China's latest round of rare-earth export controls gives the country dominion over precious resources — regulations have far-reaching implications for the semiconductor industry

Export controls expand to knowledge, tools and equipment

Last week, a new round of the U.S.-China trade war commenced. China imposed export controls on a new set of rare earth materials and the methods of their processing, which may impact a variety of products and industries. More importantly, China expanded its export control framework beyond raw materials, now reaching actual products and complex devices made outside of China. This means that a product produced anywhere in the world, but containing rare earth materials from China, may be subject to Beijing's export licensing regime if the value of rare earth materials in this product exceeds 0.1%. The U.S. was quick to retaliate with a 100% tariff on China-made products and a ban on 'critical software' for China-based entities.

Materials

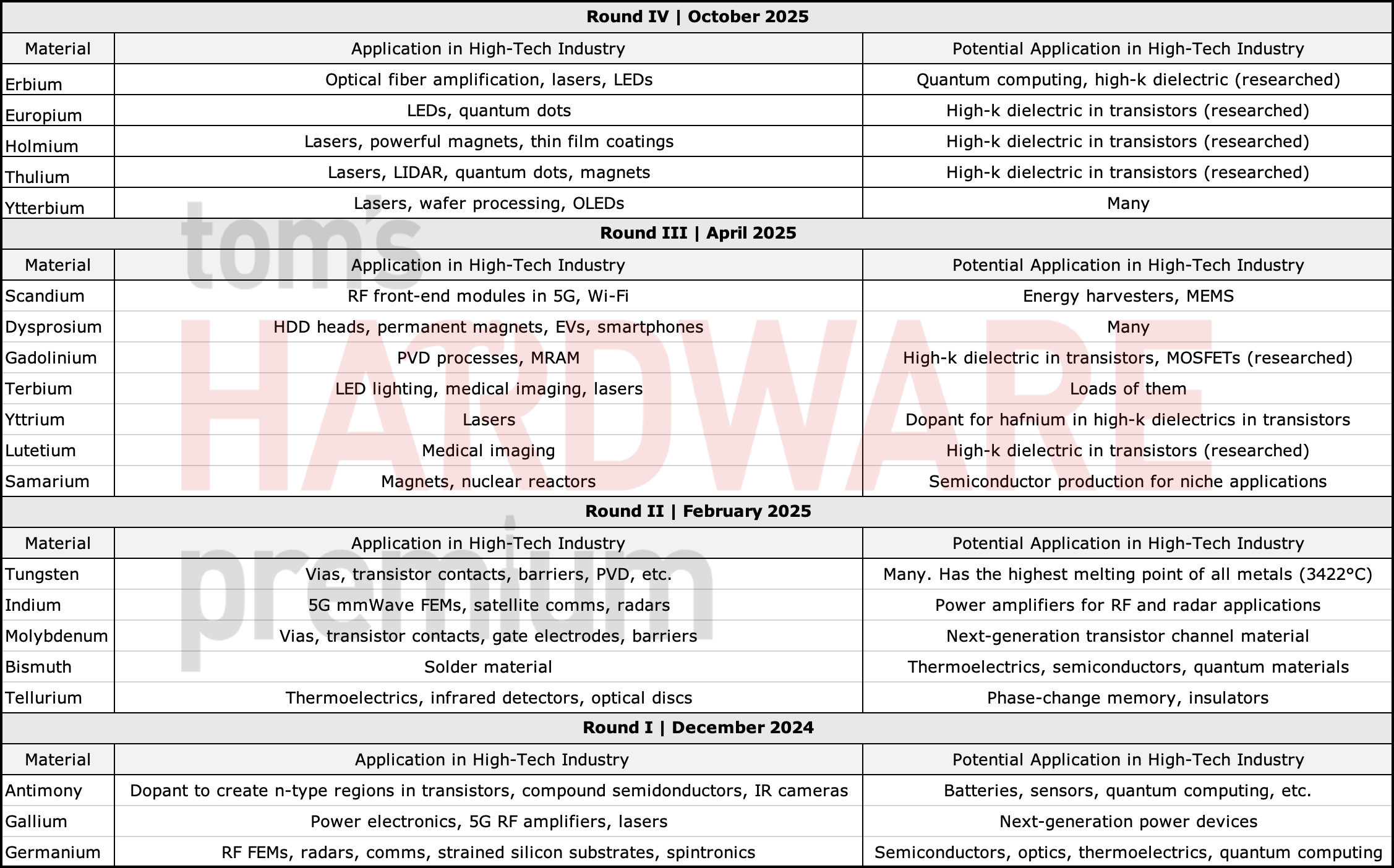

Starting early November, China will add five heavy rare-earth elements to its export controls list, including erbium, europium, holmium, thulium, and ytterbium, as well as their alloys, oxides, compounds, and finished materials.

The controls explicitly cover magnetic powders, luminescent phosphors, fibre-optic materials, thermal-shield coatings, hydrogen storage, and magnetic alloys. These five elements and alloys on their base are used to build devices like displays, EV drivetrains, lasers, magnetic subsystems (hard drives), optical and photonic infrastructure, satellites, and more.

This round of China's export controls targets rare earth elements that generate, manipulate, and sense light or magnetism, which are critically important for dozens of devices and industries. By tightening export controls over these materials, China is increasing its influence over both the supply of rare earths and the foundational building blocks that the computing, defence, and telecommunication industries rely upon worldwide.

While companies in these industries have the flexibility to switch from one supplier to another, doing so is difficult and expensive because they have downstream partners that need to validate and qualify all the components they use.

China's export controls policy evolved from restricting fundamental semiconductor materials such as antimony, gallium, and germanium (Round I) to advanced interconnect metals (Round II), then to functional rare earths used in chipmaking, telco, and storage devices (Round III, scandium and dysprosium).

The October 2025 round extends this logic to the optical and magnetic layer of the value chain, covering materials that enable fiber-optic networks, display manufacturing, laser, and EV motors. This is clearly not an isolated move, but is a part of a multi-stage plan that now spans every level of the electronics and semiconductor ecosystem from wafer substrates to photonics and magnetics.

The fourth round of rare earths export controls expands the list of materials that will now require a dual-use export license from China's Ministry of Commerce. While this hurts several industries, it does not hurt them significantly more than the prior rounds (particularly the April 2025 round), so we could consider the new list as an expansion of the Round III rather than an all-new Round IV (more on this later), though for simplicity we will call it this way.

The big question is whether the industry outside of China can replace the People's Republic's rare earth supplies in a timely manner. While there have been conversations about replacing China-originated materials, from semiconductor production and broader industries, the main limitation seems to be the lack of efficient technologies for processing rare earth elements.

Processing tools and methods

Over recent decades, China has not only perfected the mining of rare earth minerals but also the technologies required for the associated tools and processing. Therefore, companies and countries planning to switch from using materials from China to their own will have to buy equipment and technologies from Chinese companies. China's government now has everything covered.

The newly imposed export regulations now also include rare-earth production and processing equipment, covering over 20 types of industrial machinery. This includes centrifugal extraction units, acid-resistant roasting kilns, precipitation and crystallization reactors, electrolytic and vacuum furnaces, vacuum casting and sintering systems, isostatic and magnetic presses, laser and grinding machines, and crystal-growth furnaces used for high-purity rare-earth crystals.

Advanced crystal-growth furnaces are particularly important for antimony, gallium, germanium, and other rare-earth elements used in semiconductor manufacturing, though the exact purity levels and applications vary. High-purity materials are essential to minimize defects and ensure the consistent electrical properties demanded by process technologies. While it is theoretically possible to use different crystallization reactors, presses, and furnaces, the final material, although pure, will differ from that produced using standard tools.

This may require requalification of the semiconductor process technology, which might take months and incur significant costs. To that end, it will become difficult for foreign companies to mine and refine rare earth materials outside of China with the new regulation.

In addition, a new regulation introduced last week extends the same legal framework to the mining reagents, separation chemicals, and mineral feedstock required to produce or refine rare earths. Until now, China has mainly regulated exports of refined metals and oxides, while mining reagents and separation chemicals have been lightly monitored.

By adding these materials to the list of controlled items, China is closing an option for companies to buy Chinese reagents or ores and perform refining elsewhere. This means even if a foreign refinery exists, it cannot legally operate without a Chinese export license, which further reinforces China's control not just over mined output but over the mining and refining hardware, consumables, and chemical know-how.

Going beyond its own borders

The new export restrictions on five rare earth elements, mining and refining tools, and chemicals used for their mining and refining, clearly expand China's control over rare earth supplies and solidify the country's market share, the final set of restrictions is absolutely unprecedented as they expand export controls beyond China's borders.

Starting December 1, China will require foreign companies to obtain a dual-use Chinese export license if their products contain Chinese-origin rare-earth materials (≥ 0.1 % by value) or were manufactured using Chinese rare-earth mining, refining, or magnet-production technologies. The rule applies to all companies, regardless of geography.

The regulation outright prohibits exports to military users, to entities listed on China's export control or watch lists (and to their subsidiaries with 50% or more ownership), for end uses involving weapons of mass destruction, and terrorism, which is something to be expected.

However, the most painful part is that China's Ministry of Commerce will review export license applications related to the production or research of advanced logic (14nm and below), or 3D NAND (256-layer+ memory chips), as well as AI technologies with potential military applications. This means that China's ministry may refuse to supply materials to any chipmaker in the world, whether it is TSMC producing AI processors for Nvidia, or Micron producing 3D NAND memory for its latest SSD.

What's next?

From a strategic point of view, Round IV of China's rare earth materials export restrictions marks China's shift from being the world's largest supplier of rare earths to the global watchdog over rare earth materials and products. In addition to restricting shipments of 20 metals from China, the country now controls exports of processing equipment and chemicals. The country will also govern how rare earth materials and China's mining and refining knowledge are used worldwide. As a result, Beijing has gotten a set of powerful instruments of industrial and geopolitical control.

China's latest announcement may not be the last blow to the global semiconductor trade. However, further export controls won't have as much of an impact as the announced proposals on rare earth materials.

China already controls exports of foundational materials like antimony, gallium, germanium, as well as crucially important bismuth, indium, molybdenum, and tungsten. The country can expand the list of controlled elements further, albeit not very significantly.

Furthermore, now that China intends to control the means of rare earth mining and refining, as well as applications that use rare earth metals, the next step could be controlling the particular end user of finished products, just like the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Industry and Security controls end users of products made using American technologies.

This will require a global tracing system to identify Chinese rare-earth content across the supply chain, but the ongoing feud between China and the U.S. has demonstrated that both countries are willing to go great lengths to protect national interests.

Anton Shilov is a contributing writer at Tom’s Hardware. Over the past couple of decades, he has covered everything from CPUs and GPUs to supercomputers and from modern process technologies and latest fab tools to high-tech industry trends.