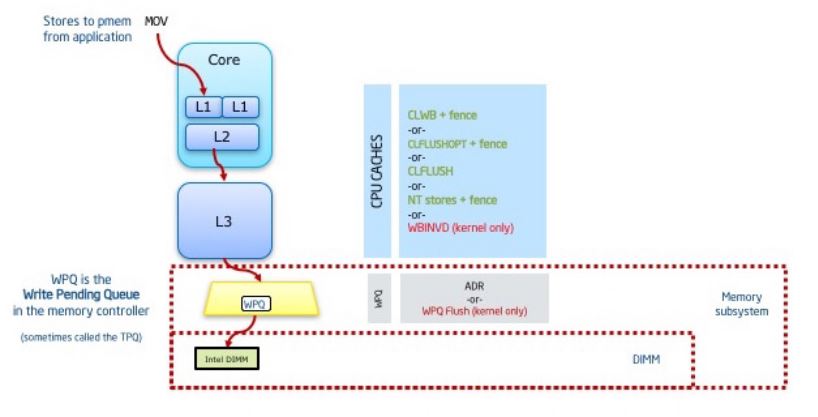

The memory system is a complex tiered model of L1, L2, L3, and other volatile caches, so ensuring that data written to persistent memory is in a non-volatile location becomes a critical requirement. The operating system and applications have to be aware of the location of data and have the ability to steer it to the correct location.

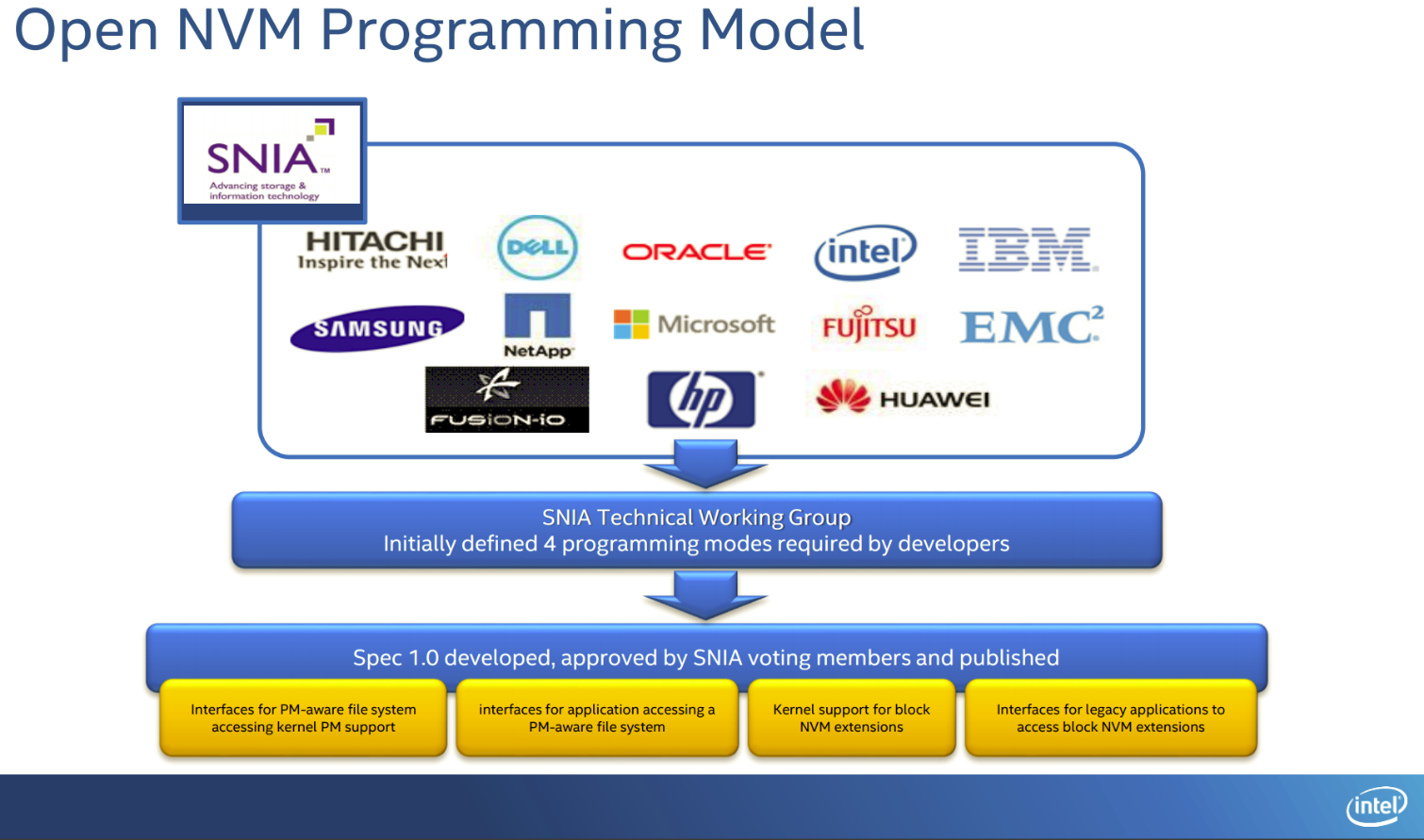

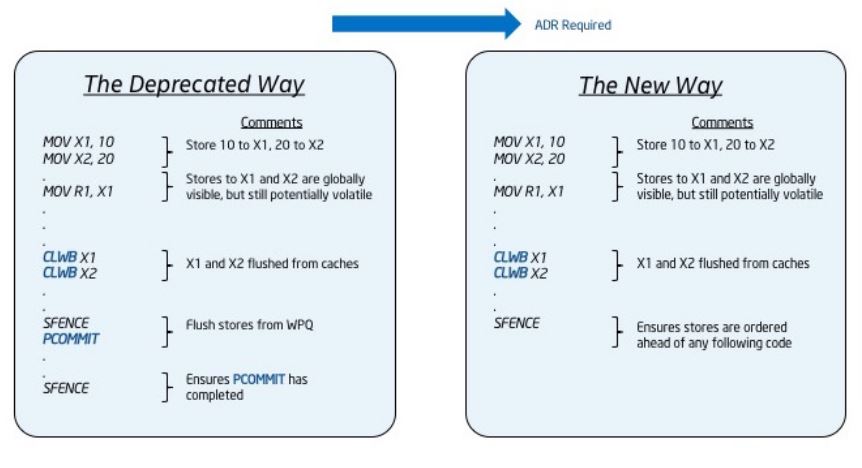

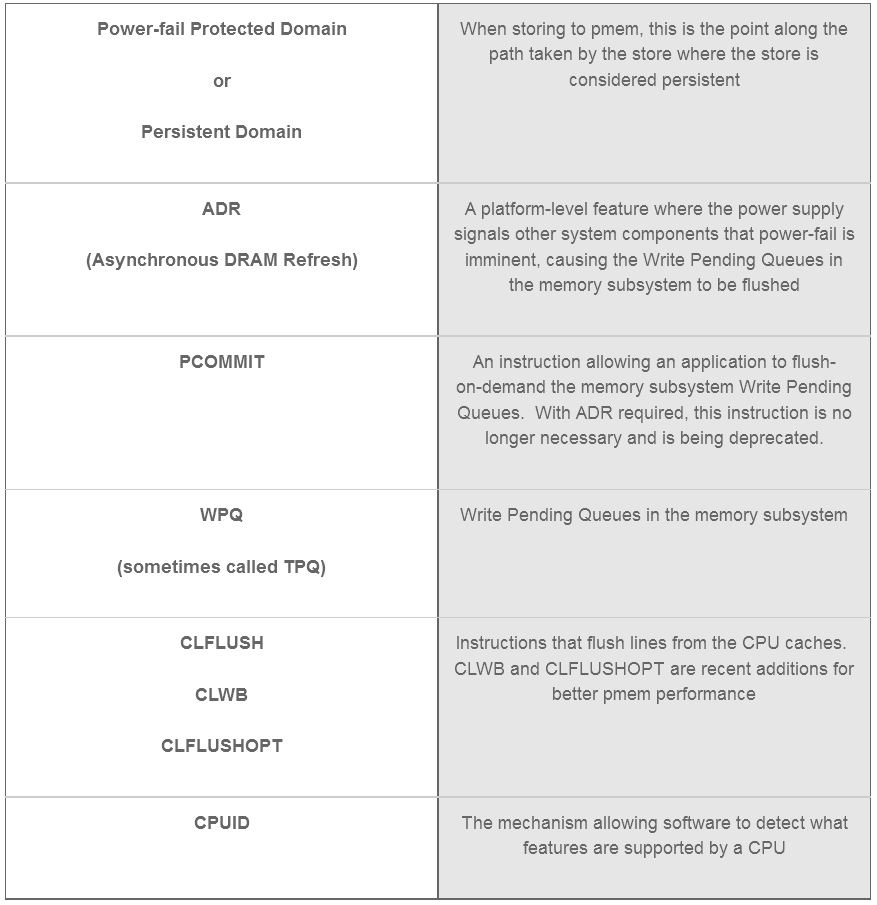

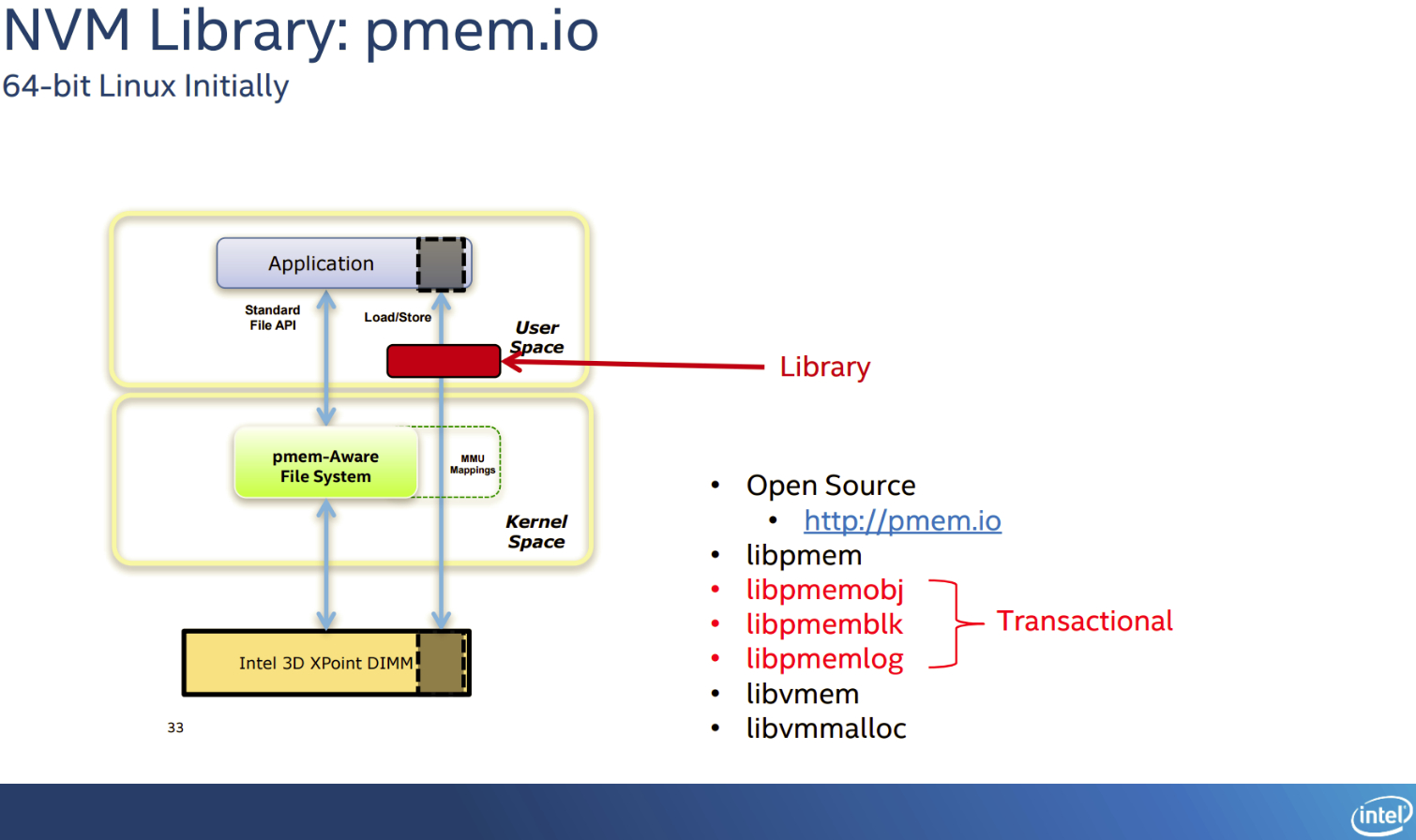

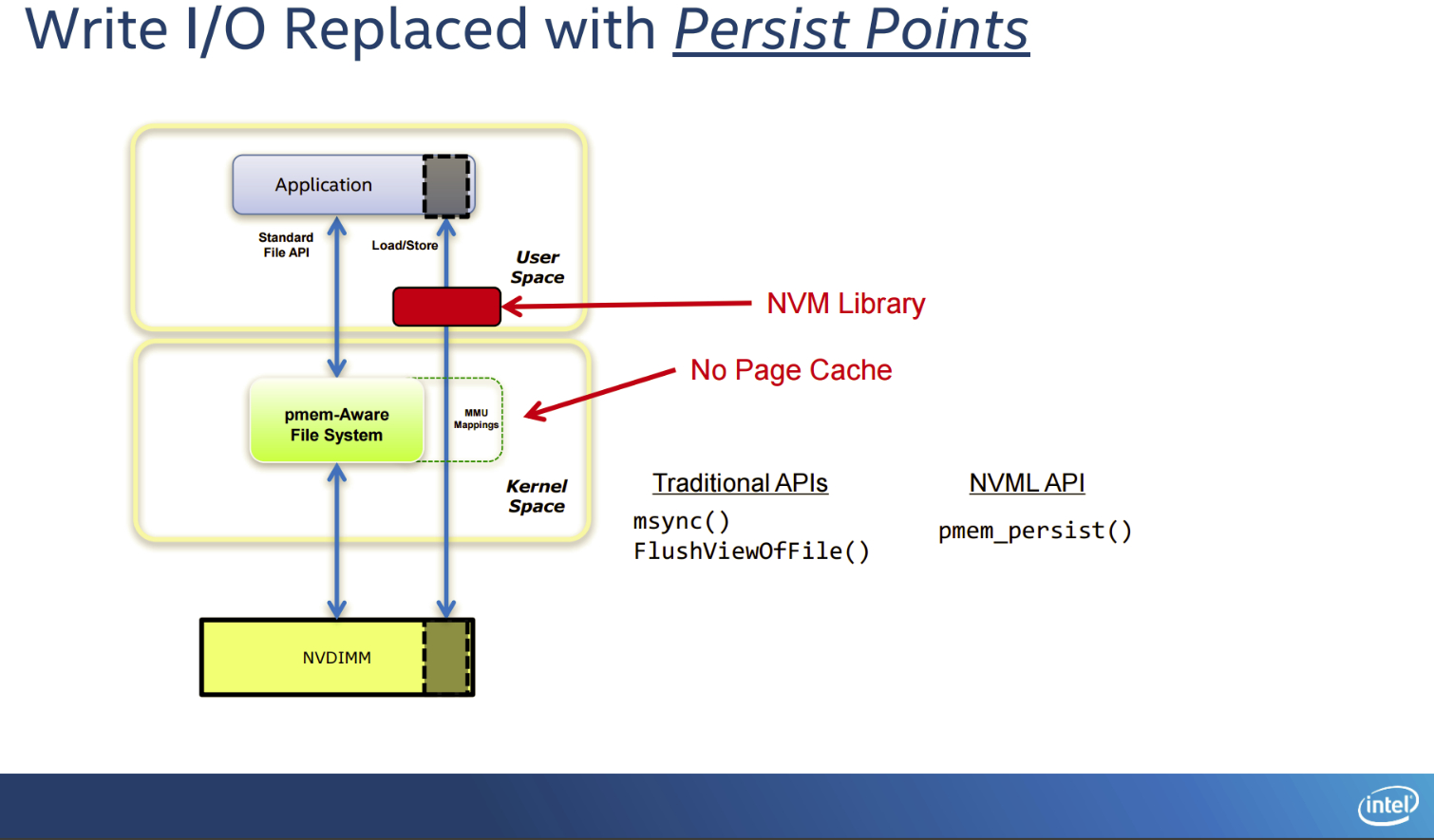

The SNIA Open NVM programming model, which consists of multiple industry partners and covers Linux and Windows, has defined new libraries with x86 instructions designed to speed access and ensure that the "persisted" data is committed to the non-volatile portion of the memory hierarchy (the persistent memory DIMMs). The Linux pmem.io set of NVM libraries allows for using memory-mapped persistent memories, which communicate with the file system using load/store commands to increase performance with the same storage medium (such as NAND) by removing the storage-centric read/write push/get storage commands.

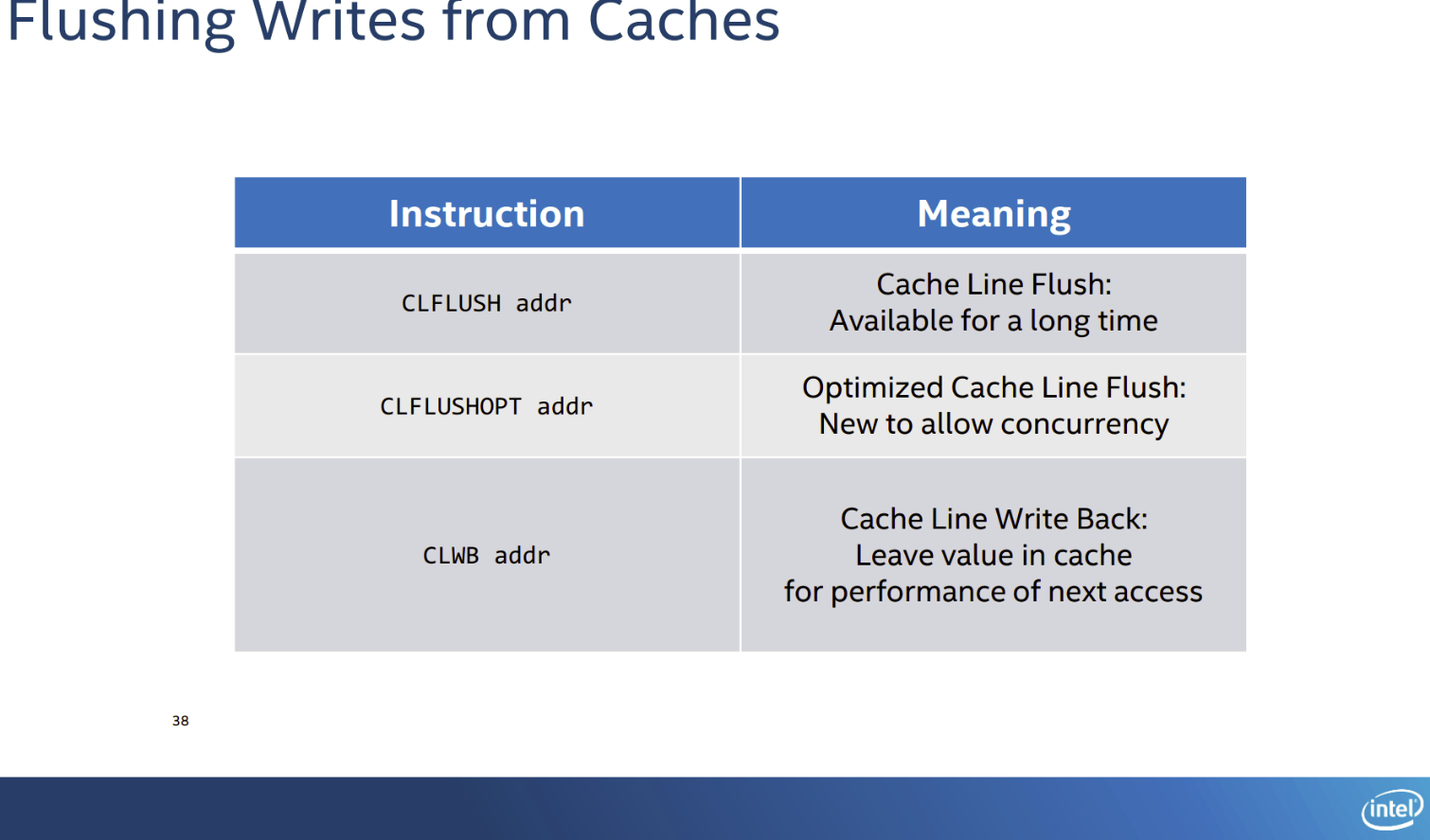

The Windows model defines new cache and memory management instructions such as CLFLUSHOPT (Optimized Cache Line Flush) and CLWB (Cache Line Write-Back) to supplement CLFLUSH (Cache-Line Flush). The instructions manage and ensure data flushes. These software approaches apply to either persistent NVDIMM or standard persistent DIMM uses.

However, this is a fast-moving space. The pcommitt command, which was a key portion of the strategy and one of the early signs that new persistent memories were on the horizon, was recently deprecated with little notice. There will likely be more changes as the industry hammers out the final specifications.

The initial indicators appear to suggest that 3D XPoint's endurance might not be suitable for use as a pure memory replacement, but there are ways to mitigate the lower endurance. Optane DIMMs could work in numerous ways, including with DDR4 used as a fast front-end cache for vast 3D XPoint memory pools (managed by the IMC), or even hybrid DIMMS with both DDR4 and 3D XPoint together. In either case, Intel's DIMMs may have hit a roadblock, but there is always the option to merely use the first-gen 3D XPoint with existing NVDIMM technology if endurance and thermals are concerns.

MORE: Best Enterprise SSDs

Current page: Storage Or Memory, Or Both?

Prev Page Enthusiast, Workstation, Data Center Performance Next Page The Economics And Competition

Paul Alcorn is the Editor-in-Chief for Tom's Hardware US. He also writes news and reviews on CPUs, storage, and enterprise hardware.

-

coolitic the 3 months for data center and 1 year for consumer nand is an old statistic, and even then it's supposed to apply to drives that have surpassed their endurance rating.Reply -

Paul Alcorn Reply18916331 said:the 3 months for data center and 1 year for consumer nand is an old statistic, and even then it's supposed to apply to drives that have surpassed their endurance rating.

Yes, that is data retention after the endurance rating is expired, and it is also contingent upon the temperature that the SSD was used at, and the temp during the power-off storage window (40C enterprise, 30C Client). These are the basic rules by which retention is measured (the definition of SSD data retention, as it were), but admittedly, most readers will not know the nitty gritty details.

However, I was unaware that JEDEC specification for data retention has changed, do you have a source for the new JEDEC specification?

-

stairmand Replacing RAM with a permanent storage would simply revolutionise computing. No more loading an OS, no more booting, no loading data, instant searches of your entire PC for any type of data, no paging. Could easily be the biggest advance in 30 years.Reply -

InvalidError Reply

You don't need X-point to do that: since Windows 95 and ATX, you can simply put your PC in Standby. I haven't had to reboot my PC more often than every couple of months for updates in ~20 years.18917236 said:Replacing RAM with a permanent storage would simply revolutionise computing. No more loading an OS, no more booting, no loading data

-

Kewlx25 Reply18918642 said:

You don't need X-point to do that: since Windows 95 and ATX, you can simply put your PC in Standby. I haven't had to reboot my PC more often than every couple of months for updates in ~20 years.18917236 said:Replacing RAM with a permanent storage would simply revolutionise computing. No more loading an OS, no more booting, no loading data

Remove your harddrive and let me know how that goes. The notion of "loading" is a concept of reading from your HD into your memory and initializing a program. So goodbye to all forms of "loading". -

hannibal The Main thing with this technology is that we can not afford it, untill Many years has passesd from the time it comes to market. But, yes, interesting product that can change Many things.Reply -

TerryLaze Reply

Sure you won't be able to afford a 3Tb+ drive in even 10 years,but a 128/256Gb one just for windows and a few games will be affordable if expensive even in a couple of years.18922543 said:10 years later... still unavailable/costs 10k

-

zodiacfml I dont understand the need to make it work as DRAM replaement. It doesnt have to. A system might only need a small amount RAm then a large 3D xpoint pool.Reply

The bottleneck is thr interface. There is no faster interface available except DIMM. We use the DIMM interface but make it appear as storage to the OS. Simple.

It will require a new chipset and board though where Intel has the control. We should see two DIMM groups next to each other, they differ mechanically but the same pin count.